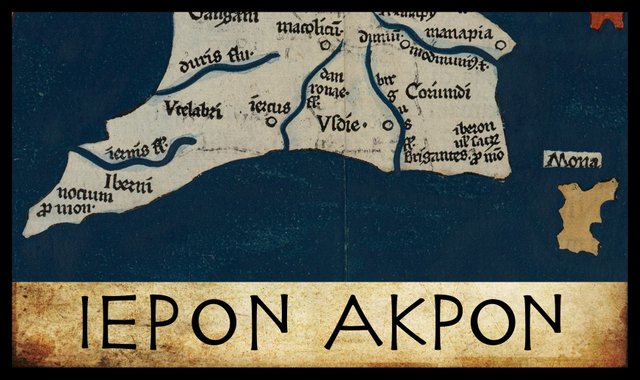

Ιερον Ακρον

Claudius Ptolemy’s description of Ireland in his Geography comprises a list of sixty items, forty of which are accompanied by latitudes and longitudes. In this article, I begin my study of these items in an attempt to identify them one by one. I am setting out from the south-east corner of the island and proceeding counterclockwise, before moving inland. Traders and explorers coming to Ireland from the continent or from southern Britain would probably have made their first landfall somewhere along this stretch of coast, and they were more likely to have explored the eastern side of the island before venturing west into the Atlantic Ocean.

Sacrum Promontorium

There is another reason for beginning in the south-east corner of the island: the promontory or headland which Ptolemy places at this point is one of the least controversial items in his list. Throughout the ages, scholars have been almost unanimous in identifying Ptolemy’s ἱερον ἀκρον with Carnsore Point in the south-east corner of Ireland. The only controversy has concerned the meaning and origin of the name—of which more later.

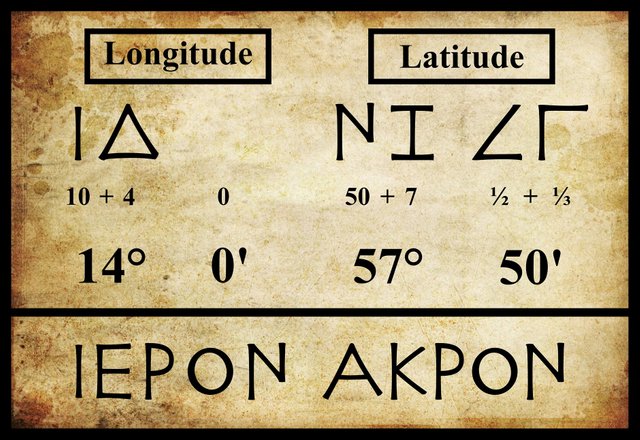

The principal sources are all in agreement in locating this landmark in longitude 14°, but there is a discrepancy of 20' of arc in the latitude. Müller (57° 50') follows the Vat Gr 191 manuscript, which is thought to be closest to Ptolemy’s lost autograph, while Wilberg and Nobbe (57° 30') follow most of the other sources. At least one manuscript places this promontory in latitude 58° (Orpen 120).

Ptolemy is believed to have indicated 30' of arc, or half a degree, with the symbol , or something like it, which signified one half. To indicate 50' of arc, he added to this the letter Γ (gamma). Gamma normally represented the number 3, but in this context it stood for the fraction 1/3. 50' is one half of a degree plus one third of a degree. It is possible that Ptolemy’s gamma was simply omitted by an early copyist, corrupting 50' to 30'. This is more likely than the addition of a extraneous gamma that was not in Ptolemy’s autograph. In several manuscripts, the previous item in Ptolemy’s list has a latitude of 57° 30'.

| Source | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|

| Müller | 57° 50' | 14° 00' |

| Wilberg | 57° 30' | 14° 00' |

| Nobbe | 57° 30' | 14° 00' |

| Vaticanus graecus 191 | 57° 50' | 14° 00' |

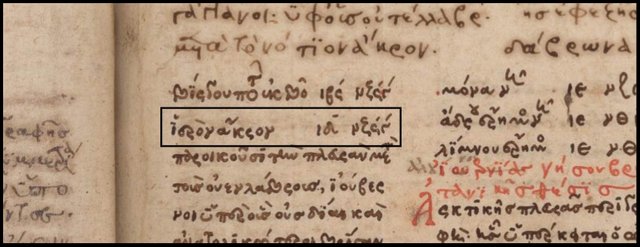

The name of the headland is also not in doubt. All extant manuscripts record it as ἱερὸν ἄκρον (Hieron Akron), with only minor diacritical differences between them. Ptolemy’s use of diacritics is unknown. The practice of adding primes to letters to indicate, for example, that they represent fractions rather than the usual integers was only regularized much later. In a recent study, Alexander Jones simply omits them:

I omit diacritical marks distinguishing whole numbers from fractions, since in my experience the testimony of manuscripts is practically worthless with respect to them. (Jones 42 n 27)

Alexander Jones is currently Professor of the History of the Exact Sciences in Antiquity for the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University.

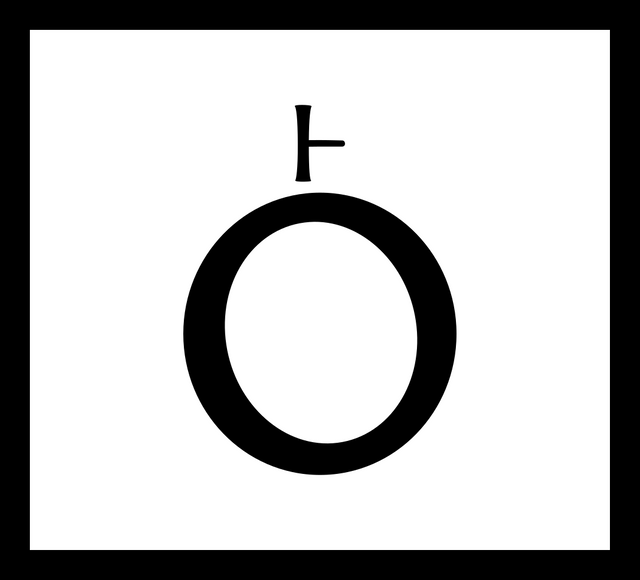

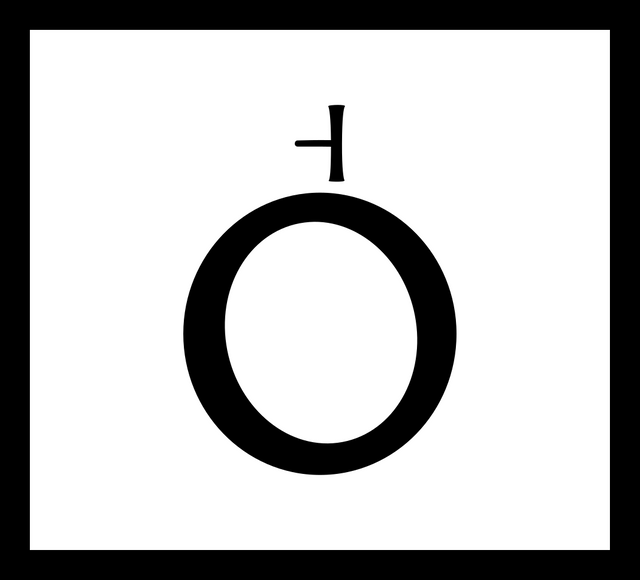

Amalia Gnanadesikan is the Technical Director for Language Analysis at the University of Maryland’s Center for Advanced Study of Language. In her book The Writing Revolution, she makes the following pertinent comment on the question of smooth and rough breathing in Ptolemy’s Alexandria:

In the process of accumulating and copying texts, the Alexandrian scholars began to show concern for matters of orthography. They found that at certain points the lack of a written form of [h] made for ambiguity. They noted that the Greeks living in Italy had been more free-thinking than the Athenians. While they had gone along with the adoption of the Ionic alphabet, they continued to write [h] by cutting the hēta in half and using ├. The Alexandrians adopted the Italian Greeks’ half H, but wrote it as a superscript on the following vowel, so that, for example,

was ho. Loving symmetry, they made the other half of H stand for the lack of an [h] sound before a vowel:

These diacritics came to be termed “rough breathing” (for [h]) and “smooth breathing” (for lack of [h]). Their use was for many centuries largely reserved for cases where ambiguity could arise without them. These marks later became ‘ and ’, so that ὁ was ho and ὀ plain o ... Only by the ninth century AD (well into the Byzantine period, AD 330–1453) did the use of breathing and accent diacritics become fully regular, with all vowel-initial words marked for “rough” or “smooth” breathing and all words marked for accent. (Gnanadesikan 220 ... 221)

I take these remarks to imply that Ptolemy probably only employed the diacritics for smooth and rough breathings in cases where the correct reading was not already obvious to the reader. This is the practice I intend to follow in this and subsequent articles.

Hieron Akron

The literal translation of this Greek name is Sacred Headland, or Holy Head, which appears in Latin editions of the Geography as Sacrum Promontorium. As it is wholly Greek, I chose to omit the breathings. The origin of this name, however, is anything but Greek. It was explained succinctly by O’Rahilly thus:

The name ’Ιέρνη, “Ireland”, had probably been picked up by the Massaliot Greeks, from merchants and from their Celtic neighbours, as early as the fifth century B.C. ... Compare gens Hiernorum in Avienus, implying ’Ιέρνοι in his Greek original. Owing to the loss of so much of the work of the early Greek geographers, ’Ιέρνη is not attested before Strabo (contemporary with Augustus). The digamma had disappeared from Ionic as early as the seventh century B.C.; and when the Massaliot Greeks first heard the name Īvernā [Ireland], they presumably had no means of indicating the -v- and simply dropped it. Later the Greeks adopted the expedient of representing v in foreign names by ου ... Ptolemy, or some near predecessor of his, modernized ’Ιέρνη into ’Ιουερνία ... (O’Rahilly 41-42. See also 83.)

So the original name of the south-eastern headland was Celtic and meant simply Cape Ireland, or Irish Head, or something of the sort. This was then corrupted to the Greek Holy Head. A similar corruption was also applied to the island as a whole by the Latin poet Avienus, as O’Rahilly again noted:

Avienus’s name for Ireland is sacra insula [Holy Isle] (Ora Maritima 108); presumably ’Ιέρνη νησος had been corrupted to ἱερὰ νησος in the Greek text he had before him. (O’Rahilly 83 fn 6)

Cape Ireland is an appropriate name for the first Irish landmark a foreign visitor would glimpse after crossing St George’s Channel.

Carnsore Point

Ireland’s south-eastern headland is now known as Carnsore Point, and there is little doubt that this is the headland Ptolemy is referring to. Curiously, though, scholars are not absolutely unanimous on this issue. Greenore Point, which lies 5 km northeast of Carnsore Point, and Hook Head, which lies about 20 km to the west of Carnsore Point in the same county—Wexford—have been favoured by a few:

| Carnsore Point | Greenore Point | Hook Head |

|---|---|---|

| - | - | Camden (1607) |

| Ware (1654) | - | - |

| - | - | Lewis (1837) |

| Orpen (1894) | - | - |

| - | Martin (1910) | Martin (1910) |

| Mac an Bhaird (1991-93) | - | - |

| Francis (1994) | - | - |

| Bursche & Warner (2000) | - | - |

| Darcy & Flynn (2008) | - | - |

Source: Darcy & Flynn 57

The modern name of Carnsore Point combines the Irish word carn with the old Norse eyrr. The latter signifies a small tongue of land running into the sea (Walsh 28), or a gravel beach. The former refers to a cairn or megalithic tomb. There was once such a structure close to the headland, known locally as the Giant’s Grave. In the Short Chronology, this was a Celtic artifact and probably postdated Ptolemy’s principal source. The following description of this structure is adapted from the National Monuments Service’s Historic Inventory Viewer:

Located at the bottom of a slight south- and east-facing slope at Carnsore Point, and marked on the 1839 and 1940 editions of the Ordnance Survey 6-inch map, where it is described in gothic lettering as a Giant’s Grave and a Dolmen respectively. The earliest reference is from the Dublin Magazine of August 1764, where it is described as 23ft [7 m] in length. The artist Gabriel Beranger sketched it in 1780 (Wilde 129), although this has never been published. The area was excavated (E000142) in 1975, but a trench (20m x 5m) produced no evidence of the structure. It can be concluded that erosion by the sea has removed all trace of it (Cahill and Lynch 7, 59).

The excavation in 1975 was carried out by Michael J O’Kelly on behalf of the Electricity Supply Board, which owned the surrounding land. A plan to construct a nuclear power plant on the site was famously thwarted by public protests in 1978. In 2003 a wind farm was opened on the site.

References

- Alexander Jones (editor), Ptolemy in Perspective: Use and Criticism of his Work from Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century, Springer, Dordrecht (2010)

- Amalia E Gnanadesikan, The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester (2009)

- Michael J O’Kelly, Archaeological Survey and Excavation of St. Vogue’s Church,

Enclosure and Other Monuments at Carnsore, Co. Wexford, Electricity Supply Board, Dublin (1975) - Lady Wilde, _ Memoir of Gabriel Beranger, and His Labours in the Cause of Irish Art, Literature, and Antiquities from 1760 to 1780, with Illustrations_, Journal of the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland, Fourth Series, Volume 4, Number 28, pp 111-56, Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Dublin (1876-78)

- M Cahill & A Lynch, The Excavation of St. Vogue’s Well and Dolmen (Site of) at Carnsore, Co. Wexford, *Journal of the Wexford Historical Society, Journal 6, pp 55-60, Wexford (1976)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- A Walsh, Scandinavian Relations with Ireland during the Viking Period, The Talbot Press Limited, Dublin (1922)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Part of Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Carnsore Point from the Air: Geograph Ireland, © Graham Horn, Creative Commons License

- Hieron Akron in Vat Gr 191, Folium 139r : Vat Gr 191, © Vatican Library, Fair Use

- On Carnsore Point: Geograph Ireland, © Alex Passmore, Creative Commons License

- Carnsore Point Wind Farm: Geograph Ireland, © Bob Embleton, Creative Commons License

You received a 10.0% upvote since you are not yet a member of geopolis and wrote in the category of "archaeology".

To read more about us and what we do, click here.

https://steemit.com/geopolis/@geopolis/geopolis-the-community-for-global-sciences-update-4

thanks dear for nice article.

@upvote done

educative post..thanks dear @harlotscurse

very important and learning post dear...i can learn from this. Thank u so much

like your article dear.

@upvote done

thats informative post, dear

@upvote done

so much informative.. you are good learner..

thank u so much..

@upvote done

awesome post,very nice story,

my dear friend @harlotscurse,

i love your post, you are good learner..

thank you for sharing with us,

wow.. looks great.... good to know about it....

amazing and eduvative post.