Dispatches #170: Moral injuries, train drivers and pain empires

Thursday, 16 November 2017

Welcome to Dispatches, a weekly summary of my writing, listening and reading habits. I'm Andrew McMillen, a freelance journalist and author based in Brisbane, Australia. Apologies for missing the last two weeks; I was travelling, as you'll see in the lead item under 'Sounds' below.Words:

I had a story published in The Weekend Australian Magazine on Saturday. Excerpt below.

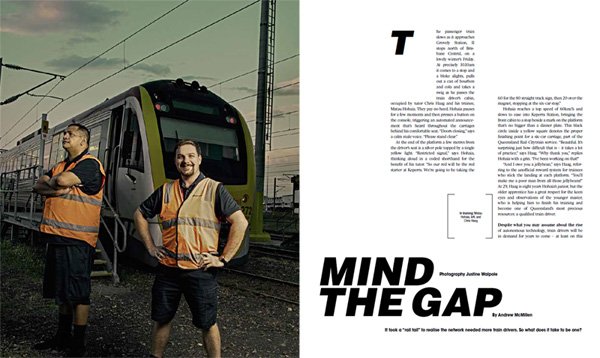

To read the full story, visit The Australian. Above photo credit: Justine Walpole.Mind The Gap (2,300 words / 12 minutes)

It took a "rail fail" to realise the network needed more train drivers. So what does it take to be one?

The passenger train slows as it approaches Grovely Station, 11 stops north of Brisbane Central, on a lovely winter's Friday. At precisely 10.10am it comes to a stop and a bloke alights, pulls out a can of bourbon and cola and takes a swig as he passes the train driver's cabin, occupied by tutor Chris Haag and his trainee, Matau Hohaia. They pay no heed. Hohaia pauses for a few moments and then presses a button on the console, triggering an automated announcement that's heard throughout the carriages behind his comfortable seat. "Doors closing," says a calm male voice. "Please stand clear."

At the end of the platform a few metres from the driver's seat is a silver pole topped by a single yellow light. "Restricted signal," says Hohaia, thinking aloud in a coded shorthand for the benefit of his tutor. "So our red will be the red starter at Keperra. We're going to be taking the 60 for the 80 straight track sign, then 20 over the magnet, stopping at the six-car stop."

Hohaia reaches a top speed of 60km/h and slows to ease into Keperra Station, bringing the front cabin to a stop beside a mark on the platform that's no bigger than a dinner plate. This black circle inside a yellow square denotes the proper finishing point for a six-car carriage, part of the Queensland Rail Citytrain service. "Beautiful. It's surprising just how difficult that is – it takes a lot of practice," says Haag. "Why thank you," replies Hohaia with a grin. "I've been working on that!"

"And I owe you a jelly bean," says Haag, referring to the unofficial reward system for trainees who stick the landing at each platform. "You'll make me a poor man from all those jelly beans!" At 29, Haag is eight years Hohaia's junior, but the older apprentice has a great respect for the keen eyes and observations of the younger master, who is helping him to finish his training and become one of Queensland's most precious resources: a qualified train driver.

How I found this story: In the wake of the widely publicised Queensland Rail network failure last year, I wanted to learn more about what it takes to become a qualified train driver, as frankly, I had no idea. I first contacted QR on October 31 2016 with a request to write a magazine story on this subject. Just over a year later, that story was published, making this perhaps the longest gestation period that I've yet experienced for a single magazine story.

It wasn't until June this year that I was out on the rails, sitting (or standing) in drivers' cabins, and having some memorable conversations at the business end of passenger trains. As you might expect, I gathered far more material than appears in the published story, but I'm happy with how this one turned out. I now have a lot of respect for the men and women who devote their lives to driving a million people per week – in south-east Queensland, at least – from signal to signal. Hopefully after reading this, you will, too.

Sounds:

Fireside chat with Steemit CEO Ned Scott at Steemfest 2017 (~60 minutes). Earlier this month, I was in Portugal for Steemfest, the second annual conference for cryptocurrency enthusiasts who are members of a social network called Steemit. I recently wrote about Steemit for Backchannel (in a story called The Social Network Doling Out Millions in Ephemeral Money) and as a result, I was invited to attend Steemfest and interview CEO Ned Scott to close the second day of the event.

Our "fireside chat" – accompanied by a beautifully warming YouTube clip of a fireplace – went for about an hour, and included a mix of questions from myself and the audience. My full conversation with Ned can be viewed via the YouTube live stream by clicking the above image. I'll be writing more about cryptocurrency in the coming months. (Above photo credit: @andrarchy)

Dirty John (six episodes, ~5 hours). While travelling to and from Portugal, I had plenty of time to absorb plenty of podcasts, and I was pleased to have the luxury of listening to this series in a single day. It's one of the better 'true crime' podcasts I've heard, though that moniker doesn't quite do it justice. The less you know or read about this one before beginning, the better. After listening, I also recommend this interview on The Sunday Long Read Podcast with the journalist who reported this story, Christopher Goffard from the L.A. Times.

Hugh Riminton on Conversations with Richard Fidler (~2 hours). A fascinating two-part conversation with journalist Hugh Riminton, who has just published a book about his life. I was particularly engaged by their discussions on the concept of 'moral injury' that is sometimes experienced by foreign correspondents, who see some of the worst parts of human nature and can become damaged as a result. Part two here.Debra Newell is a successful interior designer. She meets John Meehan, a handsome man who seems to check all the boxes: attentive, available, just back from a year in Iraq with Doctors Without Borders. But her family doesn't like John, and they get entangled in an increasingly complex web of love, deception, forgiveness, denial, and ultimately, survival. Reported and hosted by Christopher Goffard from the L.A. Times.

Jim Nelson on Longform (62 minutes). An absolute must-hear for magazine journalists, or those who aspire to that role. Jim Nelson has been in the editor's chair at GQ for nearly 15 years, and his enthusiasm for longform storytelling is almost palpable throughout his conversation with Max Linsky.Hugh has been a trusted figure on Australian television screens for decades, reporting from more than 40 countries. As a correspondent for the 9 Network, and then for CNN, he's brought many of the world's historic events to our screens, often reporting from the scene. In recent years, Hugh has been based in Australia, presenting and reporting for Network 10's Eyewitness News. A lifetime of journalism was never a forgone conclusion for Hugh. As a teenager growing up in New Zealand he was sideswiped by catastrophic depression and anxiety. His hopelessness was such that he was self-medicating with alcohol at the age of 15. But when Hugh landed a junior job in a newsroom, almost by accident, it was a stroke of fortune which he says probably saved his life.

129 Cars on This American Life (76 minutes). What a pleasure it is to revisit one of my favourite This American Life episodes, which was recently rebroadcast. The locale is a car dealership, and across several weeks, reporters spend substantial time with the car sales team as they endeavour to meet their goal of selling 129 cars in a calendar month. It's a fucking masterpiece of storytelling, with plenty of colourful characters, funny lines and dramatic tension. It's also a testament to my favourite type of journalism, which demands plenty of hanging around and waiting for things to happen. Do listen.Jim Nelson is the editor-in-chief of GQ. "One of the things that was initially a challenge was we would all think of 'the print side' and 'the digital side.' Now what we all think about is, 'Okay, stop saying GQ.com and GQ the print edition. It's just GQ!' And once you cross that line, you don't ever want to go back to it. I can't imagine. The job has changed so much, even in the last three years, that when I look back, I think, 'God, I was just such a quaint little fucker.'"

New Money on StartUp (28 minutes). This episode provides an excellent overview of the fairly new concept of Initial Coin Offerings by focusing on Kik's recent ICO, which raised nearly $100 million.We spend a month at a Jeep dealership on Long Island as they try to make their monthly sales goal: 129 cars. If they make it, they'll get a huge bonus from the manufacturer, possibly as high as $85,000 – enough to put them in the black for the month. If they don't make it, it'll be the second month in a row. So they pull out all the stops.

Waiting For The Punch on WTF with Marc Maron (96 minutes). I enjoyed this audio version of the first chapter from Maron's new book, which groups a couple of dozen guests all talking about their childhoods and upbringings.Kik, a chat app popular with teenagers, launched in 2010. Users flocked to it, and within a few years it was valued at a billion dollars. Then a new competitor came on the chat scene: Facebook. When Kik started struggling to grow their revenue and find new investors, they landed on a wild new idea. Now they're betting their company's future on creating their own cryptocurrency.

Marc presents a special audio version of the first chapter of Waiting for the Punch: Words to Live by from the WTF Podcast. This chapter features thirty WTF guests talking with Marc about growing up. Hear from Conan O'Brien, Sir Ian McKellen, Kevin Hart, Mel Brooks, RuPaul Charles, Jim Gaffigan, John Oliver, Maria Bamford, Paul Scheer, Norm Macdonald, Molly Shannon, John Darnielle, Ahmed Ahmed, Dave Attell, Russell Peters, Joe Mande, Ron Funches, Allie Brosh, Gillian Jacobs, The Amazing Johnathan, Jon Glaser, Amy Schumer, Wyatt Cenac, Aimee Mann, Tom Arnold, Bruce Springsteen, Leslie Jones, Terry Gross, Dan Harmon, and President Barack Obama.

Reads:

Driving Tomorrow by Tony Davis in The Australian Financial Review Magazine (5,200 words / 26 minutes). I loved this profile of Zoox CEO Tim Kentley-Klay, a former Australian animation studio head who began contemplating "what comes after the car" a few years ago, and has been quietly working away at that conundrum in Silicon Valley since. This excellent cover story contains Kentley-Klay's first media interviews about Zoox, which had been operating under a cloak of silence until this point, and it's fascinating to read about how his mind works. Highly recommended.

Empire of Pain by Patrick Radden Keefe in The New Yorker (12,900 words / 64 minutes). An extraordinary story about the Sackler family, whose ruthless marketing of the painkiller OxyContin has generated billions of dollars for the family business, Purdue Pharma, as well as millions of addicts. "There's going to be a jury somewhere, someplace, that's going to hit them with the largest judgment in the nation's history," predicts one of Patrick Radden Keefe's sources, in this exhaustively reported story.On December 8, 2014, Tim Kentley-Klay walked through the park-like gardens of a Silicon Valley venture capital firm known as DFJ, into a foyer filled with moon rocks, spacesuits and assorted parts of Apollo rockets. A folly of one of the partners, it is reputedly the largest private space collection in the United States and gives the place the slightly surreal feel of a sci-fi movie backlot. Melbourne-born Kentley-Klay had only recently arrived in "the Valley". He was on a tourist visa, moving between Airbnbs, and sneaking into a garage workspace at Stanford University without the right security pass. Now the 39-year-old was standing at one end of a long, tan coloured board table trying to convince a room full of hard-headed numbers people that he was going to change the world – and was going to do it in a field where he had no experience or qualifications whatsoever. DFJ is on Sand Hill Road, the mind-bogglingly expensive strip in Menlo Park where many of the world's largest venture capitalists have set up station. DFJ was one of the earliest investors in Twitter, Tumblr, and Elon Musk's SpaceX and Tesla businesses. It receives about 10,000 pitches a year but only a tiny fraction of hopefuls make it to the boardroom. Of those, maybe 25 eventually receive funding. Kentley-Klay's background could hardly have been less useful for his ambitions. He'd run a successful business, sure, but it was an animation studio back in Melbourne. His new venture, Zoox, had just four employees, one of whom he'd met playing poker at Melbourne's Crown Casino – and who also had no relevant experience. For the previous two years Kentley-Klay had "bootstrapped" Zoox. Now he wanted $US2.5 million seed capital to top up the $US1.3 million raised from Sydney's Blackbird Ventures and a few "angels". He brought with him Jesse Levinson, a 31-year-old Stanford postdoctoral researcher, who had been sufficiently taken with Kentley-Klay's ideas to throw in his lot with Zoox (and to lend the Melburnian a section of the garage where he worked). The pair projected onto the screen Tim's renderings of a "self-driving robot". It was an entirely symmetrical, electrically driven machine with no windscreen, mirrors or steering wheel. Its occupants faced each other in what he called "social seating". It steered at both ends and could move just as happily in either direction.

Up and Then Down by Nick Paumgarten in The New Yorker (7,800 words / 39 minutes). I greatly enjoyed revisiting this story from 2008, which I recall reading as a much younger writer, and being astounded that a magazine could devote so much time and space to a story about... the history of elevators. Still a marvel of reporting, and so many great lines, such as: "People tend to find it unnerving to ride in an elevator with no buttons; they feel as if they had been kidnapped by a Bond villain." I also love the detail about how, in most elevators built or installed since the early 1990s, the door-close button doesn't work. It's there mainly to make you think it works: "Once you know this, it can be illuminating to watch people compulsively press the door-close button. That the door eventually closes reinforces their belief in the button's power. It's a little like prayer." Goddamnit, what a great story.Humans have cultivated the opium poppy for five thousand years. The father of medicine, Hippocrates, recognized the therapeutic properties of the plant. But even in the ancient world people understood that the benevolent powers of this narcotic were offset by the perils of addiction. In his 1996 book, "Opium: A History," Martin Booth notes that, for the Romans, the poppy was a symbol of both sleep and death. During the nineteen-eighties, Raymond and Mortimer Sackler had a great success at Purdue with an innovative painkiller called MS Contin, a morphine pill with a patented "controlled release" formula: the drug dissolved gradually into the bloodstream over several hours. ("Contin" was short for "continuous.") MS Contin became the biggest seller in Purdue's history. But, by the late eighties, its patent was about to expire, and Purdue executives started looking for a drug to replace it. One executive who was centrally involved in this effort was Raymond's son Richard, an enigmatic, slightly awkward man who, in the family tradition, had trained as a doctor. Richard had joined Purdue in 1971 as an assistant to his father, and worked his way up. His name appears on numerous medical patents. In the summer of 1990, a Purdue scientist sent a memo to Richard and several other colleagues, pointing out that MS Contin could "face such serious generic competition that other controlled-release opioids must be considered." The memo described ongoing efforts to create a product containing oxycodone, an opioid that had been developed by German scientists in 1916.

Murky Waters by Cameron Stewart in The Weekend Australian Magazine (4,000 words / 20 minutes). A 24 year-old American singer was found dead in bed on a cruise ship near Darwin in 2013, yet her family are still waiting for answers, following what appears to be a botched police investigation into her death. Great reporting here by Cameron Stewart.The longest smoke break of Nicholas White's life began at around eleven o'clock on a Friday night in October, 1999. White, a thirty-four-year-old production manager at Business Week, working late on a special supplement, had just watched the Braves beat the Mets on a television in the office pantry. Now he wanted a cigarette. He told a colleague he'd be right back and, leaving behind his jacket, headed downstairs. The magazine's offices were on the forty-third floor of the McGraw-Hill Building, an unadorned tower added to Rockefeller Center in 1972. When White finished his cigarette, he returned to the lobby and, waved along by a janitor buffing the terrazzo floors, got into Car No. 30 and pressed the button marked 43. The car accelerated. It was an express elevator, with no stops below the thirty-ninth floor, and the building was deserted. But after a moment White felt a jolt. The lights went out and immediately flashed on again. And then the elevator stopped. The control panel made a beep, and White waited a moment, expecting a voice to offer information or instructions. None came. He pressed the intercom button, but there was no response. He hit it again, and then began pacing around the elevator. After a time, he pressed the emergency button, setting off an alarm bell, mounted on the roof of the elevator car, but he could tell that its range was limited. Still, he rang it a few more times and eventually pulled the button out, so that the alarm was continuous. Some time passed, although he was not sure how much, because he had no watch or cell phone. He occupied himself with thoughts of remaining calm and decided that he'd better not do anything drastic, because, whatever the malfunction, he thought it unwise to jostle the car, and because he wanted to be (as he thought, chuckling to himself) a model trapped employee. He hoped, once someone came to get him, to appear calm and collected. He did not want to be scolded for endangering himself or harming company property. Nor did he want to be caught smoking, should the doors suddenly open, so he didn't touch his cigarettes. He still had three, plus two Rolaids, which he worried might dehydrate him, so he left them alone. As the emergency bell rang and rang, he began to fear that it might somehow–electricity? friction? heat?–start a fire. Recently, there had been a small fire in the building, rendering the elevators unusable. The Business Week staff had walked down forty-three stories. He also began hearing unlikely oscillations in the ringing: aural hallucinations. Before long, he began to contemplate death.

Test Of Nerves by Sharon Bradley in Good Weekend (4,300 words / 22 minutes). A moving and well-written story about Good Weekend associate editor Sharon Bradley's experience of being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, which is on the rise among young women.Jackie Kastrinelis was excited about exploring her first Australian city so when her fellow crew members on the cruise ship Seven Seas Voyager threw a "beach party" to celebrate their arrival in Darwin the next day, the American dressed for the part. She donned her bathers, threw on white shorts and a white beach top and walked to the crew bar around 10pm to order a rum and Coke. It was the last costume change the 24-year-old cruise ship singer and entertainer would ever make. The Seven Seas Voyager was still 300km northeast of Darwin, a city she would never see. The next morning a crew member heard Jackie's alarm clock ringing in her cabin, number 3119. Jackie was found dead in bed, lying on her back. It was 10.25am on February 3, 2013. "[We] were told that she looked like an angel," fellow cast member Courtney Brady told Jackie's parents, Mike and Kathy Kastrinelis. More than four years on, the question of what, or who, killed the talented and seemingly healthy performer in the prime of her life remains unanswered. "We lost our child and now we have been put through this," Kathy says as she flicks through three giant folders of documents in their home in the small town of Groveland, Massachusetts. "All we want to know is what killed our daughter. It is unconscionable what they have put us through."

Telling Tales by Peter Craven in The Weekend Australian Review (3,100 words / 16 minutes). I loved this profile of author Helen Garner, which coincides with the publication of two new collections of her writing.It's funny how the memory snags on certain details. For some reason, I can remember exactly what I was wearing the day my life changed forever: a navy-blue wool dress, long black boots and a silver pendant that my husband, Andrew, had given me four weeks earlier for my birthday. It was July 3, 2015. We'd woken up to the news that Phil Walsh, coach of AFL's Adelaide Crows, had been found dead at his home, the victim of multiple stab wounds. His son had already been arrested. As we inched our way through morning rush-hour traffic for an appointment with my neurologist, it was the only news story on the radio. It felt like an omen. The Brain and Mind Research Institute in Sydney's Camperdown was almost deserted when we arrived. My neurologist, russet-haired and goateed, wore rimless glasses and an air of quiet authority. He showed us into to his office, where two chairs, sympathetically angled towards his desk, waited. On a shelf off to the right, I noticed, was a box of tissues. The stage was set, it seemed, for a serious talk. I'd recently finished a battery of tests – "We're going to throw the net wide," he'd promised me a month earlier – and I was here for the results. The good news, he said, looking at some papers in front of him and glancing over at us, was that no antibodies for Myasthenia gravis (a neuromuscular autoimmune disease) had been found in my blood work. A pause. He was also ruling out Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (or ALS, more commonly called Motor Neurone Disease). Andrew squeezed my hand as I looked down into my lap, exhaling. The possibility of this terrible assassin, with its strangulating, five-year death sentence, had kept us both wide-eyed, staring at the bedroom ceiling at 1am, for a couple of weeks now.

This Is Not An Opera House by Darryn King in The Monthly (4,300 words / 22 minutes). An excellent essay about the Sydney Opera House, which, despite its outward beauty, has never been a very good venue for hosting opera or theatre shows.There's something preposterous about Helen Garner being 75. The woman who became famous for Monkey Grip – the novel (was it?) about being with a junkie – and who a decade or so later produced that elegant novella The Children's Bach, which compelled the admiration of Raymond Carver, has for the longest time been writing riveting nonfiction focused in practice on courtroom dramas and controversies. They range from The First Stone, about the Ormond College affair, in which a master was accused of abusing the girls; then to Joe Cinque's Consolation, about the degree of responsibility a young woman might bear for killing her boyfriend; and more recently This House of Grief, about Robert Farquharson, found guilty of deliberately drowning his three children in his car. Garner has written a huge number of essays as well as several very distinguished stories. The book of nonfiction with the blue cover, True Stories, is immense; the red book, Stories, is slender. They meet in uncanny ways. Monkey Grip is a novel (and a powerful one) but Garner is also a prodigious diarist. She has read every word of Samuel Pepys, the most famous diarist in the language, and her recounting of the actual can seep into the nonfiction in disarming ways. The nonfiction –– whether it is about the forensics and debilities of high and terrible crimes or the behaviour of up-themselves boy waiters and dreadful girls –– also features a Garner who can be the object of deadly ironic perspectives, from a master of fictional technique who sits who knows where.

++When the actor John Malkovich appeared in The Giacomo Variations, a chamber-opera bio-play of Giacomo Casanova, at the Sydney Opera House in 2011, he wasn't exactly seduced by the venue. "It's lovely to drive by on a motor boat and it has a very nice crew and very capable, but the acoustics are hideous," he told the Daily Telegraph. "For a catholicity of reasons, it's not the wisest place to put on anything ... with the possible exception of maybe a circus." Malkovich's comments hit a sore point, not just for the Concert Hall, the Sydney Opera House's largest performance space, but also for the building as a whole. Since being dreamed up 60 years ago, the site has inspired breathless arias of adulation ("On a moonlit night," wrote Ruth Cracknell in her memoir, "one could die of excess"), countered by basso-profundo grumbles that its splendour is only as deep as its Sweden-sourced ceramic skin. Conductor Sir Simon Rattle complained that the sound in the Concert Hall lacked richness and clarity, and came "from all sides". Former Sydney Symphony Orchestra chief conductor Edo de Waart described the sound as "barren", "cold" and "not alive", and threatened to boycott the "ugly" venue. "[It's] like you're in a barn," he said. The same year as Casanova dropped in, the Concert Hall's conjoined smaller sibling, the Opera Theatre (since renamed the Joan Sutherland Theatre), was voted the worst of Australia's 20 major classical music venues in a Limelight magazine industry poll. (The Concert Hall itself came in 18th.) The Opera Theatre was inadequate for anything bigger than a Mozart opera buffa, said Scottish opera director David McVicar. Brian Thomson, a regular scenic designer for Opera Australia, has recommended that the whole building be gutted. Even Dame Joan likened the interior of the building to an airport terminal.

Thanks for reading. If you have feedback on Dispatches, I'd love to hear from you: just reply to this email. Please feel free to share this far and wide with fellow journalism, music, podcast and book lovers.

Andrew

--

E: [email protected]

W: http://andrewmcmillen.com/

T: @Andrew_McMillen

If you're reading this as a non-subscriber and you'd like to receive Dispatches in your inbox each week, sign up here. To view the archive of past Dispatches dating back to March 2014, head here.

yo @andrewmcmillen, I just saw your steemfest talk with ned and was wondering if you would like 5k SP delegation? I see that your voting power is at 100% using SteemNow which means you haven't been up-voting/curating much ... would 5k delegation motivate you?

Let me know and I'll surely send some love your way.

If you want to do that, sure, go ahead. As you've noticed, I'm not a heavy user of the site, but I try to check it most days.

Sent!

Depending on your engagement, you may have it indefinitely. Peace and congrats!

Thanks mate!

I think the biggest problem QR has is union interference. I remember reading or hearing that QR driver training takes 3 years compared to somewhere like Germany, which takes 6 months. I can't find anything to back this up though, but it sticks out in mind. It also sounds very much like something the unions would try to enforce to ensure driver scarcity and protect the financial benefits (penalty rates, overtime, etc.) accruing to the existing drivers.

Hi there, thanks for reading. QR driver training used to take 18 months, until it was recently reduced to about 13 months. Train driver recruitment was recently opened to the general public (ie outside existing QR employees) for the first time, too : http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-31/more-train-drivers-for-seq-after-union-overruled-by-fair-work/8860384

Excellent. That is good news.

Congratulations @andrewmcmillen! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP