Does Jurassic Park make scientific sense?

In 1993, Steven Spielberg's film Jurassic Park defined dinosaurs for an entire generation.

It has been credited with inspiring a new era of palaeontology research.

But how much science was built into Jurassic Park, and do we now know more about its dinosaurs?

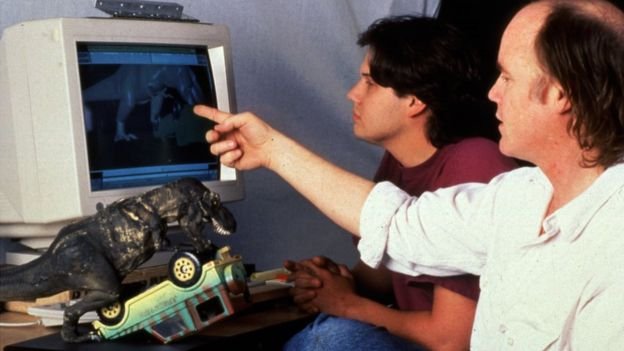

As its 25th anniversary approaches, visual effects specialist Phil Tippett and palaeontologist Steve Brusatte look back at the making of the film, and what we've learned since.

So, first of all, what did Jurassic Park get wrong? It started off by inheriting some complications from Michael Crichton's novel, on which the film was based.

"I guess Cretaceous Park never had that same ring to it," laughs Brusatte.

"Most of the dinosaurs are Cretaceous in age, that's true."

The Cretaceous period, which followed on from the Jurassic, was home to many of the dinosaurs which feature heavily in the film, including Tyrannosaurus rex, Velociraptor and Triceratops.

The idea of recreating dinosaurs from preserved DNA also proves problematic.

"In order to clone a dinosaur you would need the whole genome, and nobody's ever even found a little bit of dinosaur DNA," says Brusatte. "So we're talking about something that's pretty difficult, if not impossible."

Quibbling about such details may seem inconsequential. But for a film that proudly treats its prehistoric cast of creatures as characters rather than monsters, Jurassic Park treads a fine line between scientific accuracy and cinematic fantasy.

How to build a dinosaur

Case in point - building an animal that no human being has ever seen, and making it as realistic as possible.

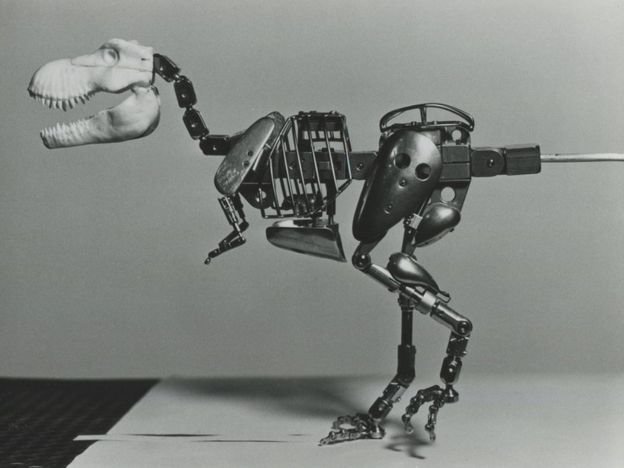

At the time, Jurassic Park was groundbreaking in its use of computer animation in tandem with animatronics.

Stop motion expert Phil Tippett, who had previously worked on Star Wars, was brought in as dinosaur supervisor, a role which would later earn him fame as an internet meme.

To the question in your title, my Magic 8-Ball says:

Hi! I'm a bot, and this answer was posted automatically. Check this post out for more information.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-44293060