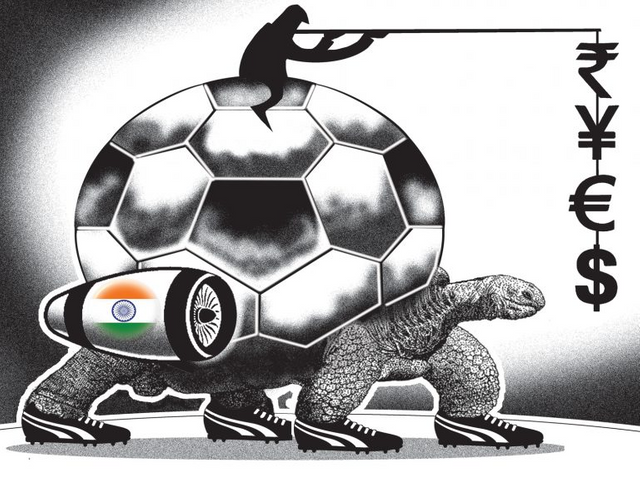

India At The World Cup? Indian football has fallen off a cliff, here’s what it will take to revive it

Every four years when the entire globe is caught up in World Cup fever, one question nags Indian sports fans: why has India never ever been part of the world’s premier football tournament? I had a long conversation last week with a Swiss journalist, who wanted to know the reasons behind India’s poor performance in sport in general and football in particular.

The journalist had a right to be bemused by India’s sporting record. Switzerland, a nation of 8.5 million people, was not only playing their tenth World Cup but had also qualified for this year’s knockouts. In contrast, the closest India has come to playing the World Cup was in 1950 when India was invited, but could not afford the passage to Brazil.

What the journalist was unaware of was that India, currently placed at 97 in the Fifa rankings, wasn’t always so poor in football. In the 1948 London Olympics, the barefoot Indian footballers had so impressed King George VI that he apparently asked one of them, Sailen Manna, to roll up his trousers to check if his legs were made of steel.

But more than the novelty of India’s barefoot footballers, the Indian team of the late 1950s and early 1960s, under coach Syed Abdul Rahim, was an Asian powerhouse. The team, comprising players like PK Banerjee, Chuni Goswami and Jarnail Singh, beat future Asian football powers, Japan and South Korea, to win the 1962 Asian Games gold. Even in the 1970 Asiad India won a bronze, possibly its last major international title. Since then it has been a downward slide.

While a clutch of reasons can be offered for India’s decline – poor infrastructure and coaching, absence of a proper professional structure, confinement of the game to certain pockets of India and the popularity of cricket – it still remains a mystery why the slide was so calamitous. Indeed Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski, the authors of ‘Soccernomics’, famously labelled India as the worst footballing nation given its population, GDP and sporting experience.

So, is there a way out? Several studies have shown that not just for football, but for sports in general the wealthier countries tend to do better. But there are many exceptions to the rule. One route is to invest in football infrastructure. This is the path being followed by China to achieve its professed goal of having a team capable of winning the World Cup by 2050. Chinese President Xi Jinping has put his weight behind this initiative and expressed the desire of having 20,000 football centres and 70,000 pitches in place by 2020.

Chinese football clubs have also paid astronomical sums to attract foreign stars to play in China and improve the country’s standard of football. However, the efforts are yet to pay off. China is currently placed at 75 in the Fifa rankings and has qualified for the World Cup only once. This might have something to do with team sports not being as amenable to the kind of state intervention that China has put in place to harvest Olympic medals. In fact, China has notably been less successful in team sports compared to individual events.

However, investment in football infrastructure has paid dividends in other, smaller countries. A statistical model created by Economist magazine – based not only on GDP and population, but also football’s popularity and Olympic medals won – found that countries like Uruguay are performing much better than expected. This is partly due to a national scheme called Baby Football involving thousands of children from ages four to 13. Similarly tiny Iceland, which has a population of under 3,50,000 and has of late been punching well above its weight, has over 600 coaches working with clubs at the grassroots level. Such schemes are what India should aim at, though they are also more difficult to replicate in larger countries.

Yet another route to success is to export players to competitive leagues as well as tap into the diaspora. This is what many of the African as well as Balkan countries have done to great effect. Countries like Senegal not only export players to top leagues in Europe, but also attract diaspora talent when putting together its national team.

Croatia has a team that is entirely composed of players turning out in foreign leagues. To a lesser extent, some Asian countries like Japan and South Korea are following this route. Again this is a model that India has been unable to replicate mainly due to its marginal presence on the international stage. Indeed, no Indian player has ever played at the highest level in a foreign league.

For India, neither a Chinese-style investment nor players in foreign leagues is feasible. To even qualify for the World Cup, India has to go through the hard grind of investing in grassroots programmes and infrastructure, preferably in locations such as the northeast, Kerala, Goa and Bengal, where interest in football is high.

Some of the ingredients for footballing success are already present: economic growth, a professional league with decent salaries and new centres of football. Some of this has contributed to India’s recent rise in the rankings. However, to reach the next level, the passion for football, which exists despite cricket’s omnipresence, must be harnessed.

For a start, the kids who are following the World Cup avidly need to leave the couch and start kicking the ball. There is no substitute to the timeworn policy of catching talent young and nurturing it.