African American Voters are Not a Monolith, Neither are America's Rural Voters

What images come to mind when you think about American rural voters? Probably something like this?

While some rural voters do look exactly like the picture described above, most don’t. More than half are women. Many don’t support former president Donald Trump. And most importantly, millions of these rural voters are people of color. Some of these are Native Americans still living on ancestral homelands. Others are Hispanic populations who have also lived in the States for generations and work on farms in the Great Plains. But in the South, there’s an especially unique concentration of African Americans living in rural areas, largely due to our nation’s history of slavery.

A major reason behind the stereotype that rural voters = white voters has to do with the way we present the history of the Great Migration. Following the abolition of slavery, millions of freed African Americans traveled to northern states for better opportunities. While this exodus was incredibly transformational for our country, there were millions of African Americans that stayed in their rural communities in the South.

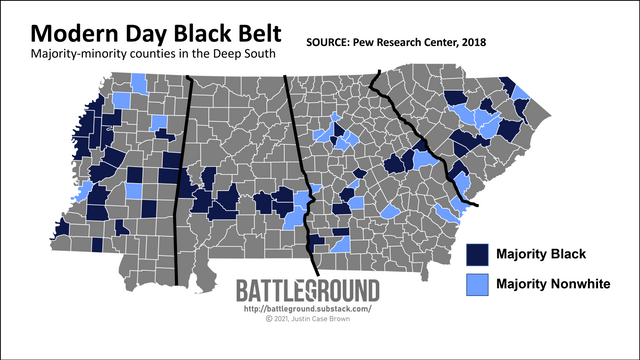

Today, there are 45 counties in the Deep South where African Americans make-up the majority of residents. This region is often called the Black Belt: primarily due to the color of its fertile soil which made the land perfect for slave-owning plantations. Another 25 counties in this area are “minority-majority,” counties where nonwhite residents outnumber White residents. Altogether, voters in these diverse rural areas cast over 3 million votes in the 2020 presidential election.

But this unique coalition of voters is regularly erased from our national consciousness because it fails to conform to how the national Republican and Democratic parties approach the electorate. Democrats have leaned into organizing primarily in urban and suburban areas where social liberalism is thriving. Meanwhile Republicans have tilted further and further toward relying exclusively on White voters who tend to be much more conservative and religious, most of whom live in rural areas. As a result nonwhite rural voters are regularly left out in the cold, ignored by Democrats focused on cities hundreds of miles away and under-served by Republicans focused on appealing to their current base rather than inviting newcomers.

Representation for these communities remains elusive. Mississippi has the country’s largest concentration of African Americans (38% of the state’s residents identify as Black) yet the state has not elected a Black person to any statewide office in the last 100 years. Between Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina, all four of these states are lacking in African American representation on state legislatures. Georgia comes closest to fair representation but, across the board, political leadership is significantly Whiter than the populations they represent. To make matters worse, state parties often refuse to acknowledge these issues; both Democrats and Republicans in the South focus their resources on appealing to White voters rather than attempting to build a more diverse coalition that resembles their entire community.

So how do we change this? We can start by acknowledging that many of the issues rural voters of color face overlap concerns from voters in both parties. Wealth inequality falls starkly along racial lines in these areas. Many of the Black Belt’s counties are also “persistently poor counties,” areas that have retained a poverty rate of at least 20% since 1980. Educational attainment is low in the Black Belt and those that seek out better opportunities are forced to leave the region, leading to a phenomenon known as ‘brain drain.’ Access to healthcare is difficult to say the least, the concentration of hospitals is abysmally low in the region, forcing residents to travel long distances to receive care. (Then when they actually get to the hospital, they typically can’t afford to pay for the care that they need.) Internet access is frustratingly low compared to the rest of the United States. The pandemic underscored the desperate need for a national plan to expand rural broadband as many students were forced to sit in parking lots just to receive a connection strong enough to attend virtual classes.

The more consequential change that’s needed is a shift in political organizing. As of now, many groups simply don’t perform outreach in rural areas, not only because they don’t understand the value, but also because organizing in these areas is more difficult due to the lower population density. Instead of re-inventing the wheel, we should lift up organizations that have already produced success but don’t have the resources to scale up. That includes groups like the Southern Rural Black Women’s Initiative and the Black Farmers and Agriculturalists’ Association.

Everyday our country is growing more diverse and this trend isn’t confined to urban areas. Much of our nation’s rural heartland has been settled by minority groups for generations, it’s time we give them the representation they deserve.

(This piece is a taste of the work I do on the daily for my map-based political newsletter Battleground. I focus on individual states and dive into their political history to explain today's electoral landscape. Be sure to check out more at battleground.substack.com!)