Covid-19: French bill could ban unvaccinated from public transport

People who fail to get a Covid-19 vaccination could be banned from using public transport in France, according to a draft law sparking angry protests from opposition politicians on Tuesday.

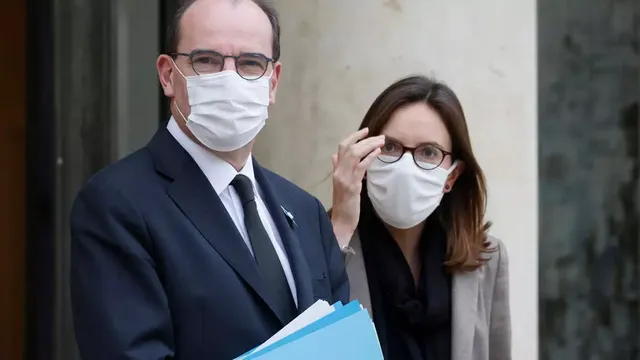

Prime Minister Jean Castex on Monday got his cabinet's backing for a bill that is designed to provide a legal framework for dealing with health crises, including the coronavirus pandemic.

According to the text, which will now be submitted to parliament, a negative Covid test or proof of a "preventative treatment, including the administration of a vaccine" could be required for people to be granted "access to transport or to some locations, as well as certain activities".

According to opinion polls, 55 percent of French people say they will not get a Covid shot, one of the highest rates in the European Union.

The government's vaccination campaign is to start on Sunday.

President Emmanuel Macron has promised that coronavirus vaccinations, though strongly recommended, will not be mandatory.

But opposition politicians condemned the draft law, with Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right RN party, calling it an "essentially totalitarian" measure.

"In a backhanded way, this bill does not aim to make vaccinations mandatory, but will prevent anybody who doesn't comply from having a social life," she said.

RN party spokesman Sebastien Chenu said Macron's government was planning "a health dictatorship".

Guillaume Peltier, deputy leader of the centre-right LR party, said it was "inconceivable" that the government should be allowed to "get all the power to suspend our freedoms without

Centrist senator Nathalie Goulet said the draft was "an attack on public freedoms", while the far-left deputy Alexis Corbiere said "we could at least have a collective discussion if the idea is to limit our public liberties."

In response, public sector minister Amelie de Montchalin said the bill was "not at all made to create exceptional powers for the government" or "create a health state."

She said there would be a debate about the bill during which "everything that needs clarification will be clarified."

WATCH NOW ► https://m.vlive.tv/post/1-20486456

June 2021. The world has been in pandemic mode for a year and a half. The virus continues to spread at a slow burn; intermittent lockdowns are the new normal. An approved vaccine offers six months of protection, but international deal-making has slowed its distribution. An estimated 250 million people have been infected worldwide, and 1.75 million are dead.

Scenarios such as this one imagine how the COVID-19 pandemic might play out1. Around the world, epidemiologists are constructing short- and long-term projections as a way to prepare for, and potentially mitigate, the spread and impact of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Although their forecasts and timelines vary, modellers agree on two things: COVID-19 is here to stay, and the future depends on a lot of unknowns, including whether people develop lasting immunity to the virus, whether seasonality affects its spread, and — perhaps most importantly — the choices made by governments and individuals. “A lot of places are unlocking, and a lot of places aren’t. We don’t really yet know what’s going to happen,” says Rosalind Eggo, an infectious-disease modeller at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM).

WATCH NOW ► https://m.vlive.tv/post/1-20486509

“The future will very much depend on how much social mixing resumes, and what kind of prevention we do,” says Joseph Wu, a disease modeller at the University of Hong Kong. Recent models and evidence from successful lockdowns suggest that behavioural changes can reduce the spread of COVID-19 if most, but not necessarily all, people comply.

Last week, the number of confirmed COVID-19 infections passed 15 million globally, with around 650,000 deaths. Lockdowns are easing in many countries, leading some people to assume that the pandemic is ending, says Yonatan Grad, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts. “But that’s not the case. We’re in for a long haul.”

WATCH NOW ► https://m.vlive.tv/post/0-20479735

If immunity to the virus lasts less than a year, for example, similar to other human coronaviruses in circulation, there could be annual surges in COVID-19 infections through to 2025 and beyond. Here, Nature explores what the science says about the months and years to come.

What happens in the near future?

The pandemic is not playing out in the same way from place to place. Countries such as China, New Zealand and Rwanda have reached a low level of cases — after lockdowns of varying lengths — and are easing restrictions while watching for flare-ups. Elsewhere, such as in the United States and Brazil, cases are rising fast after governments lifted lockdowns quickly or never activated them nationwide.

WATCH NOW ► https://m.vlive.tv/post/1-20486555

The latter group has modellers very worried. In South Africa, which now ranks fifth in the world for total COVID-19 cases, a consortium of modellers estimates2 that the country can expect a peak in August or September, with around one million active cases, and cumulatively as many as 13 million symptomatic cases by early November. In terms of hospital resources, “we’re already breaching capacity in some areas, so I think our best-case scenario is not a good one”, says Juliet Pulliam, director of the South African Centre for Epidemiological Modelling and Analysis at Stellenbosch University.

But there is hopeful news as lockdowns ease. Early evidence suggests that personal behavioural changes, such as hand-washing and wearing masks, are persisting beyond strict lockdown, helping to stem the tide of infections. In a June report3, a team at the MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis at Imperial College London found that among 53 countries beginning to open up, there hasn’t been as large a surge in infections as predicted on the basis of earlier data. “It’s undervalued how much people’s behaviour has changed in terms of masks, hand washing and social distancing. It’s nothing like it used to be,” says Samir Bhatt, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at Imperial College London and a co-author of the study.

WATCH NOW ► https://m.vlive.tv/post/0-20479797

Researchers in virus hotspots have been studying just how helpful these behaviours are. At Anhembi Morumbi University in São Paulo, Brazil, computational biologist Osmar Pinto Neto and colleagues ran more than 250,000 mathematical models of social-distancing strategies described as constant, intermittent or ‘stepping-down’ — with restrictions reduced in stages — alongside behavioural interventions such as mask-wearing and hand washing.

The team concluded that if 50–65% of people are cautious in public, then stepping down social-distancing measures every 80 days could help to prevent further infection peaks over the next two years4. “We’re going to need to change the culture of how we interact with other people,” says Neto. Overall, it’s good news that even without testing or a vaccine, behaviours can make a significant difference in disease transmission, he adds.

WATCH NOW ► https://m.vlive.tv/post/0-20479823

Infectious-disease modeller Jorge Velasco-Hernández at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Juriquilla and colleagues also examined the trade-off between lockdowns and personal protection. They found that if 70% of Mexico’s population committed to personal measures such as hand washing and mask-wearing following voluntary lockdowns that began in late March, then the country’s outbreak would decline after peaking in late May or early June5. However, the government lifted lockdown measures on 1 June and, rather than falling, the high number of weekly COVID-19 deaths plateaued. Velasco-Hernández’s team thinks that two public holidays acted as superspreading events, causing high infection rates right before the government lifted restrictions6.

In regions where COVID-19 seems to be on the decline, researchers say that the best approach is careful surveillance by testing and isolating new cases and tracing their contacts. This is the situation in Hong Kong, for instance. “We are experimenting, making observations and adjusting slowly,” says Wu. He expects that the strategy will prevent a huge resurgence of infections — unless increased air traffic brings a substantial number of imported cases.

WATCH NOW ► https://m.vlive.tv/post/0-20479893

Pandemic on campus: tell us how your institution is coping

But exactly how much contact tracing and isolation is required to contain an outbreak effectively? An analysis7 by the Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group at the LSHTM simulated fresh outbreaks of varying contagiousness, starting from 5, 20 or 40 introduced cases. The team concluded that contact tracing must be rapid and extensive — tracing 80% of contacts within a few days — to control an outbreak. The group is now assessing the effectiveness of digital contact tracing and how long it’s feasible to keep exposed individuals in quarantine, says co-author Eggo. “Finding the balance between what actually is a strategy that people will tolerate, and what strategy will contain an outbreak, is really important.”

Tracing 80% of contacts could be near-impossible to achieve in regions still grappling with thousands of new infections a week — and worse, even the highest case counts are likely to be an underestimate. A June preprint1 from a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) team in Cambridge analysing COVID-19 testing data from 84 countries suggests that global infections were 12 times higher and deaths 50% higher than officially reported (see ‘Predicting cases and deaths’). “There are many more cases out there than the data indicate. As a consequence, there’s higher risk of infection than people may believe there to be,” says John Sterman, co-author of the study and director of the MIT System Dynamics Group.

WATCH NOW ► https://demon-slayer-full-movie-eng-sub.tumblr.com/

For now, mitigation efforts, such as social distancing, need to continue for as long as possible to avert a second major outbreak, says Bhatt. “That is, until the winter months, where things get a bit more dangerous again.”

What will happen when it gets cold?

It is clear now that summer does not uniformly stop the virus, but warm weather might make it easier to contain in temperate regions. In areas that will get colder in the second half of 2020, experts think there is likely to be an increase in transmission.

WATCH NOW ► https://anime-film-demon-slayer-sub-indo.tumblr.com/

Many human respiratory viruses — influenza, other human coronaviruses and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) — follow seasonal oscillations that lead to winter outbreaks, so it is likely that SARS-CoV-2 will follow suit. “I expect SARS-CoV-2 infection rate, and also potentially disease outcome, to be worse in the winter,” says Akiko Iwasaki, an immunobiologist at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Evidence suggests that dry winter air improves the stability and transmission of respiratory viruses8, and respiratory-tract immune defence might be impaired by inhaling dry air, she adds.

In addition, in colder weather people are more likely to stay indoors, where virus transmission through droplets is a bigger risk, says Richard Neher, a computational biologist at the University of Basel in Switzerland. Simulations by Neher’s group show that seasonal variation is likely to affect the virus’s spread and might make containment in the Northern Hemisphere this winter more difficult9.