What is it like talking to a 5 year old?

I went down to Gwangju for a week to rest, to get a break from the city life in Seoul. Although 70 percent of the Korean peninsula is already riddled with mountains, the four hour bus ride to suburbia still feels like a getaway.

But rest was not an option. The moment I arrived at the terminal, I was greeted by my two cousins surrounded by a circle of three toddlers running around their ankles. From the pleading look in their baggy eyes, it was clear that I was unofficially hired as a babysitter.

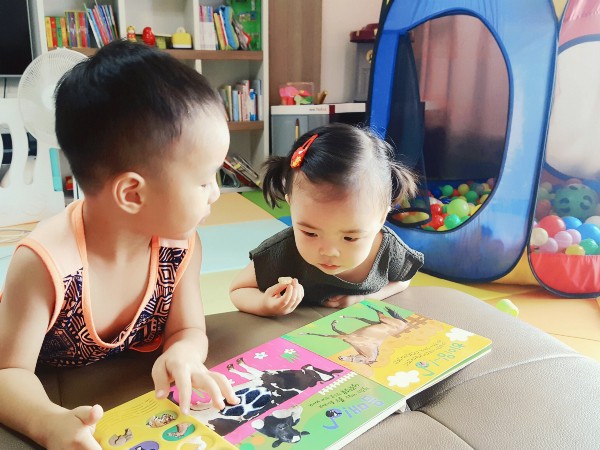

[5-year old and 2-year old]

My two nieces are only three and two years old, while the little boy is five. The nieces speak coherently, to a certain extent, but they are still far from reaching continuity when it comes to logic, argument, or their own emotions. They are easily distracted, and the longevity of their grudges or fits lasts two minutes maximum. However, the little boy, whose hobbies are largely Dinosauric — collecting figures of them, as well as, becoming them — can hold a fairly intelligible conversation and can retain emotional distress up to thirty minutes.

In the beginning, unused to the presence of children of such young age, I felt the awkwardness I usually feel around the species at the opposite end of the spectrum — senior citizens. But unlike the elderly who seem to be born wrinkled, slow, and boring, these children were a rapidly evolving species masquerading in insurmountable innocence that constantly placed me in positions of embarrassment, humility, and unwanted authority.

They felt, in other words, kind of threatening.

But as I got to know them during the week, I opened up to them rather quickly. This can be attributed to only one thing — The fact that they opened up to me almost immediately. All they needed was a name to call me by, one or two reasons to trust me, and that was that. We struck up a relationship that had no substantial basis, no judgment of talent or ability, no system of profit or trade.

It feels wrong to put into words what the week was like. Although they spoke in Korean, the interactions we had cannot actually be described in any existing language. Certainly they are at an age where they pick up signifiers rapidly, but the intended signified behind their signifiers exist on a whole different plane of meaning and logic that the signifiers are rendered moot in context.

This isn’t to say that they are not to be taken seriously. In fact, the degree of seriousness in their words and actions are unmatched in terms of proportional emotional damage. What seems trivial in our eyes must be placed in the context of their small physique, compressed life-world problems, and myopic perspective of time, which lacks past and future. If only the present matters, then the issue cannot wait, and it cannot be belittled by any issues prior.

[Hit me in the face and choked me to take a selfie]

My five-year-old nephew has the most difficult time falling asleep. This is because he is busy being Tyrannosaurus Rex. The king of the dinosaurs cannot just, like, sleep. It isn’t a king for slumbering eight hours a day. At night, his mother, father, and grandmother take turns trying out various methods to get him to sleep. They tell scary stories (which works, but only until he forgets), they all pretend to fall asleep with him (this is all happening around 10PM), they threaten him (rescinding previous promises of dessert), they beg him (which only encourages him to go against their wishes more), and finally, they just actually fall asleep, giving up. But only after they have heard him roar and stomp around the room or jump from bed to bed, pretending to fly like Pteranodon.

On my last night in Gwangju, I was sleeping in the same room with my aunt (his grandmother) and him. The lights were off at ten, but he was too hyper to fall asleep, let alone sit still for five seconds. My aunt, frustrated, but trying to hide her anger, went under her covers, and decided that she might as well fall asleep herself and leave it to me to watch whether he falls off the bed or not. Me, inheritor of the most difficult duty, felt a generosity that only comes with sufficient amount of distance. I knew this would be my last chance to be annoyed by this little kid, and my last chance to see him as a five-year-old, since I wasn’t sure when I would come back in the year.

“Hey, do you want to hear a dinosaur story?” This was my line to convince my nephew to cuddle up next to me in the bed. He leapt in the dark in excitement and pushed right up against my side, even pushing down my left breast hard in the process, which really hurt, but he was five, with a vague sense of the female anatomy.

Although my idea had been brilliant to get him to lie down, the difficult part was the storytelling itself. When was the last time I had even spoken the word ‘dinosaur’? I didn’t know any stories. I knew that the long necked one was a vegetarian, and the king was the short front-legged T-Rex. But I was not aware of any interesting narrative involving these Triassic creatures.

So, I went for trivia.

Me: Do you know what brachiosaurus eats?

Him: It’s an herbivore!

Me: Yes. That’s correct. Do you know what tyrannosaurus rex eats?

Him: MEAT.

Me: Yeah! Do you know what pterodactyl eats?

Him: It swoops in over the water and eats fish.

Me: Yes. Very good. -pause-

Me: -running out of dinosaur facts-

Him: Do you know what triceratops eats?

Me: Umm. No. Meat?

Him: It’s also an herbivore! -excited to display expert knowledge-

Me: Oh, I see.

Him: Do you know what stegosaurus eats?

Me: No.

Him: Plants!

Him: Do you know what spinosaurus eats?

Me: No…What does it eat?

Him: Kimchi.

Me: …

Me: What? Are you sure?

Him: Yeah. It eats kimchi.

Me: Who told you that? How do you know that?

Him: Oh wait…

Me: Are you just saying that because your spinosaurus figure is red?

Him: No, no, wait. It eats meat! I got it confused.

[I think I can see the kimchi]

As the grandfather clock in the living room struck twelve, his momentary confusion was dismissed by the late hour, and he visibly began to slouch into sleep. He described spinosaurus in further detail, informed me about how all triceratops were female (asexual reproduction?), and finally wrapped up the discussion.

Him: Hey, I love talking to you about dinosaurs. Let’s go to sleep now and talk about dinosaurs again tomorrow.

Me: Okay.

The declaration, its clarity, certainty, and hope rang in the dark, and in the space between us as he rolled a foot away from me, stretching his arms out to sleep. Lying there in the darkness, with this statement which would not come true, since I would be going back to Seoul the next day and the approval I finally received from him after a week of secretly trying to appeal to him as the best aunt ever, I felt… strange.

In an attempt to capture this feeling, my mind sifted through an archive of words, but only one stuck: Forever. Why the word “forever”? On the surface, it appeared to have no relation to the topic of dinosaurs or the promise of future bedtime stories. But that promise of tomorrow, which he suggested, perhaps out of habit, perhaps out of mimicry, for his parents must have used that tactic as they tried to convince him to stop eating dessert and have more tomorrow or to let go of a toy in a store for they would buy it for him tomorrow — lingered in the silence and stretched the moment out into forever. Because tomorrow was not going to come. And it would not be mourned after, because by tomorrow, he will have forgotten that we had this conversation at all. Perhaps he can remember vague pieces, but they will be inconsequential, and his stumbling, short-term memory will suck in, like a vacuum, even his expression of love of talking to me about dinosaurs.

Of course, it would be unfair to say this moment had zero consequences. On the contrary, our bedtime interaction had seeped deeply into him, forming the very tissues of his upcoming being. Instead of tethering his promise down to the person or the day, expecting him to be responsible for his words, expecting him to feel exactly the same about me tomorrow, or feeling like I have the right to feel betrayed if he doesn’t, all I could do was let go. He was not going to remember this sweet, sweet moment years from now. The purity that spoke with its high-pitched voice from underneath the taut, baby skin rang loud and clear, and it seemed to float away, into forever, not to stay in this world. In this world, I had to let go. In this world, enjoying the process of shaping him, being shaped by him, was all I could do. Suddenly continuity seemed like pain.

Childhood, which had seemed so long at the time, now appeared so short in retrospect. Around fifteen years of passive growth, and the rest of the time, a long stretch of every fiber and bone.