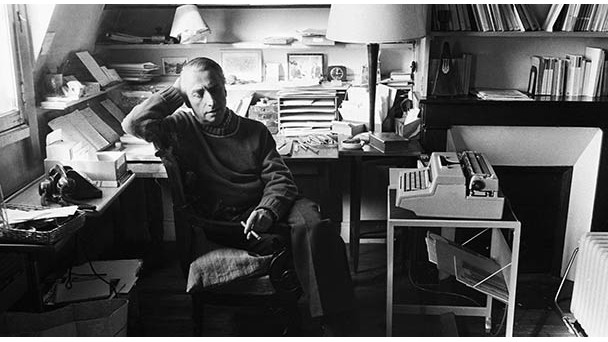

Camera Lucida by Rolland Barthes

Roland Barthes approaches the subject of photography, not through an identification of its different manifestations - the vulgar portrait or landscape characterization, professional or amateur - but rather analyzing the photograph as a whole, designing a method of classification of it, in order to define its essence.

In an initial approach, which the author describes as failing at the end of the first part of the book, he makes a merely personal and, I would say, passionate reflection on the subject. He himself acknowledges that "subjectivity reduced to his hedonistic project could not recognize the Universal". The word passion becomes, presumably, the reason for its error since its evaluation is not exempt, it is an investigation conducted excessively based on what the photograph does to him. However, in taking this risk, Barthes manages to carry us with him in his demand, towards the heart of the photograph.

Through the creation of a terminology as unpublished as appropriate, it makes clear its process of discovery: it designates as "Operator" the photographer, names as "Spectator" the one who sees the image, classifies as "Spectrum" the photographic referent, adopts the “Studium" for the awakening of interest or indifference and finally recognizes the “Punctum" where, incidentally, there is a specific sensation, the wound, the shock, the detail that establishes a direct and immediate relationship with the one who sees the image.

The author argues that photography, unlike other arts, is impervious to signs, to the codes of culture and language. It establishes an interesting analogy between Photography and Death, defending that the photo metamorphoses the being into object. He compares it to the theater over painting: "Photo is like a primitive theater, like a living painting, the figuration of the still and painted face under which we see the dead".

In the second half of the book we see Barthes deepening his analysis while making a tribute to his recently deceased mother.

He now explores deeply the manifestations of his desire, using all that he had uncovered in the first part. From the observation of photographs - whose motto is his own mourning - he discovers in photography the inexorable manifestation of the real: "all photography is a certificate of presence". It also extends its conception of "punctum" to Time, finding in it the "this was" which becomes unmistakably for Barthes the "noema" of Photography, and this, consequently, an indisputable ethnographic object.

Returning to associate Photography and Death, he then establishes a new relationship that he exemplifies better this way: "Before the photo of my mother, child, I say to myself: she is going to die".

He concludes his final work with the glimpse of two possible choices in Photography: the photograph of realism contingent on aesthetic and empirical concerns or a photograph of pure and absolute realism, that which carries with it "the awakening of inaccessible reality".

This work reveals the photo as an object in which one can find an instant of life that brings us to a place between the past and the present, the photographic act as the materialization of death. This concept comes into direct conflict with a notion that was present in me, that of perpetuation through photography; in fact it is common to hear that something or someone was immortalized by the lens of "such" photographer, but what actually happens when I see the last record of a portrait of me is to say "I was like this" or "this was me".

Another question arises when the author defines three practices associated with photography: "do, try, look" (p.23). Dismissing his responsibilities at first - he assumes that he is not a photographer - shows ignorance in one of his facets, and in doing so, in addition to conditioning his own research, seems to me to contradict his overall view of photography. If the demand to see as a whole, without differentiation between those who practice it, one should not put the question of amateurism. Is it possible that a photographer, like Barthes, has never taken a single photo?

What is certain is that in doing so he emphasizes the notion that his study refers to the perspective of the Spectator, not the Operator.

This devaluation of the difference between professional and amateur that the author seeks in his original thesis - see the photograph in its entirety - refers us to a very current reflection: the democratization of labor practices, the increasing competition between professionals and amateurs, the proliferation of creative act provided by the advent of the internet and new digital media.

When we read "nothing can prevent analogue photography", we certainly do not remain impassive in challenging it, even more so with the double meaning that the statement obtains from the instruments known today. The idea that photography always translates the real does not suit today’s reality and I have serious doubts that it has ever done it with absolute rigor. "What was" has never been completely without achievement, there has been manipulation of the image since the beginning of photography.

However, this notion does not devalue Barthes's theory if we understand it from its prism: the definition of the real that it seeks is not only what was there, but also, and fundamentally, what it identifies as being real to itself. Artifice already existed in the time of Nadar who, like Barthes, sought the essence of things, the soul of the portrayed and repudiated the "... retouching, which removes to the face any interior expression and turns it into a vulgar image, too finished and lifeless ... "(Freund 1995: 53). For Barthes, photography happens not when it appears as a recomposition but rather as a confirmation that something existed in fact; or whether it exists or not.

It is inconsequential, therefore, to question whether the author has discovered the "universal" truth of photography. It seems clear to me that he found his own truth, his reality, well illustrated in the example quoted in "Winter Garden Photography," when he finally revisited his newly deceased mother in the midst of so many other photos where, with or without artifacts, he could not see her at all.

Regardless of whether it is infallible or ineffective, I consider Barthes's model of research to be fruitful: it is passionate and in my view passional; is certainly personal and perhaps, therefore, intransmissible. It is certain that the author is able to convey his point of view unequivocally and, in that sense, it is clear to me that his investigation is pertinent. It may be not a universal or timeless definition of Photography, but it is certainly the meaning of Photography for Barthes.

Acquiring philology, I recognize in his work the studium, but what binds me to his narrative is his punctum, the detail materialized through the author's passion for photography, and I therefore cease to see - as he did - it’s universal truth but rather the one conferred by one's own, the detail to which I can not remain indifferent.

I believe photography for him was something else, something very present in his essay. But then again, perhaps photography is no longer death, as Barthes knew it, perhaps it is simply dead .(MIRZOEFF, 1999: 65).