Brazil's Crack Epidemic - Solutions for our Opioid Epidemic Might Just be Across the Hemisphere

While the extremities of drug policy in Latin America are apparent with Uruguay shifting towards a more liberal view, and Peru’s oppressiveness, Brazil can be seen as an intermediary. This country has always been an innovator in public policy, with many countries adopting its way of dealing with the spread of HIV through public programs and campaigns. While we should view Brazil’s drug problem taking into account corruption and social inequality of the country, these problems are faced by a majority of other countries in Latin America on a greater scale. Problems like the culture of favelas, the need for criminal justice reform, organized crime, police brutality, and overpopulation of jails are key points we have to consider to compare how Brazil’s policies put in place can either be adopted or modified to fit our current policies. The two interesting thing to note in Brazil is that many of their policies could be adopted by conservative states if drugs like marijuana were taken of the Controlled Substance list, where they would still be illegal, and also how Brazil is dealing with its crack epidemic, which has stark similarities to the US’s opioid epidemic.

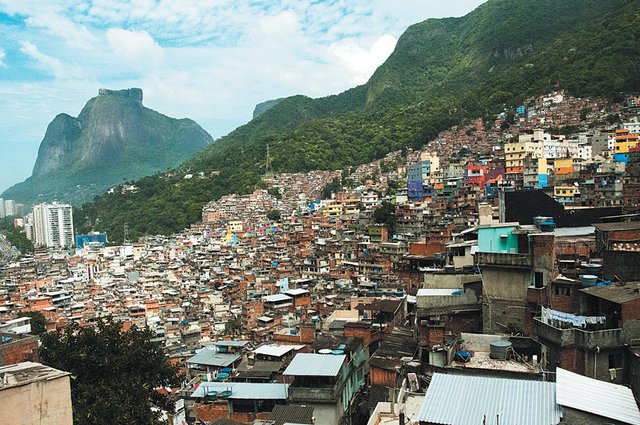

With one of the world's highest high murder rate per capita, coming in at 27.1 murders per 100,000 inhabitants, the Brazilian government has acknowledged that this problem is mostly due crime in terms of narco-trafficking in many urban centers. To understand drug policy and culture in Brazil, we must take into account the social background in low socioeconomic areas. In many cases these problems are concentrated in favelas, communities around big cities like Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo that were caused by the intense industrialization and urbanization of Brazilian society in the earlier part of the 20th century. These communities have learned to cope with the violence in a positive sense with music, like Bezerra da Silva in the 60’s which released satirical music regarding drugs and violence, and today with Brazilian Funk which glorifies drugs, prostitution, and gangs. Samba also originally originated from these communities, with many Schools of Samba that dance in the annual Carnaval parade being predominantly from these communities.

Many building in the favelas are shanty houses built on top of each other on the hills surrounding cities. These communities lack sanitation and safety, often causing deaths during monsoon season because of landslides. Individuals in these communities often have little opportunity for to climb the social ladder, coupled with a lack of proper education they resort to being part of the drug trade, often from a young age by being drug runners or messengers. Criminal organizations in these areas are often divided by what hill a certain favela is on, following an organized hierarchy of drug runners, messengers, soldiers, chiefs, and the drug lord. These drug lords often own territory that can have up to 150 thousand people living in them, financing their operations by buying illegal high caliber weapons often smuggled from countries like Paraguay and Bolivia. While these communities are breeding ground for violence, a big part of the conflict is between criminal organizations trying to expand their influence by invading other favelas, or shootouts with police, both often involve innocent individuals in the crossfire by stray bullets or police brutality. Besides these facts, many people in Brazil consider favelas to be one of the safest places to be because of criminal organizations not tolerating crime by other individuals on their territory, and often times if someone of a higher socio-economic class wished to buy drugs, they often go to the favelas to purchase these drugs, making them drug hubs for the entire city.

The government of Brazil has done a lot to combat the problems of favelas in a two way approach, by granting the populace of these favelas with subsidized housing outside these communities, as well as offering them welfare, but also through specialized police programs to target the criminal organizations like Unidade de Policia Pacificadora (UPP). These examples could be used in the US, not only to reduce drug crime, but the examples of the UPP could also be used to lower the current racial tensions of today's current police force with the violence against African Americans in low income areas. The UPP is a police force of young police officers trains specifically for combating drug violence in favelas that are installed in favelas and maintain 24 hour surveillance of the community. These police detachments are offer incentive pay and are often recruited from the communities they are serving in. Because of this they often have personal ties to the people that live in their favelas, offering a greater cooperation of the people that reside in these areas. Offering an alternative to the harsh treatment usually practiced by police and special forces when they “invade” these favelas causing massive shootouts. This offers the a different style of policing that the federal or state government could use to target specific cities in the US that suffer from high murder rates like communities surrounding Detroit, or Chicago.

While the UPP has shown tremendous improvement by lowering murder rates in favelas, they are only located in small to medium sized favelas, and only in a select number of these. Most citizens of favelas are constantly harassed by police officials and the victims of police brutality. With a “mao dura”, or closed fist approach to policing, they usually resort to “shoot first, ask questions later” policy that puts them in one of the biggest countries where police kill civilians. Most of these killings are extrajudicial, often times with execution type techniques, with little punishment towards the officers that kill individuals. These usually involve cover ups backed by the police departments and state officials. The reason behind this can be explained by the continued violence used by the police since its military government in the later half of the 20th century, a regime put in place and backed by the US’s operation Uncle Sam in 1964. During the military regime, they violently put down protests and persecuted democratic and communist sympathisers with brute force and torture. This did does not only explain current police tactics in Brazil, but also gave way to prominent criminal organizations that flood Brazil’s overcrowded prisons.

Prison overpopulation continues to be a tremendous problem in Brazil due to repeated violence inside the prisons by both guard and inmates, and its effect as a recruiting ground for non-violent drug offenders. The result of this overpopulation stems from the imprisonment of drug related crimes, and also a slow and bureaucratic criminal justice system. With one of the world's largest prison population, over 40% of these inmates are simply waiting for conviction sentencing, which can take months to years because of Brazil's bureaucratic criminal justice system. Prison population in Brazil is mostly made up of young, poor, black Brazilians that have very little opportunities due to living in marginal areas. These are mostly first time offenders without criminal organization ties that are caught selling small amounts of drugs. To understand the consequences of the countries overpopulation, we must analyse the effect of criminal organizations and how they are affected by the current policies of Brazil.

Due to a continued crackdown on drug-related offenses, often a result of police invading favelas, many non-violent drug offenders that come from these areas are put in overcrowded prisons that serve as a recruitment ground for criminal organizations. The largest of these organizations is Command Vermelho (Red Command). What is important to understand is that this group was made of communist sympathisers that were imprisoned during the military dictatorship that lasted from 1964-1985. While they engage in narco-trafficking, and arms smuggling, their political motives are better prison infrastructure and criminal justice reform. This explains the Red Commands slogan of liberty, justice, and peace. The disorganized prison system of Brazil allows these criminal organizations to be imprisoned with no separation between gangs, causing them to recruit new inmates to bolster their members in case of inter-gang fights in prison. Inside these prisons there is very little surveillance, with many inmates being able to smuggle in drugs, and cell phones. This allows them to continue to communicate with the outside and continue their illicit operations, as well as gain information about conflicts regarding these organizations that lead to murders and massacres inside prisons. It is also common for gangs to take over prisons with riots, this causes massacres of rival gang members and prison employees. Because of the mismanagement of prisons in Brazil, there has been severe backlash against the the governmental and private penitentiary industry due to the human rights violations that occur in them. While government policy dictates how these prisons are run, often times due to corruption funds that are designed to maintain and expand these prisons often times go “missing”, causing lack of funding for rehabilitation programs through education, but also for health services. Administrators are also bribed by criminal organizations to look the other way when inmate's murder rival gang members, or smuggle in cell phones and drugs.

While drugs are still illegal in Brazil, the government acknowledges that its past policies of repression against users with jail sentences have not worked. Since 2006, many drug cases are either classified as either personal use or drug trafficking in determining sentencing. There is no threshold in what is considered personal use in a written form, but the decision is decided by the judge that oversees the case. While this might help a majority of Brazilians in avoiding jail time, most of the victims of Brazil's policy of giving authority to judges in determining the the difference can lead to different sentencing to socioeconomic members of society as compared to high income individuals, putting a spotlight on how income equality in Brazil can also be seen in its drug policy.

If the judge determines that the use of the drug was for personal use, the individual is first given a warning, but a second offense requires them to complete community service and enroll in Psico-social centers of attention, known as CAP’s in Brazil. These CAP centers are located nationally around Brazil, and can be found even in rural areas of Brazil. Here drug users around the region come together to talk about experiences, and are taught the consequences of drug and alcohol abuse by trained psychologists for a period of up to 14 days. The intent of these programs are to have the individual that goes through the program to return to society as productive members of society. While people convicted of drugs for personal possessions are required to attend these centers, addicts in the community can also take advantage of these centers and stay there to deal with their drug addiction. These services are completely free, financed by the Ministry of Health.

This system of viewing the solution of drug use through treatment could be used by more conservative states where they would pass state legislation against the legalization and decriminalization of drugs. By advocating the treatment of drug abuse through educational and rehabilitation programs, coupled with community service, they can still combat the use of drugs in their communities without proposing oppressive measures that cause incarceration. It also benefits low income individuals that would not have the resources to find help in private rehabilitation centers, instead opting for public health services that are required for them to attend if they are convicted of possession of small amounts of any drug.

In addition to drug related problems involving trafficking and organized crime, a major problem in Brazilian society today is crack. The drug has made Brazil become the world's largest crack-cocaine consumer, surpassing the US. It has been declared by officials in the country as an epidemic that threatens Brazilian society, and an entire community of crack users have settled in a location in Sao Paulo that is commonly known as “Crackland”, where thousands of people get together and openly use the drug. Crack addicts in these areas are usually homeless, although most have some sort of technical experience like metallurgy, but got sucked into drugs after the financial collapse of 2008. The drug is sold at a very cheap price to these individuals and has created Crackland into a community of homeless drug addicts that continually get harassed by police. Brazilian policy makers and religious entities have made combating the crack epidemic their top priority, and many of their programs have proven to be successful. These programs can be altered and used here in the US to combat our current opioid epidemic due to their low cost and positive effect.

Sao Paulo officials created a program called Sao Paulo with Open Arms to focus on rehabilitation for crack addicts, mostly located in Crackland. The program consists of paying addicts 5 dollars a day for them to work in various city jobs like sweeping streets, or janitorial services in government buildings. In addition to these jobs, they are offered a place to stay, usually a hotel, and 3 meals a day. This program has been incredibly efficient with over 88% of addicts reporting none, or less use of the drug after they have gone through. While this program has been considered a success, policy makers in Brazil are trying to pass new programs like this on a national level with the inclusion of living in rehabilitation centers instead of hotels.

Another program that the federal government is experiment with would be the creation of various “Points of Reception” that would work similarly to what syringe centers would be here in the US. At these locations, drug users can come and take baths, eat food, and rest. Also there would be social workers that would help educate the user on programs that would end their addiction, offering them an environment where they feel comfortable talking about their problems and asking for help. This is a relatively new program that brings up the same problems that lawmakers thing the adoption of syringe centers would bring to the US. While drawing praise from supporters of the program in maintaining a safe environment for drug users, opponents say these centers could become hubs for selling and distributing crack.

These programs coupled with CAP centers in Brazil show us that the government is being proactive in creating a policy that limits the amount of people incarcerated, while at at the same time rehabilitating these individuals to become productive members of society through a safe learning environment, not by throwing them in prison where they are exposed to even more violence. These programs could work in the US if lawmakers are ready to combat the War on Drugs in a different approach than what they are currently doing