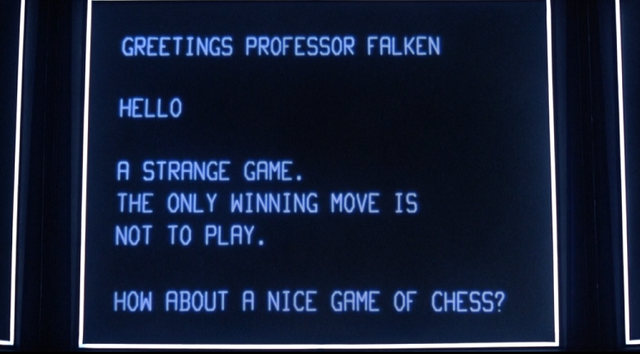

Contemplating life with Zugzwang....A strange game, Dr. Falken....

Do we make a move, give into the compulsion, and play by the rules of the games? Or, should we be anarchists to the game, free ourselves from the limitations of choices and choose to disengage?

The term, Zugzwang, latched into my conscious years ago and has since stuck close to my heart all this time. Though zugzwang hasn’t played any particular role in my philosophical development— aside from being a quality conversation starter— I always had this nagging need to detangle it. Zugzwang means, as defined by the film Mr. Nobody, “when the only viable move…is not to move”. Originally a chess term, it refers to a state within gameplay in which any series of moves would result in a loss. In Mr. Nobody, zugzwang becomes reality as “a nine year old boy faced with an impossible decision” can see the future effect of all possible choices. Yet, even after experiencing all the possible outcomes, he is still unable to dissect the pros and cons of each choice. The narrator states, “Before, he was unable to make a choice because he didn't know what would happen. [But], Now that he knows what will happen, he is unable to make a choice.” Presumably, he is in zugzwang because the only choice he has is to not choose at all, allowing all possible outcomes to remain possible.

Choices give our lives meaning, they narrow down the possibilities of our reality so that we can derive meaning from them.

We can’t give meaning to everything, so we have to choose. For example, if we could be a firefighter, teacher, stockbroker, and philosopher while also marrying our childhood friend, high school sweetheart, and college professor, while also having 3 kids and no kids all at once—who really are we?

We have to choose, escape zugzwang, if we want meaning. We have to play the game, right?

Paradoxically though, regardless of the specific path we take, the mere fact that we are taking a path indicates we will find meaning. If choices, inherently, narrow down our reality so that we can find meaning, then any choice results with meaning… “Every path is the right path. Everything could have been anything else and it would have just as much meaning”...

The meaning we find relies on the connections and patterns we choose to see and create. We are all subject to Skinner’ pigeon superstition creatively used to begin the film. Food is delivered at regular time intervals, but we ask “what did I do to deserve this?” and mistakenly attribute feeding time to certain behaviors. We think that food comes when we pull a string, or chirp, or flap our wings, but in reality, the food is coming either way and we don’t have to do anything at all. We get caught up in all the actions, the choices, the behaviors that yield a certain meaning, but the meaning is always there. Or, perhaps, with the food always being delivered regardless of our actions, with an innate ability to find meaning in everythings, comes the sense that we are meaningless, finding patterns where there are none and having little control over our plight…. In a twist of fate, the capacity for all possible meanings cultivates no meaning at all. We are stuck, yet again, in zugzwang, where it seems the only option is to disengage.

Such post-modernist applications of zugzwang, though entertainingly depressing, limit the full potential of the term. Outside Mr. Nobody’s definition, zugzwang means “compulsion to move”.

.jpg)

We are driven to play by the rules of the game, have a winner and loser, and make the “right” choice. Zugzwang encompasses this compulsion, a state of liminality where we are between not moving and moving, stuck in limbo with an urge to get out in order to maintain the context. This appears indirectly in the famous film, War Games, when WOPR tries to play tic-tac-toe against itself which results in a series of ties. The computer comments “a strange game, Dr. Falken. the only winning move is not to play”. This realization ultimately shuts the computer-generated nuclear warfare down, as the system finally learns the value of futility. The computer had this innate “compulsion” to win the game, but failed to realize that nuclear warfare is an imminent suicide mission. In the end, we were all safer abandoning “the game” itself and staying in zugzwang.

From the nature of reality to computer-generated nuclear warfare, zugzwanging appears immensely impersonal. Can we, as individuals, be in a state of zugzwang that surpasses thought experiments and encompasses our whole being? Let’s narrow it down a bit more.

Psychologists and biologists alike rely on the “fight or flight” analysis of animal behavior. When we face a threat, the logical and evolutionary response requires us to choose; do we fight against this threat, or is it better to flee altogether? Depending on the threat and the victim, one may be more opportune than the other. I may choose to fight my younger brother when provoked, but be more apt to run away from my angry father in a confrontation. Yet, recently, one more response has come up as a possibility: freeze.

Freeze is a complete state of zugzwang, we can’t for sure fight, nor flee with complete certainty, so we just…do nothing.

We have a compulsion to do something, so we use this time of “freeze” to process a bit further. The application is deeper when we integrate freezing with generalized anxiety disorder. When we are uncertain of what the threat is itself, how can we fight or flee? We can’t, so we freeze, hoping for the anxiety to pass. Or, in instances of trauma, we freeze, disengage, and blackout as if to protect ourselves from the experience at all. The only viable, self-perserving, move…is to not move at all.

But, is this really productive? In the case of flight, fight, or freeze, it seems a state of zugzwang is reasonable, if not pertinent. But, what about a perpetual state of zugzwang?

Is not moving still a move? Do we make a move, give into the compulsion, and play by the rules of the game, which may or may not result in undesirable outcomes? Or, should we be anarchists to the game, free ourselves from the limitations of choices and choose to disengage, risking loss of meaning and productivity? It seems that considering zugzwang as a way of life becomes zugzwang in it of itself, a meta-choice in which we ask ourselves, “should it even be a choice at all?”