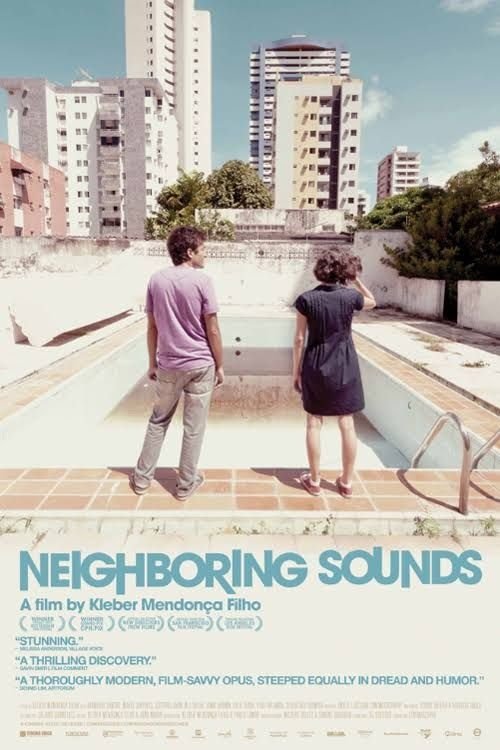

Screening 4: Neighbouring Sounds

The website D Movies - formerly Dirty Movies but I think people got the wrong idea - has collaborated with the cultural section of the Brazilian Embassy in London to screen a series of recent Brazilian films. The selling point is that the films that aren’t well-known to the British public but show a side to the country that is far removed (maybe not that far) of the portmanteau film ‘Rio, I Love You’ in which Sugar Loaf Mountain, football and the statue of Christ the Redeemer feature prominently.

A number of Brazilian directors have dabbled in Western cinema, most notably Fernando Mereilles with the British thriller ‘The Constant Gardener’ and Jose Padilha with the big budget remake of ‘Robocop’ (zzz). Those who stay behind cement Brazil’s reputation as a powerful filmmaking nation, capable of truth and innovation in its storytelling, though Argentina, its Andean cousin, is not far behind - evidenced by Pablo Trapero’s ‘The Clan’.

The five films that D Movies is showcasing are ‘Batguano’ (2014, dir: Tavinho Teixeira); ‘Dead Girl’s Feast' (2011, dir: Matheus Nachtergaele); ‘Rat Fever’ (2011, dir: Cláudio Assis); ‘Neighbouring Sounds’ (2012, dir: Kleber Mendonça Filho) and ‘Neon Bull’ (2015, dir: Gabriel Mascaro). The films are at the very least provocative and at their best revelatory. ‘Neighbouring Sounds’, the only film of the five to get a UK release, left me gob-smacked.

‘Neighbouring Sounds’ (O soma o redor) is audacious in its construction and execution. A better English title might be ‘Sounds of the Neighbourhood’ but the other title suggests proximity. Set in Recife, it is about a street in which almost every property is owned by a wealthy man, Francisco who made his fortune in a sugar mill. His two grandsons, one who works for Francisco, the other is a petty thief, live close by. After the theft of a car stereo, the neighbourhood is canvassed by a trio of men offering security services. They set up on the street and patrol from seven pm to seven am.

We spend time between houses. A single mother, Beatrice (Maeve Jinkings) with two school-age children decides to give the barking dog next door sleeping pills caked in raw meat and then spends the next day spying on the dog with binoculars praying that she hasn’t killed it. (‘It’s all right,’ her daughter tells her, ‘the dog’s still breathing’.) The young grandson, Joao (Gustavo Jahn) has a vigorous relationship with a girl he met at a party and is teased about marriage. She grew up nearby and wants to see her old house. The maid brings her children with her to work, including her eldest who has just started working nights. The single mother smokes marijuana away from her children, using her vacuum cleaner to extract the fumes in a scene that has to be seen to be believed. As for what she does with the washing machine on spin cycle – her children couldn’t even guess.

In as far as the film having a plot it is about Joao retrieving his girlfriend’s car stereo, the neighbours debating the security detail and the property owner receiving unexpected news at his grand niece’s birthday party. The film is about incident more than plot, but builds rather like ‘Do the Right Thing’ to a confrontation.

In one scene, as a woman is shown a property, a ball is kicked over the wall. A young boy waits expectantly for its return – waits and waits. Meanwhile, the potential tenant notes that a woman recently committed suicide in the property – couldn’t she have a discount? When she sees the floral tribute on a landing, she is out of there. Finally, after the young boy leaves, the ball is kicked back into the street.

Some of the incidents are drily humorous. A young Argentine man wanders down the street unable to get his bearings and approaches the security detail. ‘I was at a party. I left my car there. I don’t recognise where I am.’ One man calls his colleague at the other end of the street. ‘You know of a party last night?’ ‘Sure. At Camille Claudel house. Send him down here.’ The Argentine is waved forward. We don’t find out if the man gets his car back.

Other scenes are more surreal and symbolic, notably when the young man and his girlfriend visit an abandoned cinema. The man plays at being cashier. The girl ‘buys’ a ticket. There is no inside, just overgrown grass in which the couple gambol. The playfulness of the scene and symbolic import – cinema overgrown with weeds – suggests early Jean-Luc Godard, a comment on the old guard.

Sound is as you might expect used prominently – dog barking, lights humming, motor engines roaring. But there are also dream sequences of figures in shadows running through the neighbourhood. The single mother sees three men on the roof of a neighbour’s house. The lead security man takes a maid to a house he is supposed to be protecting. He leads her to the master bedroom, begins to undress her. Then a figure darts past the open doorway.

The film describes the palpable tension between past and present, rich and poor. It hangs in the air like cigarette smoke. We don’t yet know if it will kill us.