ADSactly Literature: Why is a raven like a writing desk?

ADSactly Literature: Why is a raven like a writing desk?

Mad Hatter: 'Why is a raven like a writing-desk?'

...

'Have you guessed the riddle yet?' the Hatter said, turning to Alice again.

'No, I give it up,' Alice replied: 'What’s the answer?'

'I haven’t the slightest idea,' said the Hatter'

I remember reading once in a book the answer to this famous riddle and being terribly excited, because no one had come up with a solution and yet, here it was, someone had finally got it. And then, I went online, to see what other people were making of it, and I realized I was wrong. People have come up with loads of solutions since Lewis Carroll wrote this incredibly puzzling riddle, and yet none is the right one. And they all are, at the same time.

Lewis Carroll (the pen name of mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) was a man who admittedly did not like endings. He couldn't bear saying goodbye or finding definite answers for something. A bit ironic, him being a mathematician and all, but I guess it only adds to the great enigma Carroll was. In fact, if you take a more careful look through his stories, you will find plenty of unanswered questions and endings open to interpretation, including the ending line of Through the Looking Glass:

Which do you think it was?

And of course, none is more strange than the Mad Hatter's riddle. Readers have been trying to find an answer to this question, deemed by many unanswerable, for over a hundred years. From fellow famous writers to people on the Internet, there have been many interpretations to the raven like a writing desk question and I would like to share some with you.

1. Poe wrote on both.

This answer is credited to one Sam Lloyd, puzzle enthusiast, in his Cyclopedia of Puzzles (1914). Famously, Edgar Allan Poe wrote, in his poem 'The Raven', of such a bird that haunted the author, at first creeping up on him, making him wonder who it was rapping on his door and then, slowly driving him mad at the memory of his beloved Lenore. It is, arguably, Poe's most famous poem.

And then, there's of course, the writing desk in which he wrote a lot of his work. It's a good answer, if you think about it.

2. Because there is a b in both, and because there is an n in neither.

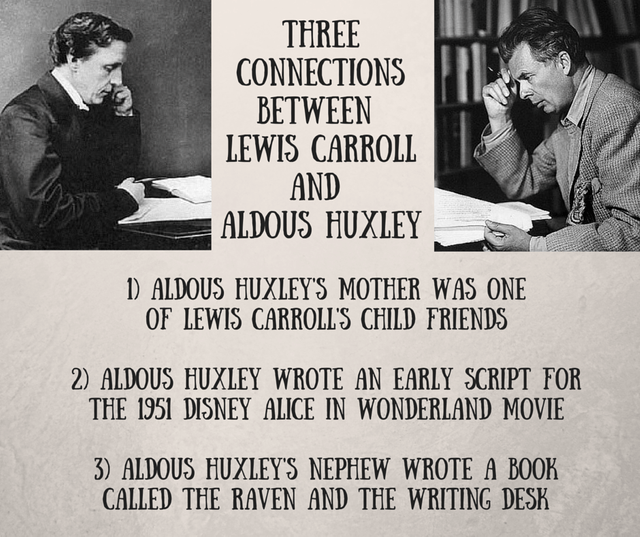

This marvellously absurd answer was found by Aldous Huxley (author of Brave New World) in a piece for Vanity Fair in 1928. Another technically correct answer, I think this one fits the best, simply because it's so strange. It doesn't seem like an answer at all, and yet it works, which makes me feel that the Mad Hatter would have approved.

3. Jumbled up letters

There have also been many answers that were really just plays on words, but also correct.

Because one has flapping fits and the other has fitting flaps.

Peter Veale

Because one is good for writing books and the other better for biting rooks.

George Simmers

Because a writing desk is a rest for pens and a raven is a pest for wrens.

Tony Weston

You can't say any of these aren't true, can you?

4. Answers before Carroll posed the question

Prehistoric depiction of a raven on cave wall source

Interestingly enough, although the question was made famous by Lewis Carroll in his book, it has been circulating from times immemorial and other famous people have written or spoken about it, long before Lewis Carroll was even born.

The 'Why is a raven like a writing desk?' question (or WIARLAWD, as it' frequently abbreviated) first appears written in the Bible, in the Book of Xerxes,

And ye shall travel the world with not a possession, not even an ass; yet ye shall but quothe the raven at its writing desk.

The Book of Xerxes (part of the Old Testament) has been dissected by Christian, Jewish and Muslim scholars alike, though none have been able to agree upon what it means. Some say that it is a reference to supernatural spirits and that it was supposed to have been dictated by Mohamed. Christian theorist (and also a famous children's writer) CS Lewis argued that it wasn't so much a riddle as an admonition. And some Jewish theorists argue that it is a reference to the Judaic proscription against pride. Though none seem to agree.

The famous Roman orator and statesman Cicero spoke on it as well, during the famous trial of Bluto, saying

"If not like a writing desk, what is a raven? But a winged creature that circles in heaven? Surely not. No, my fellow Romans, the raven is not just like the writing desk; the raven is the writing desk!

Worth mentioning that the Senate was swayed by Cicero and Bluto was acquitted.

Even Dante mentioned it in his famous Inferno,

And at the fifth circle of Hell, I found souls running in a circle, writing desks strapped to their heads, and ravens pecking out their eyes, while demons and evil spirits hurled racial epithets at them.

5. Lewis Carroll's take

And then, there is of course, the answer provided by Carroll himself. Though not nearly as famous as the question posed by his Mad Hatter, the solution Carroll seeks to provide does make some sort of sense. Carroll never wanted to actually answer this question. It was only intended as a joke, a funny absurd question, but his readers pestered him for an answer, forcing the writer to finally give in.

Enquiries have been so often addressed to me, as to whether any answer to the Hatter's Riddle can be imagined, that I may as well put on record here what seems to me to be a fairly appropriate answer, viz: 'Because it can produce a few notes, tho they are very flat; and it is never put with the wrong end in front!' This, however, is merely an afterthought; the Riddle, as originally invented, had no answer at all.

He included this bit in the preface of Alice in Wonderland in the 1896 (or 1897, unclear) edition. One thing that is interesting to note here is that Carroll originally wrote never as nevar (raven spelled backwards) in the answer above, but this little “typo” was removed by an editor. Get it? Put with the wrong end in front? Sure, it wasn't as epic as the riddle itself, but it was still an answer.

The question, of course, is open to interpretation. And that's, I believe, what makes it so incredible. That it can't really have any one answer, and so all of them work.

What is your take on it?

Sources: Uncyclopedia; StackExchange; Gizmodo.

Author: @honeydue

Every honest individual with good intentions is invited to join and offer skills, knowledge, energy, time or resources to various ongoing projects within The ADSactly Society. The channel is here: ADSactly and you are welcome.

Click on the coin to join our Discord Chat

To vote for @adsactly-witness first go to the witness voting page here:

https://whaleshares.io/~witnesses

Then find "adsactly-witness" and click on the upvote arrow next to the number and make it blue!

You can also choose @adsactly-witness as your proxy, then we will vote for witnesses on your behalf.

Seriously, I've never heard of this riddle before but I became engrossed into every bit of it and the research that goes into it.

I think the correlation that exist in raven and a writing desk lies in its prehistoric inspiration of writers. I've read some novels where staring at it inspires you to write. At some time in history too, the feather was been used as a pen. That's all I know.

You really have a deep thought provoking and amusing post here. Though funny to decipher yet serious to crack.

Posted using Partiko Android

I loved this article, not only because the topic is so thoroughly and well developed, but because it is about Carroll’s work. Can I play?

I’m a big fan of Carroll’s work, not only of his narrative but of his poetry—which is quite musical and pleasant to the ear even for those whose mother tongue is not English, like myself.

This riddle is a big teaser at the Mad Tea Party. In both novels Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, Carroll explores the notion of nonsense regarding language and its teaching (regarding children's formal education the Victorian England). Although it is in the latter where, undoubtedly, the narration discusses the irrationality of language more deeply, there are many teasers in the former, like this most famous riddle, which was never meant to have an actual answer.

Is meaning inherent to the word, or a word gets to mean by usage and thus convention? This old argument between Cratylus and Hermogenes brought to the table by Plato might have motivated this riddle—and a good part of the second book. Our good friend Carroll has had us rationalizing the answer. Different from reasoning, rationalizing means thinking inductively so as to reach a preconceived answer (a fallacy); see, for instance, the many answers essayed for this riddle (including one afterthought by the very Lewis Carroll); many will just fit, like you say.

I think, in the end, we are those children (including Alice) who came up with brilliant deductions about the meaning of words, creative puns and other joys of language. Fortunately, we don't have a sour governess or a bitter teacher to tell us its "nonsense."

Great work, @honeydue ☻♥

Very good and pertinent post if we consider that just yesterday 14 Lewis Carroll's death was commemorated. This is the riddle that the Mad Hatter poses to Alice in Chapter VII of Alice in Wonderland, while drinking tea. Alicia says she knows the answer, but a sudden turn in the conversation prevents her from saying it. Lewis Carroll himself acknowledged in a prologue to the book written in 1896 that when he raised it he had not thought about what the solution might be, but the enigma became so famous that he was forced to offer an explanation, which is the one we all know and which is also an enigma because it is a play on words. I prefer to stay and say what Alice said in the play:

Excellent publication, @honeydue. Thanks to you for sharing and to @adsactly for publishing.

This post is very important for you.............good.........good........good.........

Good job

Post that give readers insight. Peeling literary works with a puzzle topic that can be answered with many answers, and answers that are not to blame. Every answer is reasonable and acceptable with common sense.

and what I like more is the answer given using the logical language and the beauty of diction which makes rhyme good as a poem.

The love of @honeydue

Thank you @adsactly

Thank you Steemit

Warm greetings from Indonesia

Hi, @adsactly!

You just got a 0.61% upvote from SteemPlus!

To get higher upvotes, earn more SteemPlus Points (SPP). On your Steemit wallet, check your SPP balance and click on "How to earn SPP?" to find out all the ways to earn.

If you're not using SteemPlus yet, please check our last posts in here to see the many ways in which SteemPlus can improve your Steem experience on Steemit and Busy.

I always thought the riddle the 'riddle of life' and truly it has no ONE answer, but many and each and every one of those never quite add up, much like the lives of all the world's people.

I love lewis carrol and Aldox huxley oh and Poe. Probably not needed saying, but had to say none the less :)

A very interesting and pleasant post, @honeydue. What you present to us puts us before the evidence that Carroll's work, undoubtedly, is directed by two major aspects: illogicity and linguistic play, both converging in the unstable character of meaning. Similar situations can be found both in Alicia in Wonderland and in Alicia through the mirror. Your inquiry, also very playful, by the way, reflects it quite well for the famous question of the Hatter; but we will find the same in the encounters with the Queen, with the Cheshire cat, or with Humpty-Dumpty. These aspects, beyond the anecdotal nature of their narrations, make this work a major contribution to literature and even the philosophy of language. Thank you for your article, and @adsactly for its publication.