TWO HUNDRED YEARS OF BLUE

With Carl Sagan’s poetic Pale Blue Dot on my mind lately, I have found myself dwelling on the color blue and the way our planet’s elemental hue, the most symphonic of the colors, recurs throughout our literature as something larger than a mere chromatic phenomenon — a symbol, a state of being, a foothold to the most lyrical and transcendent heights of the imagination.

Gathered here is a posy of blue from some of my favorite encounters with this more-than-color in the literature of the past two centuries.

![IMG_20180525_132017.png]

( )

)

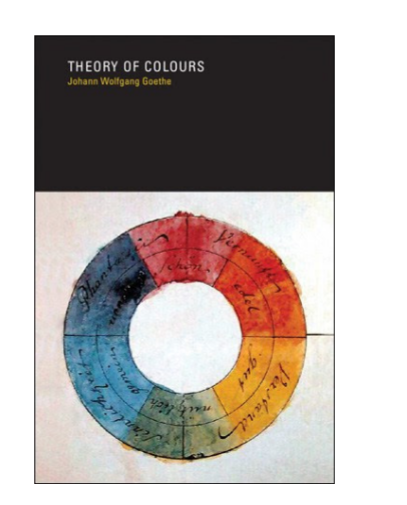

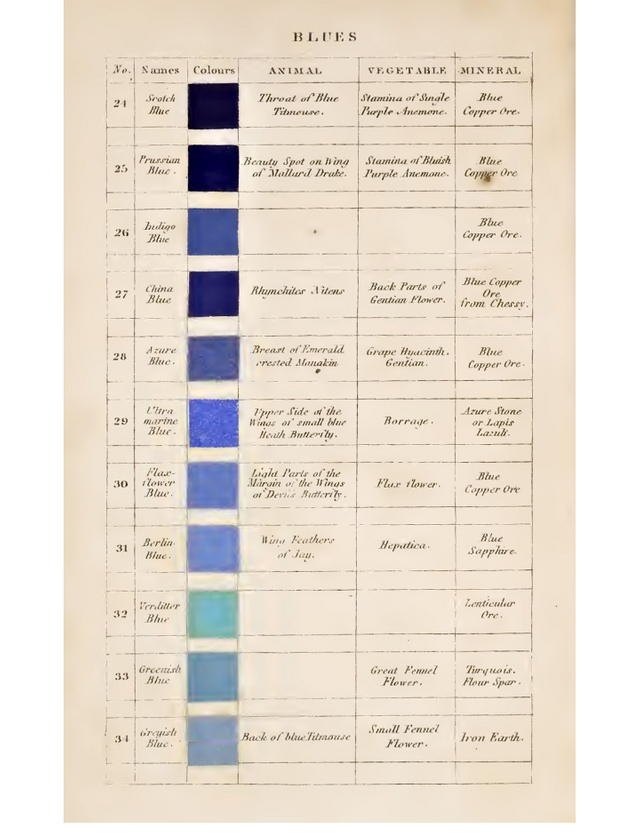

In his sixty-first year, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (August 28, 1749–March 22, 1832), by then Europe’s reigning intellect, published Theory of Colors (public library | public domain) — his effort to unearth the psychological link between color and emotion nearly a century before the dawn of psychology as a formal field of study, penned just before his compatriot Abraham Gottlob Werner released his seminal scientific nomenclature of color, which Darwin would later take on The Beagle.

“We love to contemplate blue,” Goethe wrote, “not because it advances to us, but because it draws us after it.” The treatise, composed as a refutation of Newton, turned out to have no scientific validity. But its conceptual aspects fascinated and inspired generations of philosophers and scientists ranging from Arthur Schopenhauer to Kurt Gödel.

Color chart by Patrick Syme for Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours: Adapted to Zoology, Botany, Chemistry, Mineralogy, Anatomy, and the Arts.

Goethe writes in the section allotted to blue:

As yellow is always accompanied with light, so it may be said that blue still brings a principle of darkness with it.

This color has a peculiar and almost indescribable effect on the eye. As a hue it is powerful — but it is on the negative side, and in its highest purity is, as it were, a stimulating negation. Its appearance, then, is a kind of contradiction between excitement and repose.

As the upper sky and distant mountains appear blue, so a blue surface seems to retire from us.

But as we readily follow an agreeable object that flies from us, so we love to contemplate blue — not because it advances to us, but because it draws us after it.

Blue gives us an impression of cold, and thus, again, reminds us of shade… Rooms which are hung with pure blue, appear in some degree larger, but at the same time empty and cold.

The appearance of objects seen through a blue glass is gloomy and melancholy.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU (1843)

“Where is my cyanometer,” Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817–May 6, 1862) exclaimed in his splendid journal on a blue-skied spring day, referring to the curious device invented by the Swiss scientist Horace-Bénédict de Saussure a century earlier to measure the blueness of the sky, which the polymathic naturalist Alexander von Humboldt enthusiastically embraced. “We love to see any part of the earth tinged with blue, cerulean, the color of the sky, the celestial color,” Thoreau wrote in another spring entry. “The blue of my eye sympathizes with this blue in the snow,” he recorded in a winter one. “Blue is light seen through a veil,” he wrote on the precipice of the two seasons.

Thoreau’s writings, dancing at the borderline between observation and contemplation, are strewn with his love of blue. Most often, he records his delight at the raw reality of the color as he encounters it in nature. Occasionally, however, he leaps from the actual into the abstract, drawing from physical blueness insight into the metaphysical dimensions of existence.

In a travelogue from an 1843 walk to Waschusett, found in his indispensable Excursions (free ebook | public library) — the source of his lovely meditation on finding spiritual warmth in winter — Thoreau writes:

We resolved to scale the blue wall which bound the western horizon… In the spaces of thought are the reaches of land and water, where men go and come. The landscape lies far and fair within, and the deepest thinker is the farthest travelled.

Peering into the blue horizon from the conquered mountain summit at the end of the journey, he finds in it a metaphor for the boundlessness of the human spirit:

We will remember within what walls we lie, and understand that this level life too has its summit, and why from the mountain-top the deepest valleys have a tinge of blue; that there is elevation in every hour, as no part of the earth is so low that the heavens may not be seen from, and we have only to stand on the summit of our hour to command an uninterrupted horizon.

WASSILY KANDINSKY (1910)

Exactly a century after Goethe, the great Russian painter and art theorist Wassily Kandinsky (December 16, 1866–December 13, 1944) examined the psychological and spiritual dimensions of art through the lens of form and color. In Concerning the Spiritual in Art (free ebook | public library), Kandinsky devotes an especially impassioned section to blue:

The power of profound meaning is found in blue, and first in its physical movements (1) of retreat from the spectator, (2) of turning in upon its own centre. The inclination of blue to depth is so strong that its inner appeal is stronger when its shade is deeper. Blue is the typical heavenly colour… The ultimate feeling it creates is one of rest… [Footnote:] Supernatural rest, not the earthly contentment of green. The way to the supernatural lies through the natural.

When it sinks almost to black, it echoes a grief that is hardly human… When it rises towards white, a movement little suited to it, its appeal to men grows weaker and more distant. In music a light blue is like a flute, a darker blue a cello; a still darker a thunderous double bass; and the darkest blue of all — an organ.

GEORGIA O’KEEFFE (1916)

There is a strange paucity of blue in the private writings of literature’s bluest soul. Virginia Woolf (January 25, 1882–March 28, 1941) rarely mentions the color throughout her journals, collected in A Writer’s Diary (public library) — the indispensable posthumous volume that gave us Woolf on the creative benefits of keeping a diary, the consolations of growing older, the relationship between loneliness and creativity, what makes love last, and her arresting account of a total solar eclipse.

But when she does turn to blue, it becomes more than a color, more than a mood — a subtle yet piercing hue of being, or rather the color of the lacuna between being and nonbeing. In an entry from April 9 of 1937, four springs before the blue of her lifelong depression and the River Ouse swallowed her, Woolf limns the singular blue of a particular interior space. Alluding to Wordsworth’s verse addressing “the heart that lives alone, housed in a dream,” she quotes another line and argues with the poet:

“Such happiness wherever it is known is to be pitied for tis surely blind.” Yes, but my happiness isn’t blind. That is the achievement, I was thinking between 3 and 4 this morning, of my 55 years. I lay awake so calm, so content, as if I’d stepped off the whirling world into a deep blue quiet space and there open eyed existed, beyond harm; armed against all that can happen. I have never had this feeling before in all my life; but I have had it several times since last summer: when I reached it, in my worst depression, as if I stepped out, throwing aside a cloak, lying in bed, looking at the stars, these nights at Monks House. Of course it ruffles, in the day, but there it is.

RACHEL CARSON (1941)

A quarter century before marine biologist and author Rachel Carson (May 27, 1907–April 14, 1964) catalyzed the modern environmental movement with her epoch-making book Silent Spring, she performed another unprecedented feat. In a lyrical essay about the underwater world — a world then more mysterious than the moon — she invited the human reader to experience the reality of life on this planet from the nonhuman perspective of marine creatures. Nothing like it had been done before. Published in The Atlantic, the essay became Carson’s first literary breakthrough and led to her 1941 book Under the Sea-Wind (public library) — a series of lyrical narratives about the life of the shore, the open sea, and the oceanic abyss.

In a passage about the migration and mating of eels, she bridges the scientific and the poetic to plunge the human imagination into the otherworldly blue of the deep sea:

The young eels first knew life in the transition zone between the surface sea and the abyss. A thousand feet of water lay above them, straining out the rays of the sun. Only the longest and strongest of the rays filtered down to the level where the eels drifted in the sea — a cold and sterile residue of blue and ultraviolet, shorn of all its warmth of reds and yellows and greens. For a twentieth part of the day the blackness was displaced by a strange light of a vivid and unearthly blue that came stealing down from above. But only the straight, long rays of the sun when it passed the zenith had power to dispel the blackness, and the deep sea’s hour of dawn light was merged in its hour of twilight. Quickly the blue light faded away, and the eels lived again in the long night that was only less black than the abyss, where the night had no end.

TONI MORRISON (1987

'' We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives,” Toni Morrison wrote in her spectacular acceptance speech as she became the first African American woman to win the Nobel Prize. The cornerstone for the trailblazing distinction was Morrison’s 1987 novel Beloved (public library), inspired by the true story of a woman’s escape from slavery and the unfathomable cost she had to pay for her freedom.

In a scene on the banks of the river, where the fugitive heroine gives birth to her baby daughter aided by the cover of night and the white woman with the kind hands, Morrison shines a sidewise gleam on the abiding question of destiny. She contemplates what fate may hold for this new life that had so closely escaped death before entering a pitiless world; what it may hold for any life. Morrison wrests from one of this planet’s rare blue plants an exquisite existential metaphor:

Spores of bluefern growing in the hollows along the riverbank float toward the water in silver-blue lines hard to see unless you are in or near them, lying right at the river’s edge when the sunshots are low and drained. Often they are mistook for insects — but they are seeds in which the whole generation sleeps confident of a future. And for a moment it is easy to believe each one has one — will become all of what is contained in the spore: will live out its days as planned. This moment of certainty lasts no longer than that; longer, perhaps, than the spore itself.

REBECCA SOLNIT (2005)

)

)

Rebecca Solnit examines the color blue and its relationship to desire in a stunning essay that may well be the crowning achievement of this chromatic category of literature, found in A Field Guide to Getting Lost (public library) — her sublime meditation on how we find ourselves in the unknown.

In an exquisite centrifugal unfolding from the scientific into the poetic, Solnit writes:

The world is blue at its edges and in its depths. This blue is the light that got lost. Light at the blue end of the spectrum does not travel the whole distance from the sun to us. It disperses among the molecules of the air, it scatters in water. Water is colorless, shallow water appears to be the color of whatever lies underneath it, but deep water is full of this scattered light, the purer the water the deeper the blue. The sky is blue for the same reason, but the blue at the horizon, the blue of land that seems to be dissolving into the sky, is a deeper, dreamier, melancholy blue, the blue at the farthest reaches of the places where you see for miles, the blue of distance. This light that does not touch us, does not travel the whole distance, the light that gets lost, gives us the beauty of the world, so much of which is in the color blue.

For many years, I have been moved by the blue at the far edge of what can be seen, that color of horizons, of remote mountain ranges, of anything far away. The color of that distance is the color of an emotion, the color of solitude and of desire, the color of there seen from here, the color of where you are not. And the color of where you can never go. For the blue is not in the place those miles away at the horizon, but in the atmospheric distance between you and the mountains. “Longing,” says the poet Robert Hass, “because desire is full of endless distances.” Blue is the color of longing for the distances you never arrive in, for the blue world.

This blue of distance and unmet longing, Solnit argues, is what makes desire so disquieting. We seek to silence it either by grasping toward its object in hungry hope of consummation or with the restless resistance of denial and suppression. We seem unable to befriend desire on its own terms and approach it with what John Keats memorably termed “negative capability.” Solnit offers a remedy for this chronic and self-defeating anxiety:

We treat desire as a problem to be solved, address what desire is for and focus on that something and how to acquire it rather than on the nature and the sensation of desire, though often it is the distance between us and the object of desire that fills the space in between with the blue of longing. I wonder sometimes whether with a slight adjustment of perspective it could be cherished as a sensation on its own terms, since it is as inherent to the human condition as blue is to distance? If you can look across the distance without wanting to close it up, if you can own your longing in the same way that you own the beauty of that blue that can never be possessed? For something of this longing will, like the blue of distance, only be relocated, not assuaged, by acquisition and arrival, just as the mountains cease to be blue when you arrive among them and the blue instead tints the next beyond. Somewhere in this is the mystery of why tragedies are more beautiful than comedies and why we take a huge pleasure in the sadness of certain songs and stories. Something is always far away.

After relaying the personal significance of blue in a vividly remembered childhood experience, Solnit closes an altogether extraordinary essay with a return to the universal coloring of distance and longing:

The blue of distance comes with time, with the discovery of melancholy, of loss, the texture of longing, of the complexity of the terrain we traverse, and with the years of travel. If sorrow and beauty are all tied up together, then perhaps maturity brings with it not … abstraction, but an aesthetic sense that partially redeems the losses time brings and finds beauty in the faraway.

[…]

Some things we have only as long as they remain lost, some things are not lost only so long as they are distant.

JANNA LEVIN (2006)

A Mad Man Dreams of Turing Machines (public library) by astrophysicist Janna Levin remains one of the most beautiful, profound, and intellectually elegant books I have ever read — a splendid biographical novel levitating with the poetics of a rapturous imagination, yet rigorously grounded in the real lives and scientific contributions of two of the twentieth century’s most tragic geniuses: computing pioneer Alan Turing and trailblazing mathematician Kurt Gödel.

The richest, most enchanting aspect of the book is the way it illuminates just how inseparable our so-called personal lives are from our public contribution — how Turing and Gödel’s singular lonelinesses and loves shaped their character, informing and inspiring the landmark breakthroughs we celebrate as their scientific genius. For Turing, the most formative fact of his life was his deep adoration of his boyhood classmate Christopher Morcom, with whom he fell in love at the boarding school where the teenage Alan was mercilessly bullied by the other boys, nearly to death. Christopher was everything Alan was not — dashing, polished, well versed in both science and art, aglow with charisma. Alan’s love was profound and pure and unrequited in the dimensions he most longed for, but Christopher did take to him with great warmth and became his most beloved, in fact his only, friend. They spent long nights discussing science and philosophy, trading astronomical acumen, and speculating about the laws of physics. For the remainder of his life, Turing would consider Morcom his soul mate.

It is an intense blue that Levin chooses as the backdrop of their improbable love. In a stunning scene suspended between science and romance — two realms of the human experience grounded in a shared longing to make the impossible possible — she writes:

Chris had shown him the reaction between solutions of iodates and sulfites. Holding the mixture in a clear beaker near his face, he watched Alan’s response as the solution turned a bold blue, tinting Christopher’s hair and deepening the hue of his eyes. To Alan it seemed the other way around, as though Chris’s beautiful eyes had stained the beaker blue.

[…]

He often tries to re-create the moment when Chris’s spirit seeped out of the portals of his eyes and infused the room, a stunning concentration of his soul trapped in the indigo liquid in the beaker. He knows the simple form of the chemicals and the rules of their combination, but he can’t shake the force of the impression that Chris makes on him. He can’t limit the experience to the confines of ordinary matter.

This is great content, but I was away from Steemit so long, I didn't see it in time to upvote it! I suggest you make another post that provides a link to this one, and I will gladly upvote and resteem that one!