Thoughts on the Decentralisation of Money 2: Commodity Currencies

In my previous post on decentralisation of money, I briefly examined the role of the state in domestic and international monetary arrangements through history. In a series of my next posts, I will delve into a bit more detailed history of the modern international monetary system, ranging from the gold standard regime to the contemporary system of state fiat currencies. The objective of this exercise in economic history will be to position the recent rise of cryptocurrencies into a broader historical context.

Long before the rise of industrial capitalism in 19th century, precious metals such as gold and silver were favourable means for financing trade and settlement of debts amongst merchants and public authorities. The upsurge of industrial capitalism, which accelerated the expansion of foreign trade, roughly coincided with the formation of modern nation states. This, in turn, fostered the creation of several nonconvertible national currencies that weren’t backed by any precious metal. Nonetheless, precious metals remained an anchor of international monetary transactions. In the first half of 19th century, most states used gold to settle international transactions, others used silver, and some states used both. Bimetallic system could function properly as long as the exchange ratio between gold and silver remained stable. In 1870, however, the price of silver dramatically collapsed, which paved way to an undisputed role of gold as an exclusive world commodity-money. This, of course, did not mean that international transactions were settled with gold as such. More often, merchants used banknotes, initially issued by commercial banks that promised to honour the notes in gold. Later on, the issuing of banknotes became an exclusive right of state central banks, that, at first, also backed the notes with gold reserves.

The 19th century gold standard system, based on a single global currency and fixed exchange rates, definitely contributed to the stability of the international monetary system, which was also reflected in the absence of serious military conflicts between leading world nation sates. The stability of the system did not result from active state intervention and regulation, but rather from an automatic mechanism of adjustment of trade imbalances – note that, at that time, central banks did not yet exist. The role of the states was limited to providing the national economy with a sufficient amount of money in accordance with the available amount of gold, and to react to the adjustment mechanism by either buying or selling gold reserves. The adjustment mechanism was founded upon the influx of gold reserves from countries with current account deficits to the countries with current account surpluses. In theory, the logic of the mechanism is the following one: a country with negative net sales abroad decreases its gold reserves (reserves flee to a country with a positive trade balance) and thereby limits the domestic money supply. As a consequence, domestic demand for import commodities drops, which causes a fall in the level of prices (deflation), and, in turn, increases exports. The renewed rise in exports thus terminates the current account deficit.

On the one hand, the gold standard regime, based on an unrestricted international mobility of capital, brought about an unprecedented growth of international trade and accelerated industrial development all over the world. On the other hand, the socio-economic costs for the smooth functioning of the aforementioned adjustment mechanism, were often severe. Deflationary policies of restricting domestic demand, by means of which the countries with trade deficits adjusted to current account imbalances, frequently caused recessions, sharp declines in wages and massive unemployment.

The gold standard regime could only function as long as national labour markets were flexible. Since the exchange rates between different currencies were fixed, countries could not resort to currency devaluation to tackle increased pressures of international competition. They primarily relied on labour markets that had to be flexible enough to allow for swift adjustments in the level of wages. However, after World War I, the labour markets in leading Western economies were becoming ever more rigid: their flexibility was gradually eroded by tighter state labour regulations, growing welfare policies, increased bargaining power of trade unions, etc. Another precondition for the unimpeded functioning of the gold standard regime was international mobility of capital. Yet, after the World War I, the leading economies were increasingly adopting protectionist policies that restricted international trade and capital flows. This coincided with the process, whereby the national central banks that started to emerge in the early 20th century – the Federal Reserve, for instance, was created in 1913 –, were gradually starting to dictate the terms of domestic monetary policies.

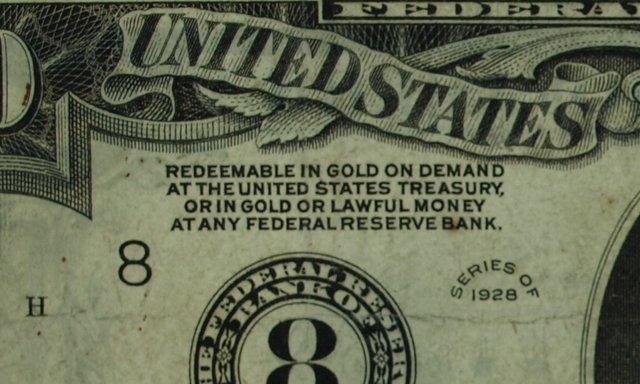

Even though, after World War I, central banks were still holding gold reserves, large amounts of gold were withdrawn from circulation. At first, the issuing of notes by the central banks had to be at least partially covered with the gold reserves: for example, the Federal Reserve Act, required that the FED had 40% of its demand notes covered with gold. This meant that central banks could not simply issue as much notes as they willed: if there was a demand to convert notes to gold, the gold reserves decreased, and the central bank could, in turn, only issue a smaller number of notes. The limits on the issuing of notes turned out to be a problem in times of crises, most notably in the Great Depression of 1929. When crises struck, there was a run on gold, but at the same time, the need for credit grew and the banks required more banknotes. The fractional gold-reserve banking system thus sharply limited the supply of banknotes precisely in times when demand for banknotes was at its peak. As a consequence, many states sooner or later started to loosen regulations that required convertibility of banknotes into gold.

The erosion of flexible labour markets, adoption of protectionist policies and the rise of national monetary policies directed by state backed central banks, eventually became incompatible with the foundations of the gold standard regime. The control of domestic money supply thus shifted from the world-wide market automatism, to domestic policies of national central banks. The states, with the help of newly formed central banks, began to safeguard their national economies from ever more frequent volatilities of the international financial system by adopting capital controls, especially by curtailing international credit and investment flows. The gold standard regime grinded to a halt, and a turbulent era that ended with World War II, followed. One had to wait until 1944 for a new orderly international monetary regime to be established. This was the year when the Bretton-Woods agreement, that established new rules for financial and commercial relations between leading world economies, was signed. In the next post, my historical analysis is to be continued with the examination of the Bretton-Woods system.

References

- Barry Eichengreen (2008), Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System, Princeton University Press: Princeton and Oxford.

- Karl Polany (2001), The Great Transformation: Origins of our Time, Beacon Press: Boston Massachusetts.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://stefanfurlan.com/2017/12/16/thoughts-on-the-decentralisation-of-money-2-commodity-currencies/

Congratulations @stefanfurlan! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP