The (Non)Definitive William Blake: Theology and Process in the Illuminated Books & Prophecies (PART 3)

By the time of writing Milton, the very real John Milton was among England’s most celebrated artists, and in Blake’s view superior even to Shakespeare. Milton had been canonized amongst poets, and Paradise Lost was the closest literature had come to scripture, both in intention and execution, since Dante. Milton dramatized the Fall where Genesis falls flat, creating a story much more resonant than the Bible’s stark verse. What the Bible covers in a handful of pages, Milton takes on in twelve books: he humanizes Adam and Even, crafts a Satan with whose motivations the reader can sympathize, and God who feels very human emotions while adhering to the established doctrine of omnipotence and omniscience. Indeed, while Blake adored Milton, his presentation of an inflexible, obstinate power did not sit well with him. Milton, it seemed, had taken on the status of biblical prophet, and thus his words were the unwavering words of God. It is here that Blake identifies one of Milton’s chief mistakes: he has established a restricting, rather than forgiving, institution. Milton takes care to establish Eve’s motivations, expressly establishing the innocence of her intent—while she knows God’s command not to eat the fruit, the serpent manages to convince her otherwise by saying that he himself had eaten, received divine knowledge, and received no punishment. Effectively, Satan convinces Eve that it is God who is the liar, and Eve, in the presence of opposing otherworldly commands, must choose which argument is the more convincing, and she could be forgiven for not knowing which to choose. This is the Beginning, after all, with very little precedent to influence her decision, and the choice she is confronted with two options: believe the voice that made a clear, convincing argument, or believes the voice that merely thundered, “because I said so.” But despite having what this reader considers to be a rather reasonable logic behind her error, God is not so understanding. She and Adam are exiled; because they were deceived, they will have a chance of redemption through toil and obedience. Satan, however, is forever damned. Whereas Adam and Eve erred honestly (well, Eve, anyway), Satan knew exactly what he was doing, and therefore lost any chance of redemption. No amount of contrition or repentance will save Satan’s immortal soul.

This inflexibility is a major error for Blake, who maintains the supremacy of openness and love. While we may understand God’s treatment of Adam and Eve—his punishment is harsh, but they still have a chance of redemption—his treatment of Satan is less savory. Blake recognizes that while Milton provides Satan with a level of humanity that allows us to empathize with him, he denies Satan any rights or dignity associated with humanity. Blake’s Milton will recognize this in the poem’s climax when Milton annihilates his self/Satan by forgiving him. But unfortunately, contemporary readers—and indeed, probably today’s readers—would be hesitant to embrace such an alternative view. Blake’s ideas seemed a danger, even to the mortal soul, when Milton’s God was known to be the truth. It had become, in Coleridge’s words, “so true, that [it loses] all power of truth, and lie bed-ridden in the dormitory of the soul, side by side with the most despised and exploded errors (AR 1). Like those truths distinguished by Coleridge, Milton’s worldview had a wealth of inspired truth to offer, but it had become so commonplace as to warrant the neglect of active reflection. It is interesting that Coleridge chose the word “dormitory” to describe this area of our soul, indicating that he, like Blake, believes that our ability to comprehend real truth is merely sleeping.

Having identified the problem, it is at this point that Blake takes action. He does not mean to debunk Milton as a fraud but recognizes that, despite his greatness, Milton still made mistakes. This first was his spiritual inflexibility, and the second was his treatment of others, particularly his wives and daughters. Blake tried to recognize this error in his own life, at an enlightened moment referring to his own wife, Catherine, as the “sweet Shadow of my Delight, recognizing her as herself a glimpse of Eternity through his willingness to love her as such. Milton, in short, did not live the open, loving life that his Christ extolled.

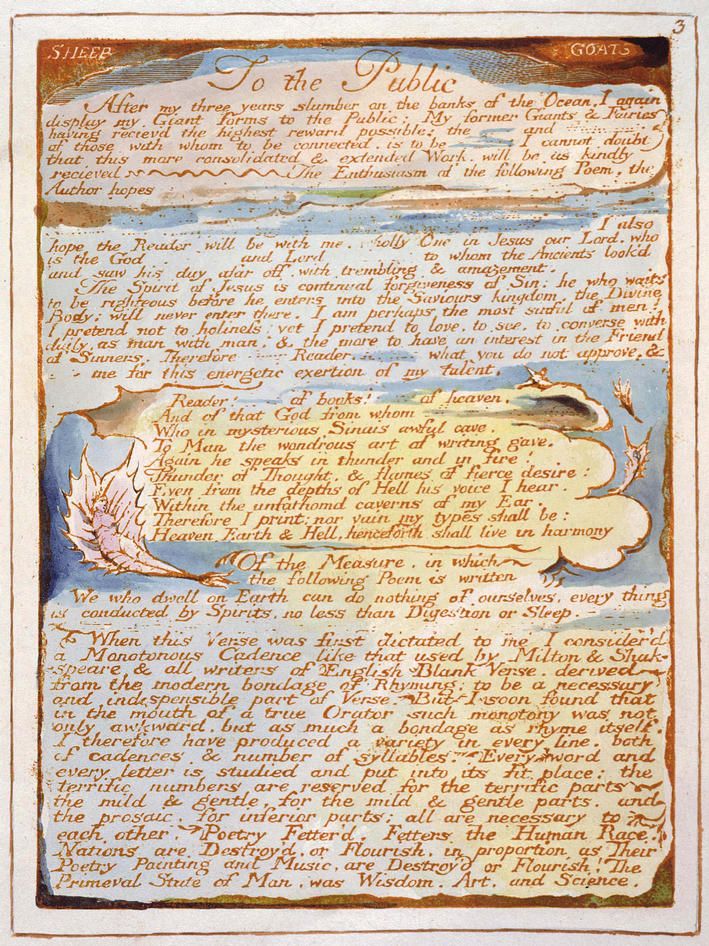

We now come to my final argument, which concerns the reading practices associated with Blake’s prophetic books. Taken as a whole, these books constitute a cosmological theory that Blake held to be a kind of literal truth, and not merely metaphorical representations of psychological states. For Blake, humanity, God, and universe are concurrently in a continual, mutually constitutive state of creation, and so the reading practices associated with these poems should reflect that. Furthermore, Blake certainly hoped for his work to be widely read, even going so far as to open his last great epic, Jerusalem, with a plate titled, “To the Public”:

Figure 1: "To the Public" (J E:3)

But Blake, a printer, would have known that there would not be any possible way for the public to actually read and view his illuminated books. These poems are simply too difficult—the meter will change from line to line, the metaphors are obscure and counterintuitive, the message too radical to fit into comfortable concepts. In any case, these poems are remarkably time-intensive. Imagine reading one of Blake’s original prophecies in a museum or a gallery, and doing so quickly enough for the next patron to do the same! From a logistical standpoint, the very idea is absurd.

And yet, that is precisely what Blake envisioned. The technologies of the early 19th Century could not have handled such a task—there simply could not have been a scenario in which Blake’s illuminated books could have been mass-produced as he intended.

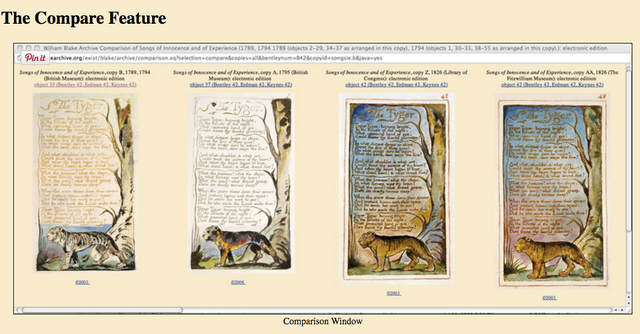

The Internet, though, is as close as we have come to a means of distribution that comports with what Blake envisioned. And certainly, attempts have been made. The William Blake Archive (blakearchive.org) is the most ambitious attempt to date, and the editors have done remarkable work. The Blake Archive offers a comparison feature, whereby any given plate can be viewed alongside the other copies of that plate:

Figure B: Several selections of “The Tyger.” Blake Archive, Sample Comparison Window (http://www.blakearchive.org/blake/help/help.html)

And yet there is more work to be done!

The William Blake Archive is a tremendous achievement, but digital representation is an extraordinarily flexible mode of representation. I conclude this paper with a few thoughts that will inform future projects.

Despite being a burgeoning field, “Digital Humanities” still lacks clear definition. To date, DH has typically adopted quantitative methods to approach humanities in ways that tend to add little beyond what traditional humanities were already capable of. But reading Blake through a digital lens may indeed offer a way of reading them that more closely resembles what Blake might have imagined. As Blake constructed and subsequently published his illuminated books, he would often rearrange plates, make corrections, omit or add passages, etc. Thus there can be no “definitive” text of many of these poems, contrary to standard editorial practices and goals of textual studies. And given Blake’s insistence on subjectivity, imagination, and process it is unlikely that he ever intended for there to be “one” text. Fortunately, there no longer has to be.

Digital representation offers flexible reading paths and robust visualization tools appropriate for such a reading practice. We reinterpret Blake’s work to maximize the potential for flexible, close reading in a new way. Readers may choose between paths for different “readings” of a poem, see where rearrangements were made, trace characters through their story arcs and see where they interact, incorporate critical and biographical data—the options for interpretation are limited only by the imaginations of the scholars committed to the study of Blake. There is but one danger to Blake studies—that he may become static and, therefore, useless. Morris Eaves, drawing from W.J.T. Mitchell’s work, “Dangerous Blake,” remarks thusly: “A Blake who can’t surprise his readers may not be able to hold his place. In the half-decade since Mitchell’s article, though progress has continued, no new era has begun (Damon, XVI).

It is time for such a new era. Blake is dangerous to powers-that-be, and it would be foolish of us to neglect that fact. How we are to understand and read Blake is up for debate, but it cannot be denied that Blake intended for us to read—really read—what he had to say. Considering the sheer variety of technologies that could be used to present his work in potentially infinite ways, Blake only has the potential to become more alive in this century. Imagine, for example, an interactive art installation intended to immerse a spectator within Blake’s very visions—easily feasible through a variety of screens, mirrors, lighting, sound effects, and art direction. It would expensive and impractical (but then, what installation isn’t?), yet the child in me delights in the prospect of whirling through Milton’s vortex or contending with Satan himself in the safety of MOMA.

A musement, perhaps, but musements are like seeds—many of them will lie dead in the earth, but a few of them will take, and slowly they will grow. Blake’s ideas are among the richest in English literature, and to cultivate interest in his work is to cultivate interest in humanity.

Sources:

- Adams, Hazard. “Structure of Myth in the Poetry of William Blake and W.B. Yeats.” PhD diss., University of Washington, 1953.

- Allington, Daniel, Sarah Brouillette and David Golumbia. “Neoliberal Tools (And Archives): A Political History of Digital Humanities.” In The Los Angeles Review of Books. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/neoliberal-tools-archives-political-history-digital-humanities/

*Asimov, Isaac. “The Last Question.” In Nine Tomorrows. Robbinsdale: Fawcett Publications, 1978.

*Ault, Donald. “Re-Visioning William Blake’s The Four Zoas.” ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. Volume 3, issue 2 (2007). Department of English, University of Florida. http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v3_2/ault/.

*Blake, William and Gerald E. Bentley. Vala; Or, The Four Zoas: A Facsimile of the Manuscript, a Transcript of the Poem, and a Study of Its Growth and Significance. Oxford: Clarendon, 1963.

*Blake, William. Blake’s Poetry and Designs: Norton Critical Edition. Edited by John E. Grant and Mary Lynn Johnson. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2007.

*Bowman, Donna. “God for Us: A Process View of the Divine-Human Relationship.” In A Handbook of Process Theology, edited by Jay McDaniel and Donna Bowman, 11 – 24. St. Louis: Chalice Press, 2006.

*Davis, Michael. William Blake: A New Kind of Man. Davis: University of California at Davis Press, 1970. Reprint Davis: University of California at Davis Press, 1977.

*Eaves, Morris, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi, eds. The William Blake Archive. November 1996. Web. http://www.blakearchive.org/

*Erdman, David V. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. New York: Random House, 1965. Revised edition New York: Random House, 1988.

*Feldman, Travis. “The Contexts and Production of William Blake’s The Four Zoas: Towards a Theory of the Manuscript.” PhD diss., University of Washington, 2005.

*Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1947.

*Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, Volumes I-II, “Foundations of the Unity of Science, edited by Otto Neurath, Rudolf Carnap, and Charles Morris. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962. Second edition Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970.

*Lowe, Victor. Understanding Whitehead. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1962.

*McGann, Jerome J. A Critique of Modern Textual Criticism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983. Reprint Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1992.

*Milton, John. Paradise Lost. Edited by Stephen Orgel and Jonathan Goldberg. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

*Mitchell, W.J.T. “Dangerous Blake.” Studies in Romanticism 21 (1982): 410-416.

*Newton, Isaac. Sir Isaac Newton’s Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy and His System of the World. Translated by Andrew Motte, 1729. Edited by Florian Cajori. Berkeley: University of California at Berkeley Press, 1946.

*Pierce, John Benjamin. Flexible Design: Revisionary Poetics in Blake's Vala or the Four Zoas. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1998.

*Plotnitsky, Arkady. “Minute Particulars and Quantum Atoms: The Invisible, the Indivisible, and the Visualizable in William Blake and Niels Bohr.” ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies. Volume 3, issue 2 (2007). Department of English, University of Florida. http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v3_2/plotnitsky/.

*Singer, June K. The Unholy Bible: A Psychological Study of William Blake. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1970. Reprint New York: Harper Colophon, 1973.

*Unger, Roberto Mangabeira and Lee Smolin. The Singular Universe and the Reality of Time: A Proposal in Natural Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

*Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality: An Essay on Cosmology: Gifford Lectures Delivered in the University of Edinburgh During the Session 1927-28. Corrected Edition. Edited by David Ray Griffin and Donald W. Sherburne. New York: The Free Press, 1978.

*Whitehead, Alfred North. Science and the Modern World: Lowell Lectures 1925. New York: The Free Press, 1967.

*Whitson, Roger and Jason Whittaker. William Blake and the Digital Humanities: Collaboration, Participation, and Social Media. New York: Routledge, 2013.

*Wilkie, Brian and Mary Lynn Johnson. Blake’s Four Zoas: The Design of a Dream. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978.

*Wilson, Eric G. My Business Is to Create: Blake’s Infinite Writing. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2011.

*Youngquist, Paul. Madness & Blake’s Myth. University Park: Penn State University Press, 1990.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.