What is Money?

In order to make sense of the economy, an understanding of the lubricant that keeps the economic machine running is needed. That lubricant, is money. Many things have been used as money at different times in the past: shells, beads, grains, gold and even livestock to name a few.

Today, money is largely government issued coins and paper notes, or an electronic bank balance that represents a certain value of coins and paper notes. Increasingly, it is the latter (electronic) version that dominates the money supply. Investopedia defines money as “an officially-issued legal tender generally consisting of notes and coin, and is the circulating medium of exchange as defined by a government”.

In historical terms, this form of money is relatively new. Forty-six years old as of August 16, 1971 to be exact. Before then, gold and silver had been used as money (either directly, or through government issued paper notes that could be redeemed for physical gold or silver at a fixed rate) for over 2,500 years dating back to 560 B.C. or even earlier depending on which historical record you subscribe to. The point here is that gold and silver had been the preferred form of money for the vast majority of recorded human history.

Why gold and silver? Gold and silver are two of only ninety-four elements known to man that can be found in their natural state on earth. Elements cannot be broken down into simpler components so gold and silver can neither be created nor destroyed, making it impossible to counterfeit. Unlike many of the other elements, they exist in solid form at room temperature, do not corrode, and are malleable which enables them to be easily minted into standard units such as coins or ingots.

Gold and silver satisfy all the properties needed for an item to function as money: they can be used as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and in terms of physical properties, they are portable, durable, divisible and fungible.

It’s also worth noting that gold is rarer than silver by a ratio of approximately 15:1. In other words, there are 15 ounces of silver in the world for every ounce of gold. Hence gold has always been considered more valuable than silver. Furthermore, there are now many modern industrial uses for silver such as nuclear reactors, solar energy, RFID chips, touchscreens, semiconductors and others, leaving gold in a category of its own as the standout contender for money since its industrial applications are far more limited.

So, what prompted the world to abandon gold in favour of non-gold coins, paper and electronic money after more than 25 centuries? Conventional wisdom says that the modern economy simply evolved beyond the practical need for gold. We now have the internet, and computers with ever-increasing processing power that can accurately and securely transfer electronic money between cities, countries and continents. Gold no longer meets the portability requirement of money in the context of today’s increasingly global economy.

On the face of it, this reasoning makes complete sense. Imagine buying a car from Japan and having to ship a lump of gold across multiple continents to pay for it. It’s simply not practical. And for that reason, the vast majority of people blindly accept that gold is now just a commodity used to make fancy watches and jewellery, with no other meaningful purpose. It’s too cumbersome to be used as money in the modern economy.

Unfortunately, it’s not quite as simple as that. Government’s issued notes long before computers and the internet, but for over a century they were directly tied to gold e.g. you could take a US$20 bill to the bank and redeem the equivalent in gold at a fixed conversion rate. In the same way, electronic money that came along many years after the gold standard was abolished could have been tied to gold enabling all the efficiencies of modern technology to facilitate commerce, without abandoning the role of gold as the ultimate form of money.

That brings us back to the same question: what prompted the world to abandon gold in favour of non-gold coins, paper and electronic money after more than 25 centuries?

The answer lies in history, so let’s go back a few centuries and observe how gold performed as money in the past. Since it was the US Dollar that replaced gold as money in 1971, and remains the world’s reserve currency today, we’ll focus on US monetary history.

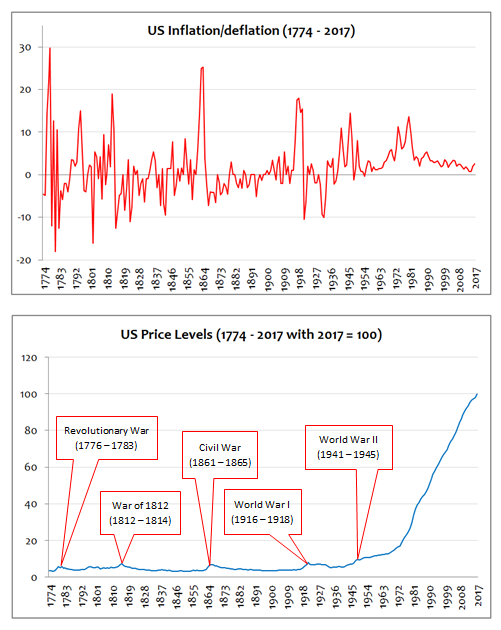

The two graphs that follow show US inflation and price history over a period of almost 250 years. Inflation indicates the extent to which prices are rising, or in the case of negative inflation or deflation, how much they are falling. Generally speaking, high levels of inflation or deflation are undesirable as they are linked to periods of economic stress. Price levels indicate the net impact of inflation or deflation on the value of money.

Looking at US inflation history, we notice considerable volatility in the 1700’s, 1800’s and the first half of the 1900’s. Inflation spiked to almost 30% in the 1770’s! However, following every period of inflation was an offsetting period of negative inflation, or deflation. That is until shortly after World War II, where we’ve since observed seven decades and counting of inflation, with zero offsetting deflation.

If we look at the same data expressed in terms of price levels, we observe a different story: price stability for over 150 years before an almost exponential increase in prices from around 1944 to the present day. Now look at the labels corresponding to significant historical events, or more specifically, wars.

It’s no coincidence that The Revolutionary War, The War of 1812, The Civil War, World War I and World War II all occurred during periods of high inflation, or rather that the wars themselves caused periods of high inflation.

How do wars cause inflation? Well, quite simply because wars are often too expensive for governments to pay for using their gold reserves. To engage in war, governments need to increase the money supply. It can do this in two ways: 1) borrow money 2) create money. In the latter case, the government can’t create gold so it created money by printing legal tender in the form of paper notes. Either way, the spending increase during war puts upward pressure on prices which leads to inflation. As the loans are repaid or as excess legal tender is removed from circulation after the war, prices deflate and revert back to their original levels.

The latter is precisely what happened during the Revolutionary War when the government issued ‘Continentals’ shortly after the war began. Continentals were bits of paper issued by the government that carried an entitlement to a certain value of gold or silver. The notes literally stated: “This Bill entitles the Bearer to receive FIVE SPANISH MILLED DOLLARS, or the Value thereof in GOLD or SILVER, according to the resolutions of the CONGRESS.” There were different notes for different denominations (one dollar, two dollars, twenty dollars etc.) but other than that the wording was the same.

At the time, the US didn’t have its own mint or coinage hence Spanish coins were widely used due to advanced milling processes that gave them unparalleled size and weight consistency and made them widely accepted in many countries. However it wasn’t the coin itself but rather the gold it was made from that was valuable, hence Continentals could be exchanged for Spanish Dollars or the equivalent in Gold or Silver.

As Continentals became widely accepted, more and more were printed to fund the war effort, even though the government didn’t actually have the gold to back them up. When people began to realise this, they started to trade Two Continental Dollars for a single Dollar coin, then three, then four… the problem was exacerbated by the British government flooding the market with counterfeit Continentals in an act of economic warfare.

As more Continentals were issued, their value dropped, and by the end of the war they were worth a fraction of their face value to the extent they were deemed worthless. The subsequent reversion to gold caused prices to fall back (deflation) to their original levels.

In the War of 1812, the government borrowed money to fund the war effort instead of printing paper money. Accelerated spending during the war had the same effect of increased inflation but the debt burden crippled government finances leading to a default on Treasury notes in 1814. Taxes were subsequently raised and it took another twenty-three deflationary years for the government to repay the debt it accrued during the war.

During the Civil War, the government reverted back to paper currency tactics, this time issuing Demand Notes that became known as ‘Greenbacks’, as they were printed using green ink on one side. When the first batch of Demand Notes proved to be insufficient, ‘United States Notes’ were printed with the same green ink on one side. Neither was backed by gold, silver or any other asset.

As before, inflation spiked during the war, but as the supply of Greenbacks was gradually reduced after the war, the resulting deflation took price levels back to the pre-war rate of $20.67 per ounce of gold. Unlike Continentals that were rendered useless after the Revolutionary War, the Greenback survived the Civil War, albeit at a lower exchange rate to gold. This was certainly a better outcome than the devastating effects of debt financing employed during the War of 1812.

So, at this point, we’ve observed 3 wars over a 150-year period with Gold as the ultimate form of money, and aside from some temporary spikes during times of war, there was practically no change in price levels. An ounce of gold in the late 1700’s would buy the same goods and services as an ounce of gold in the 1910’s. We also observed the emergence of a ‘fiat’ currency that operated as a second form of money alongside gold. The fiat currency gave the government an attractive tool to spend beyond its means as needed, without the burden of debt.

The excess spending would be reflected in the devalued fiat relative to gold since the more money that is printed, the less value each existing unit is worth. Consider a government that issues 1 million dollars of fiat currency and let’s say the price of gold is $1 per ounce. If the government prints another million dollars of paper notes, but the amount of gold hasn’t changed, it would now take $2 to buy an ounce of gold. In other words, the price of gold has doubled or in terms of gold, the value of paper currency has halved.

This brings us to an important distinction, and that is between gold money and fiat currency. To this point, we’ve used the terms ‘money’ and ‘currency’ quite loosely, sometimes interchanging between the two. This is quite possibly the biggest conceptual error in economics and finance. In addition to the properties of being a medium of exchange, a unit of account, portable, durable, divisible and fungible, money is also a store of value as its supply is limited. Currency on the other hand, serves all the aforementioned functions of money, but it does not maintain its value.

Gold is money. Government issued legal tender is currency. The reason that the former is a store of value while the latter is not, is due to scarcity. Recall that gold is an element; it cannot be created or destroyed. There is only an estimated 175,000 tonnes of gold discovered on earth which is enough to fill 2-3 Olympic sized swimming pools. Currency on the other hand, can be printed at the government’s will. In fact, these days it doesn’t even need to be printed, legal tender can be created with a few keyboard strokes on a Central Bank computer.

Remember, a critical feature of money is that it acts as a store of value. Gold clearly meets this criterion whilst currency does not. Gold is therefore money and government issued legal tender is currency.

Misunderstanding of the distinction between money and currency is so widespread, it pervades just about every textbook on economics and finance, the media, and the even the banking and finance industry itself. Even Investopedia’s definition of ‘money’ is actually the definition of currency. Currency has become so synonymous with Money that the majority of bankers, accountants and other finance professionals do not differentiate between the two, or at best they simply ignore the difference.

At the end of the day, money and currency are simply a medium of exchange. The only difference is that one can be manipulated while the other cannot. Just as we price goods and services in the currency of US Dollars, we can also price goods and services in the money of gold.

I can’t emphasize enough how important it is to make the distinction between money and currency if you really want to understand how the economy works. Drawing a line between money and currency will completely liberate the way you think about economics and finance. Currency and Money are both mediums of exchange, but only Money is a store of value.

Disclaimer: I'm not a "gold bug". I do not trade gold, nor do I recommend buying or selling gold for speculative purposes. The distinction between money and currency as defined above is designed to help you better understand the economy and how it really works. The government could issue paper money just as it issues paper currency, the only difference would be that the quantity of money is fixed while the quantity of paper currency can be increased in perpetuity. It’s the lack of trust in the government to keep its promise not to debase the money supply that makes gold a more reliable monetary instrument. By this definition, digital currencies are actually more akin to digital money since their quantity is limited.

detailed

too much detail?

it is a complex subject and most people do not have time to read one long post due to daily hustle and bustle.

i think u could have broken it down to several smaller posts as it would have been easier to digest.

it is a very important topic and we have let the bankers dictate our world because we have been ignorant.

thanks for posting though in any method that u choose. i appreciate it.

Fair enough.... it's actually the first chapter of a book I've written that you can find on www.edwineconomics.com I'm new to steemit so just cut and pasted the first chapter to see how much interest there is on this topic. Thanks for the feedback. I'll post some of my shorter blogs here and see how they are received. Cheers.