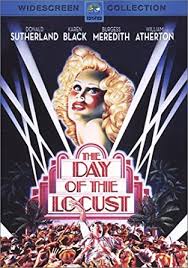

DAY OF THE LOCUST- NATHANIEL WEST: CLOSE READING

--CLOSE READING: SATIRIZATION OF MAYBELLE LOOMIS IN NATHANIEL WEST'S "DAY OF THE LOCUST": SOCIAL COMMENTARY ABOUT HOLLYWOOD--

Right from the beginning of Nathaniel West’s novel, The Day of the Locust, main character Tod Hackett establishes arguably the most prominent idea of the entire story, which is that there are two types of people who exist in Hollywood, California. The first category of people are those who dress and act the part of an occupation they do not take part in. The second category of people are those who are going nowhere in life. They possess a particular sort of internal hatred, and Tod specifically identifies them as the people who “come to California to die” (West, 60). However, as the narrative progresses, the reader encounters a peculiar character named Maybelle Loomis, who interestingly falls into both of these categories of the Hollywood population.

Maybelle Loomis first comes into the picture when Tod and Homer are outside, and they spot her loudly searching for her lost son, Adore. The whole scene in itself is merely a dramaticized act, because Maybelle is aware that her son is merely teasing her; yet, in her dialogue with Tod and Homer, she continues to play the role of a preposterous Californian mother. Through this encounter with Maybelle Loomis, West intends to shed light upon the absurdity of her type that exist in Hollywood. Namely, those who routinely exhibit shortsightedness, arrogance, and a fruitless ambition for fame. West satirizes this group of people through the character of Maybelle Loomis as he utilizes exaggerated diction and irony, thereby suggesting the tone and attitude one should take towards similar individuals.

One way that West satirizes this particular group of Californians is through the exaggerated diction describing Maybelle Loomis during her conversation with Tod and Homer. In this manner, Maybelle will serve as a representation for this group. Just before Maybelle meets the men, as she is looking for Adore, the narrator states that she is yelling for him in a “high soprano voice” (137). So right from the start of this encounter, the reader gets the idea that this woman is, in some sense, going to be highly theatrical and exhibit some piercing characteristics. When she finally meets Tod and Homer, she displays a series of reactions and gestures that further prove her amplified, yet inconsistent nature. For instance, Maybelle goes from giving a “gesture of helplessness,” to laughing, to angrily snapping, to speaking calmly all within the brief duration of this conversation (138).

It is quite apparent to the reader that this is not how the average human being interacts with other people. To some extent, Maybelle is either insane, perpetually acting, or perhaps both. Through the atypicality of her behavior, West could be suggesting that Hollywood has conditioned people to a point where they always feel the need to be putting on a performance, and oftentimes, for self-interested motives. At this point, the reader is aware of Maybelle’s passion for acting, which next calls into question her motives for putting her 8-year-old son into the Hollywood industries at such a young age.

Next, West satirizes this particular group of Californians through the irony and absurdity of Maybelle’s reasoning and actions. The first red flag that comes to the attention of the reader is when Maybelle calls California “a paradise on earth” (138). By this point in the novel, the reader is fully aware of how negatively California is portrayed by West. He or she has seen how rudeness, corruption, and blatant amorality plagues the people and industries in Hollywood. Therefore, as Maybelle ironically speaks so highly of California, one cannot help but cross-examine both her credibility and moral code.

The next absurd statement that Maybelle makes is when she tells Tod and Homer that she has to live in California “on account of [Adore’s] career” (138). Maybelle Loomis does not seem to have her own career of any sort; rather, she utilizes her 8-year old son as a source of income for their family. This is absurd because in normal society, a parent labors for their family’s income, not the child. As demonstrated through Maybelle’s life decisions, West suggests that California possesses a rationale so distorted that parents are willing to put their young children into the corrupt industry of Hollywood for their own personal gain. This is apparently a popular norm amongst other people too, as Maybelle explains to Tod and Homer how difficult it has been for Adore to get his big break. She claims that Adore would be a big star “if it weren’t for favoritism,” and goes on to say “it ain’t talent. It’s pull. What’s Shirley Temple got that he ain’t got?” (138).

The first implication of this remark is the existence of the thousands of children Adore must compete against to become prominent in entertainment. This means that all of these children are being forced into the corrupt business of Hollywood as well. West, in addition to many others, question the appropriateness of these parental decisions. Throughout the course of the novel thus far, the reader has seen how inconsiderate, aggressive, and unprincipled people involved with Hollywood industries are. Therefore, one can practically draw a conclusion that children who are exposed to this business at a young age will begin developing these characteristics early, which will only enhance their dishonorable qualities as adults.

The second implication of this remark is the fruitless efforts of Maybelle passionately pushing Adore into the entertainment industry. This could be fruitless in various ways. For instance, Adore could potentially lack talent, and Maybelle enviously denies his inability to be successful in this area. Or perhaps she is correct about success being unrelated to talent, but rather to influence and politics in Hollywood. Regardless of where the reasoning lies, West clearly suggests that involving a young child in show business is wrong on multiple levels due to the overall unethicality of the industry.

Through the character of Maybelle Loomis, Nathaniel West makes critical social commentary on a particular group of individuals in Hollywood; that is, those who foolishly force their children into the Hollywood industry for self-interested motives. For Maybelle, her rationale could be explained due to the fact that she falls into both of the categories of Californians that Tod creates: those who put on facades and those who “come to California to die” (60). Maybelle falls into the first category of individuals because she constantly acting like an actress, even though she is far from ever becoming one in the industry. It is likely that she had aspired to become one in the past, but because of her “plump” figure, she never made it (137). Thus, she feels the need to compensate by pushing her son, Adore, into show business. Maybelle also falls into the second category of individuals, because she is chasing her dead dreams through her son. Her internal resentment for never becoming successful herself could have fueled her vehement behavior, endeavors for her child, and general adoration of Hollywood.

Sadly, Maybelle Loomis will probably make it nowhere in life, and all of her efforts will be fruitless. But ultimately, this is the point that West is trying to make about this overly ambitious group of people in California: that being, those who come to Hollywood in search of fame are not only set up to fail miserably, but will also become direct subjects to the corrupt system. In time, these individuals will regretfully find the Hollywood experience to be vapid, vain, and frustrating.

Works Cited:

West, Nathanael. Miss Lonelyhearts ; &, The Day of the Locust. New Directions, 2009.

@resteemator is a new bot casting votes for its followers. Follow @resteemator and vote this comment to increase your chance to be voted in the future!