Most Significant Figures in History #2: Napoleon Bonaparte

Main Facts

Napoleon Bonaparte (15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821) was a French military and political leader who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led several successful campaigns during the French Revolutionary Wars. As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 until 1814, and again briefly in 1815. Napoleon dominated European and global affairs for more than a decade while leading France against a series of coalitions in the Napoleonic Wars. He won most of these wars and the vast majority of his battles, building a large empire that ruled over continental Europe before its final collapse in 1815. Napoleon's political and cultural legacy has endured as one of the most celebrated and controversial leaders in human history.

Early Life

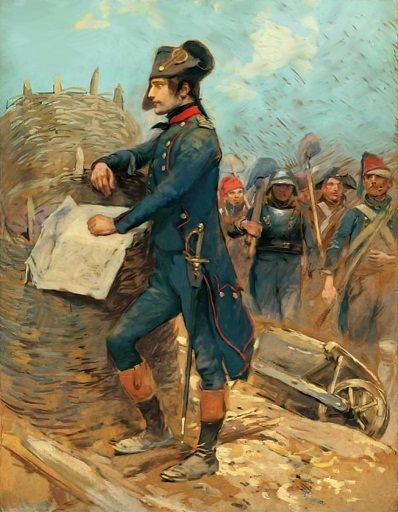

He was born to a relatively modest family from the minor nobility. When the Revolution broke out in 1789, Napoleon was serving as an artillery officer in the French army. Seizing the new opportunities presented by the Revolution, he rapidly rose through the ranks of the military, becoming a general at age 24.

Early Career

Upon graduating in September 1785, Bonaparte was commissioned a second lieutenant. He served in Valence and Auxonne until after the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789, and took nearly two years' leave in Corsica and Paris during this period.

He spent the early years of the Revolution in Corsica, fighting in a complex three-way struggle among royalists, revolutionaries, and Corsican nationalists. He was a supporter of the republican Jacobin movement, organising clubs in Corsica, and was given command over a battalion of volunteers. He was promoted to captain in the regular army in July 1792, despite exceeding his leave of absence and leading a riot against French troops.

By 1795, Bonaparte had become engaged to Désirée Clary. Désirée's sister Julie Clary had married Bonaparte's elder brother Joseph.

In May 1798, Bonaparte was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences. His Egyptian expedition included a group of 167 scientists, with mathematicians, naturalists, chemists, and geodesists among them. Their discoveries included the Rosetta Stone, and their work was published in the Description de l'Égypte in 1809.

Ruler of France

While in Egypt, Bonaparte stayed informed of European affairs. He learned that France had suffered a series of defeats in the War of the Second Coalition. On 24 August 1799, he took advantage of the temporary departure of British ships from French coastal ports and set sail for France, despite the fact that he had received no explicit orders from Paris.

Unknown to Bonaparte, the Directory had sent him orders to return to ward off possible invasions of French soil, but poor lines of communication prevented the delivery of these messages. By the time that he reached Paris in October, France's situation had been improved by a series of victories. The Republic, however, was bankrupt and the ineffective Directory was unpopular with the French population. The Directory discussed Bonaparte's "desertion" but was too weak to punish him.

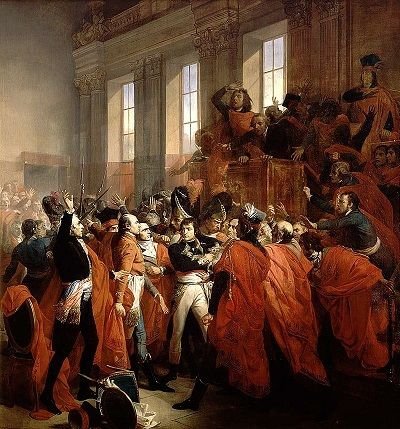

Despite the failures in Egypt, Napoleon returned to a hero's welcome. He drew together an alliance with director Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, his brother Lucien, speaker of the Council of Five Hundred Roger Ducos, director Joseph Fouché, and Talleyrand, and they overthrew the Directory by a coup d'état on 9 November 1799 ("the 18th Brumaire" according to the revolutionary calendar), closing down the council of five hundred. Napoleon became "first consul" for ten years, with two consuls appointed by him who had consultative voices only. His power was confirmed by the new "Constitution of the Year VIII", originally devised by Sieyès to give Napoleon a minor role, but rewritten by Napoleon, and accepted by direct popular vote (3,000,000 in favor, 1,567 opposed). The constitution preserved the appearance of a republic but in reality established a dictatorship.

Invasion of Russia

In 1808, Napoleon and Czar Alexander met at the Congress of Erfurt to preserve the Russo-French alliance. The leaders had a friendly personal relationship after their first meeting at Tilsit in 1807. By 1811, however, tensions had increased and Alexander was under pressure from the Russian nobility to break off the alliance. A major strain on the relationship between the two nations became the regular violations of the Continental System by the Russians, which led Napoleon to threaten Alexander with serious consequences if he formed an alliance with Britain.

By 1812, advisers to Alexander suggested the possibility of an invasion of the French Empire and the recapture of Poland. On receipt of intelligence reports on Russia's war preparations, Napoleon expanded his Grande Armée to more than 450,000 men. He ignored repeated advice against an invasion of the Russian heartland and prepared for an offensive campaign; on 24 June 1812 the invasion commenced.

The Russians avoided Napoleon's objective of a decisive engagement and instead retreated deeper into Russia. A brief attempt at resistance was made at Smolensk in August; the Russians were defeated in a series of battles, and Napoleon resumed his advance. The Russians again avoided battle, although in a few cases this was only achieved because Napoleon uncharacteristically hesitated to attack when the opportunity arose. Owing to the Russian army's scorched earth tactics, the French found it increasingly difficult to forage food for themselves and their horses.

he Russians eventually offered battle outside Moscow on 7 September: the Battle of Borodino resulted in approximately 44,000 Russian and 35,000 French dead, wounded or captured, and may have been the bloodiest day of battle in history up to that point in time. Although the French had won, the Russian army had accepted, and withstood, the major battle Napoleon had hoped would be decisive. Napoleon's own account was: "The most terrible of all my battles was the one before Moscow. The French showed themselves to be worthy of victory, but the Russians showed themselves worthy of being invincible".

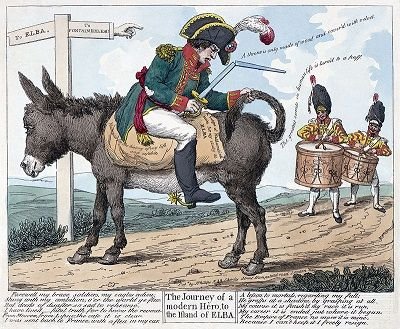

Exile to Elba

In the Treaty of Fontainebleau, the Allies exiled him to Elba, an island of 12,000 inhabitants in the Mediterranean, 20 km (12 mi) off the Tuscan coast. They gave him sovereignty over the island and allowed him to retain the title of Emperor. Napoleon attempted suicide with a pill he had carried after nearly being captured by the Russians during the retreat from Moscow. Its potency had weakened with age, however, and he survived to be exiled while his wife and son took refuge in Austria. In the first few months on Elba he created a small navy and army, developed the iron mines, oversaw the construction of new roads, issued decrees on modern agricultural methods, and overhauled the island's legal and educational system. A few months into his exile, Napoleon learned that his ex-wife Josephine had died in France. He was devastated by the news, locking himself in his room and refusing to leave for two days.

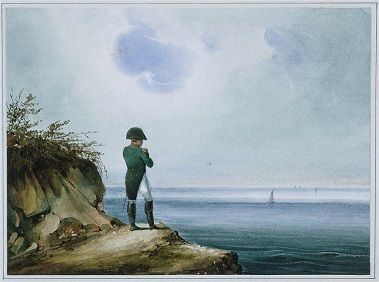

Exile on Saint Helena

Britain kept Napoleon on the island of Saint Helena in the Atlantic Ocean, 1,870 km (1,162 mi) from the west coast of Africa. Napoleon was moved to Longwood House there in December 1815; it had fallen into disrepair, and the location was damp, windswept and unhealthy. The Times published articles insinuating the British government was trying to hasten his death, and he often complained of the living conditions in letters to the governor and his custodian, Hudson Lowe.

With a small cadre of followers, Napoleon dictated his memoirs and grumbled about conditions. Lowe cut Napoleon's expenditure, ruled that no gifts were allowed if they mentioned his imperial status, and made his supporters sign a guarantee they would stay with the prisoner indefinitely.

There were rumors of plots and even of his escape, but in reality no serious attempts were made. For English poet Lord Byron, Napoleon was the epitome of the Romantic hero, the persecuted, lonely, and flawed genius.

Death

In February 1821, Napoleon's health began to deteriorate rapidly. He reconciled with the Catholic Church. He died on 5 May 1821, after confession, Extreme Unction and Viaticum in the presence of Father Ange Vignali. His last words were, "France, l'armée, tête d'armée, Joséphine" ("France, army, head of the army, Joséphine").

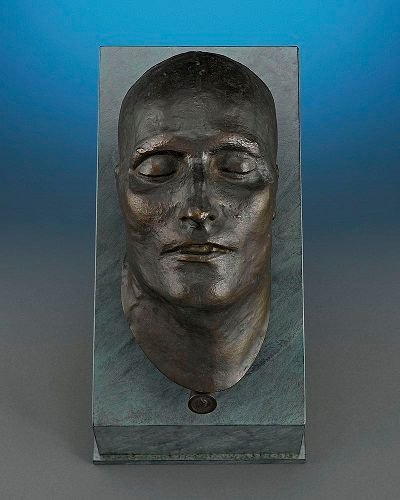

Napoleon's original death mask was created around 6 May, although it is not clear which doctor created it. In his will, he had asked to be buried on the banks of the Seine, but the British governor said he should be buried on Saint Helena, in the Valley of the Willows.

I hope you liked the second article of the "Most Significant Figures in History" about this great person. Note, that the number in the title does NOT mean that the one figure had more influence than the other.

Thank you for reading, I hope you liked it. If you did, consider upvoting and following me. :)

Napoleon in essence was on of the main responsibles for the spread of the french revolutions ideals in all of Europe, many many wars later he lost it all, still history remembers him more than the victors, what a man!

Peace and keep it up, Carlos

Wow. Love this. When my sister and i traveled Europe we were taken to a kind of memkrial of him. I love history and your post is very interesting. I did not realise that he had a death mask and wanted to be buried on the banks of the seine

This post has received a 8.04 % upvote from @booster thanks to: @elephantas1.