The Social Democratic Case Against Anarchism

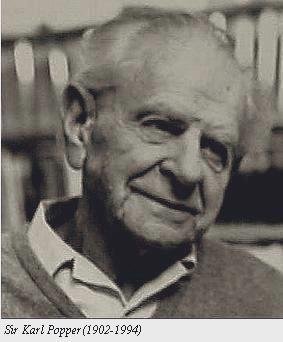

I have rejected anarchism in favor of social democracy. I want to share a few of the social democratic arguments against anarchism. I do this not to argue against anarchism as much as to argue that social democracy is not a complete departure from anarchist principles. The sources that I will be drawing upon are George Bernard Shaw’s The Impossibilities of Anarchism, William Morris’ Socialism and Anarchism, and Karl Popper’s The Open Society and Its Enemies. Shaw and Morris were socialists from an era when socialism and social democracy weren't yet entirely two distinct movements. Popper, on the other hand, was a social democrat in the modern sense, someone who advocates private ownership and a market for the distribution of goods and services but also wants the government to protect the economically weak from those who are economically strong. For the record, I am a social democrat in this more modern sense, with Rawlsian, Georgist, and civic republican leanings.

William Morris makes the case that using collective force in order to protect the rights of individuals is justified. When people come together collectively in order to control the unacceptable behavior of aggressors, they are governing them. This sort of governing is not necessarily incompatible with anarchism. Furthermore, Morris asserts that sometimes collective action must be taken by the community, and collective action has to take place via democratic consensus. Even in the instance of directly defending a person from physical assault—if collective intervention is required—, rules of engagement must be established through a democratic process. People may naturally disagree on how much force is justified in response to a particular form of aggression. If somebody steals fruit from a garden, can you tackle them and slit their throat? Democracy is necessary in order to establish the rules in the first place—how much force is justified in different situations—and in order to establish what actions ought to be taken to deal with the person who uses excessive force against criminals and thereby becomes a criminal as well.

“And here I join issue with our Anarchist-Communist friends, who are somewhat authoritative on the matter of authority, and not a little vague also. For if freedom from authority means the assertion of the advisability or possibility of an individual man doing what he pleases always and under all circumstances, this is an absolute negation of society, and makes Communism as the highest expression of society impossible; but when you begin to qualify this assertion of the right to do as you please by adding ‘as long as you don't interfere with other people's rights to do the same,’ the exercise of some kind of authority becomes necessary. If individuals are not to coerce others, there must somewhere be an authority which is prepared to coerce them not to coerce; and that authority must clearly be collective. And there are other difficulties besides this crudest and most obvious one.

“The bond of Communistic society will be voluntary in the sense that all people will agree in its broad principles when it is fairly established, and will trust to it as affording mankind the best kind of life possible. But while we are advocating equality of condition—i.e., due opportunity free to everyone for the satisfaction of his needs—do not let us forget the necessary (and beneficent) variety of temperament, capacity and desires which exists amongst men about everything outside the region of the merest necessaries; and though many, or, if you will, most of these different desires could be satisfied without the individual clashing with collective society, some of them could not be. Any community conceivable will sometimes determine on collective action which, without being in itself immoral or oppressive, would give pain to some of its members; and what is to be done then if it happens to be a piece of business which must be either done or left alone? would the small minority have to give way or the large majority?... So that it is not unlikely that the public opinion of a community would be in favour of cutting down all the timber in England, and turning the country into a big Bonanza farm or a market-garden under glass. And in such a case what could we do? who objected ‘for the sake of life to cast away the reasons for living,’ when we had exhausted our powers of argument? Clearly we should have to submit to authority. And a little reflection will show us many such cases in which the collective authority will weigh down individual opposition, however, reasonable, without a hope for its being able to assert itself immediately; in such matters there must be give and take: and the objectors would have to give up the lesser for the greater. In short, experience shows us that wherever a dozen thoughtful men shall meet together there will be twelve different opinions on any subject which is not a dry matter of fact (and often on that too); and if those twelve men want to act together, there must be give and take between them, and they must agree on some common rule of conduct to act as a bond between them, or leave their business undone. And what is this common bond but authority—that is, the conscience of the association voluntarily accepted in the first instance….

“Now I don't want to be misunderstood. I am not pleading for any form of arbitrary or unreasonable authority, but for a public conscience as a rule of action: and by all means let us have the least possible exercise of authority. I suspect that many of our Communist-Anarchist friends do really mean that, when they pronounce against all authority. And with equality of condition assured for all men, and our ethics based on reason, I cannot think that we need fear the growth of a new authority taking the place of the one which we should have destroyed, and which we must remember is based on the assumption that equality is impossible and that slavery is an essential condition of human society. By the time it is assumed that all men's needs must be satisfied according [to] the measure of the common wealth, what may be called the political side of the question would take care of itself. ”—William Morris (Socialism and Anarchism)

William Morris, as a democratic socialist, argued that socialism will bring about social equality and eliminate class structures, so that hierarchies and the domination of man over man will be eliminated. Thus, democratic socialism actually tends to be libertarian, so that the schism between libertarian socialism and democratic socialism amounts largely to semantics and point of emphasis. If the extremes of inequality are eliminated, so that there are no really wealthy people or really poor people, then no one will have the economic power that allows one man to dominate others.

George Bernard Shaw makes some of the same points. He, however, delves more deeply into the philosophy of anarchism in his essay The Impossibilities of Anarchism. Shaw starts by declaring that social democrats and anarchists are in total agreement when it comes to their aims and their principles. Shaw and Morris both advocate communism as an end goal. Shaw argues that if there is to be common property, it must be managed by the community, which requires democratic governance. You can't exercise communal ownership by any means other than democracy. If the communist anarchist wants to democratically govern the commons, using direct democracy or consensus processes, then communist anarchism is merely a libertarian variety of democratic socialism—the difference between anarchism and democratic socialism is, again, a matter of semantics and point of emphasis. Furthermore, Shaw argues that the tyranny of the majority is still unavoidable even within anarchism. The anarchist theorist Murray Bookchin disliked consensus processes for this very reason. If the majority wishes to oppress the minority, no political structure or lack of political structure will be able to restrain them. Furthermore, Shaw observes that respectable anarchists like Bakunin and Kropotkin actually advocate delegative democracy, which means that the difference between anarchism and democratic socialism really is semantic. What real difference exists between the libertarian socialism of Peter Kropotkin and the democratic socialism of George Bernard Shaw is a matter of degree—they are different points on the same socialist spectrum. Anarchists will be more explicit and vocal in their critique of hierarchy, but practical application of anarchism always amount to some form of democracy.

“[O]nly specialists in sociology are conscious of the numerous instances in which we are to-day forced to adopt [communism] by the very absurdity of the alternative. Most people will tell you that Communism is known only in this country as a visionary project advocated by a handful of amiable cranks. Then they will stroll off across the common bridge, along the common embankment, by the light of the common gas lamp shining alike on the just and the unjust, up the common street, and into the common Trafalgar Square, where, on the smallest hint on their part that Communism is to be tolerated for an instant in a civilized country, they will be handily bludgeoned by the common policeman, and hauled off to the common gaol. When you suggest to these people that the application of Communism to the bread supply is only an extension, involving no new principle, of its application to street lighting, they are bewildered. Instead of picturing the Communist man going to the common store, and thence taking his bread home with him, they instinctively imagine him bursting obstreperously into his neighbor's house and snatching the bread off his table on the ‘as much mine as yours’ principle—which, however, has an equally sharp edge for the thief's throat in the form ‘as much yours as mine.’ In fact, the average Englishman is only capable of understanding Communism when it is explained as a state of things under which everything is paid for out of the taxes, and taxes are paid in labor….

“Now a Communist Anarchist may demur to such a definition of Communism as I have just given; for it is evident that if there are to be taxes, there must be some authority to collect those taxes. I will not insist on the odious word taxes; but I submit that if any article—bread, for instance—be communized, by which I mean that there shall be public stores of bread, sufficient to satisfy everybody, to which all may come and take what they need without question or payment, wheat must be grown, mills must grind, and bakers must sweat daily in order to keep up the supply. Obviously, therefore, the common bread store will become bankrupt unless every consumer of the bread contributes to its support as much labor as the bread he consumes costs to produce. Communism or no Communism, he must pay or else leave somebody else to pay for him. Communism will cheapen bread for him—will save him the cost of scales and weights, coin, book-keepers, counter-hands, policemen, and other expenses of private property; but it will not do away with the cost of the bread and the store. Now supposing that voluntary co-operation and public spirit prove equal to the task of elaborately organizing the farming, milling and baking industries for the production of bread, how will these voluntary co-operators recover the cost of their operations from the public who are to consume their bread? If they are given powers to collect the cost from the public, and to enforce their demands by punishing non-payers for their dishonesty, then they at once become a State department levying a tax for public purposes; and the Communism of the bread supply becomes no more Anarchistic than our present Communistic supply of street lighting is Anarchistic. Unless the taxation is voluntary—unless the bread consumer is free to refuse payment without incurring any penalty….

“It would take an extraordinary course of demolition, reconstruction, and landscape gardening to make every dwelling house in London as desirable as a house in Park Lane, or facing Regent's Park, or overlooking the Embankment Gardens. And since everybody cannot be accommodated there, the exceptionally favored persons who occupy those sites will certainly be expected to render an equivalent for their privilege to those whom they exclude. Without this there would evidently be no true socialization of the habitation of London. This means, in practice, that a public department must let the houses out to the highest bidders, and collect the rents for public purposes. Such a department can hardly be called Anarchistic, however democratic it may be….

“The majority cannot help its tyranny even if it would. The giant Winkelmeier must have found our doorways inconvenient, just as men of five feet or less find the slope of the floor in a theatre not sufficiently steep to enable them to see over the heads of those in front. But whilst the average height of a man is 5ft. 8in. there is no redress for such grievances. Builders will accommodate doors and floors to the majority, and not to the minority. For since either the majority or the minority must be incommoded, evidently the more powerful must have its way. There may be no indisputable reason why it ought not; and any clever Tory can give excellent reasons why it ought not; but the fact remains that it will, whether it ought or not. And this is what really settles the question as between democratic majorities and minorities. Where their interests conflict, the weaker side must go to the wall, because, as the evil involved is no greater than that of the stronger going to the wall, the majority is not restrained by any scruple from compelling the weaker to give way.

“In practice, this does not involve either the absolute power of majorities, or ‘the infallibility of the odd man.’ There are some matters in which the course preferred by the minority in no way obstructs that preferred by the majority. There are many more in which the obstruction is easier to bear than the cost of suppressing it. For it costs something to suppress even a minority of one….

“In short, then, Democracy does not give majorities absolute power, nor does it enable them to reduce minorities to ciphers. Such limited power of coercing minorities as majorities must possess, is not given to them by Democracy any more than it can be taken away from them by Anarchism. A couple of men are stronger than one: that is all. There are only two ways of neutralizing this natural fact. One is to convince men of the immorality of abusing the majority power, and then to make them moral enough to refrain from doing it on that account. The other is to realize Lytton's fancy of vril by inventing a means by which each individual will be able to destroy all his fellows with a flash of thought, so that the majority may have as much reason to fear the individual as he to fear the majority. No method of doing either is to be found in Individualist or Communist Anarchism: consequently these systems, as far as the evils of majority tyranny are concerned, are no better than the Social-Democratic program of adult suffrage with maintenance of representatives and payment of polling expenses from public funds—faulty devices enough, no doubt, but capable of accomplishing all that is humanly possible at present to make the State representative of the nation; to make the administration trustworthy; and to secure the utmost power to each individual and consequently to minorities. What better can we have whilst collective action is inevitable? Indeed, in the mouths of the really able Anarchists, Anarchism means simply the utmost attainable thoroughness of Democracy. Kropotkine, for example, speaks of free development from the simple to the composite by ‘the free union of free groups’; and his illustrations are ‘the societies for study, for commerce, for pleasure and recreation’ which have sprung up to meet the varied requirements of the individual of our age. But in every one of these societies there is government by a council elected annually by a majority of voters; so that Kropotkine is not at all afraid of the democratic machinery and the majority power. Mr. Tucker speaks of ‘voluntary association,’ but gives no illustrations, and indeed avows that ‘Anarchists are simply unterrified Jeffersonian Democrats.’ He says, indeed, that ‘if the individual has a right to govern himself, all external government is tyranny’; but if governing oneself means doing what one pleases without regard to the interests of neighbors, then the individual has flatly no such right. If he has no such right, the interference of his neighbors to make him behave socially, though it is ‘external government,’ is not tyranny; and even if it were they would not refrain from it on that account. On the other hand, if governing oneself means compelling oneself to act with a due regard to the interests of the neighbors, then it is a right which men are proved incapable of exercising without external government. Either way, the phrase comes to nothing; for it would be easy to show by a little play upon it, either that altruism is really external government or that democratic State authority is really self-government….

“But it is the aim of Social-Democracy to relieve these fools by throwing on all an equal share in the inevitable labor imposed by the eternal tyranny of Nature, and so secure to every individual no less than his equal quota of the nation's product in return for no more than his equal quota of the nation's labor. These are the best terms humanity can make with its tyrant….

“We have seen that the delegation of individual powers by voting; the creation of authoritative public bodies; the supremacy of the majority in the last resort; and the establishment and even endowment, either directly and officially or indirectly and unconsciously, of conventional forms of practice in religion, medicine, education, food, clothing, and criminal law, are, whether they be evils or not, inherent in society itself, and must be submitted to with the help of such protection against their abuse as democratic institutions more than any others afford. When Democracy fails, there is no antidote for intolerance save the spread of better sense. No form of Anarchism yet suggested provides any escape. Like bad weather in winter, intolerance does much mischief; but as, when we have done our best in the way of overcoats, umbrellas, and good fires, we have to put up with the winter; so, when we have done our best in the way of Democracy, decentralization, and the like, we must put up with the State….

“But Kropotkine, as I have shewn, is really an advocate of free Democracy; and I venture to suggest that he describes himself as an Anarchist rather from the point of view of the Russian recoiling from a despotism compared to which Democracy seems to be no government at all….”—George Bernard Shaw (The Impossibilities of Anarchism)

There is a recent trend among communist anarchists to denounce democracy altogether. Whereas classical anarchists tended to equate direct democracy and consensus with anarchism, many modern anarchists reject this approach. It seems to me that this anti-democracy anarchism is self-contradictory when it simultaneously asserts that it is communist. In principle, they are individualists. Communities are not arbitrary. They are made up of definite groups of people—groups that must come to some sort of democratic consensus if they are to manage resources communally. You cannot allow pure autonomy and free association and still have communism. Suppose two separate free associations claim the right to manage the same resources, and each wants to use those resources for different purposes. Their differences can be resolved through force or through democracy. We would need an overarching democratic framework within which to resolve such conflicts. Individualist anarchists have advocated private courts or tribunals and private police forces as a way of resolving disputes, but communists cannot get on board with such proposals. The communist anarchists are in a curious position: if they want to maintain the position that anarchism and democracy are incompatible, they must either give up their claim to communism or their claim to anarchism. The impossibility of anarchism has always been in reconciling its idealistic notion of pure autonomy and absolute free association with this communalist tendency that cries out for democracy.

William Morris and George Bernard Shaw effectively argue that we need democracy and government. Karl Popper makes the case that government ought not to be minimalist. The government ought to do more than just protect people from direct physical aggression: it ought also to protect them from indirect aggression that results from inequality.

"Nobody should be at the mercy of others, but all should have a right to be protected by the state.

"Now I believe that these considerations, originally meant to apply to the realm of brute-force, of physical intimidation, must be applied to the economic realm also. Even if the state protects its citizens from being bullied by physical violence (as it does, in principle under the system of unrestrained capitalism [other editions read "laissez-faire state" in place of "unrestrained capitalism"]), it may defeat our ends by its failure to protect them from the misuse of economic power. In such a state, the economically strong is still free to bully one who is economically weak….

"We must construct social institutions, enforced by the power of the state, for the protection of the economically weak from the economically strong. The state must see to it that nobody need enter into an inequitable arrangement out of fear of starvation, or economic ruin.

"This, of course, means that the principle of non-intervention, of an unrestrained economic system [other editions read "of laissez-faire" in place of "of non-intervention...economic system"] has to be given up; if we wish freedom to be safeguarded, then we must demand that the policy of unlimited economic freedom be replaced by the planned economic intervention of the state."–Karl Popper (The Open Society and Its Enemies, Ch. 17)

Popper's argument is that government ought to protect people from indirect aggression (exploitation) as well as from direct aggression. This makes the case for something far beyond a minarchist night watchman State. Instead of just existing to protect persons and property, the State ought to have a more active role in regulating the economy and human behavior.

Shaw's comments on the tyranny of the majority reminded me of the Paradox of Tolerance. As a whole, great article.

Would love to chat sometime about theory and practical applications. I've been following a few projects lately such as democracy.earth which is building a liquid democracy platform, and while not all of the pieces are yet in place, I have hope that the tools for ethical social shifts are being developed. However, these tools require a strong philosophic if they are to succeed.

Nice articale and I agree with you. I am impressed from your writting skills

So here is my two cents, as an anarchocaptialist.

This article should probably be re-titled as "the Social Democratic Case against Anarchocommunism" because that is consistent with the messaging and content, and it would then be technically true (the best kind of true). However, anarchocommunism is not the only flavour of anarchism, and as such, to only discuss anarchism in terms that the communists use is illogical (composition fallacy) and a massive oversimplification of the term "anarchy".

Voluntaryists such as myself are in favour of a entirely decentralised society, one where as few as possible points of centralisation exist. We also know the value of capitalism & voluntary hierarchies as a solution to societal issues, and recognise the failures placed at capitalism's feet are largely due to government policies creating unintended market consequences.

I note that @ekklesiagora mentioned:

My rebuttal to this is simple: How can a state police service (South Africa) be an example of decentralisation? What is being describe is a less free state being compared with a marginally more free state, but it is not an anarchistic policing solution, and especially not a voluntaryist one. At best this is a strawman argument, unless some evidence is provided demonstrating how South African security & justice markets are not under state control.

As for William Morris, let me use your own words against you:

And he was WRONG. Socialism did not bring social equality, did not eliminate class structures and hierarchies, and has not removed the ability to have power over others when & where it has been tried. In fact, it is logically incapable of doing so, because it requires the collective to be more important than the individuals with it, and it requires collectives are given the means of having agency (the state). The same is true for communism at its core.

Groups naturally do not have agency, because there is no single mind governing the group. Only individuals have agency, and because of this the concept of socialism, indeed any form of collectivism, is inherently flawed from a logical perspective.

I have no problem people voluntarily working together, and expending their collective effort for a common goal, or voluntarily agreeing to live as part of a democracy. Those concepts are not unique to democracy or socialism, however, and in some cases within those systems of organisation, the "voluntary" bit is optional. From experience, it is rarely taken into consideration.

Voluntary actions are inherent in capitalism, however, and capitalism has never required a state in order to work.

As for Popper, though I admire his philosophy regarding science and the scientific method, he for some reason fails to apply the same reasoning here. His arguments on exploitation ignored Hume's guillotine. A government is and will always be unable to optimally regulate markets of any kind, because it cannot know all of the inherent needs and wants of the market and all the consumers within it. Its attempts at doing so inherently are examples of the administrator's fallacy, just as the concept of democracy itself is a glorified bandwagon fallacy through and through.

First, I'll start by saying that I define anarchism as “libertarian socialism.” That is, classical anarchism. Anarchy means “no rulers,” and anarchists have traditionally taken that to mean no kings, no bosses, no landlords, etc. The kind of rulers that arise from capitalistic property are still rulers. Communist anarchism proposed communal ownership with democratic management. (Cf. Kropotkin, Malatesta, Bookchin) Mutualism and collectivism had a more nuanced approach, still with some sort of public ownership and democracy. (Cf. Proudhon, Bakunin) Then there was individualist anarchism, which wished to abolish allodial and fee-simple property, as we have under capitalism, and replace it with usufructuary private property and totally free markets. (Cf. Benjamin Tucker, Thomas Hodgskin, Lysander Spooner) In all cases, anarchists criticized rulers across the board. They disliked political rulers (kings/politicians), disliked official rulers (cops/theocratic priests), disliked economic rulers (bosses/landlords). “Anarcho-capitalism” is a departure from classical anarchism. While it has anarchistic tendencies and influence, it is not entirely anarchist. I don't call an “anarcho-capitalist” an anarchist for the same reason that I don't call a kid throwing a brick an anarchist. Anarcho-capitalism says that it is okay for people to be ruled over by bosses, because they have voluntarily entered into that arrangement. They say it's okay for a landlord to make rules for his tenants, since the property they live on is his. Thus, anarcho-capitalists consider any sort of rulership deriving from legitimately acquired property as being justified. Regardless of whether or not it is true that property can justify rulership, it is the case that anarcho-capitalists support some types of rulers that classical anarchists rejected, so anarcho-capitalism is a departure from the anarchist position.

Furthermore, when I was an anarchist, I identified with the classical anarchist tradition, being influenced mostly by Proudhon, Bookchin, and Benjamin Tucker. I advocated a free market with either usufructuary or Georgist private property within a system of democratic confederalism. Plus, anarcho-capitalism didn't exist when Morris and Shaw wrote these critiques of anarchism. So, it made sense to exclude "anarcho-capitalism" from the discussion.

You said: ”How can a state police service (South Africa) be an example of decentralisation?”

I was actually referring to the decentralized and competitive private security forces in South Africa, which operate much like the system that anarcho-capitalists advocate. Check out Law and Disorder in Jahannesburg. Btw, there actually are some aspects of Rothbardian security theory that I agree with, which I have written about here.

You said: “And he was WRONG. Socialism did not bring social equality, did not eliminate class structures and hierarchies, and has not removed the ability to have power over others when & where it has been tried.”

Actually, democratic socialism in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, Finland, has done exactly that. And these places only ever went partially socialist, not fully socialist. Where “socialism” has not worked is in places like Russia, where socialism was NEVER tried. Lenin, following Marxist analysis, thought that socialism could only come about with the full development of capitalism; cut-throat competition would lead to monopolies, which would then naturally be taken over by municipalities like natural monopolies such as water and electric companies were. Since Russia had a pre-industrial agrarian society, rather than a competitive market, when the Bolsjeviks took power, Lenin believed that “State Capitalism” (Lenin’s own term, btw) would have to be employed rather than Socialism. Instead of worker-owned cooperatives, Lenin opted for government-owned industry—State Capitalism, not Socialism. He thought that eventually the State would “wither away” and socialism would naturally emerge. Either way, I am more of an advocate of distributism rather than socialism, so it’s a moot point.

Also, you mentioned “communism” as requiring a State. Actually, that's completely untrue. Communism is defined as a stateless and classless society. Such things do exist, but usually only in small tribal “primitive” communities. There's a great deal of sociological and anthropological literature on the topic. (Cf. David Graeber’s works on anarchy in Madagascar and James Scott's The Art of Not Being Governed) Also, the communist idea of “from each according to ability, to each according to need” is the bedrock of our society, what governs our relationships with families and friends. You don't tally up points when your kids get food from the pantry. This is what David Graeber refers to as the "communism of everyday life"; sociologists and anthropologists have been talking about this for a couple hundred years now.

You said: “capitalism has never required a state in order to work.”

Actually, the opposite is the case. All real stateless societies have been based on primitive communism or gift economies. Capitalism has only ever emerged where States have come into being. One government invaded another, looted, and took all the gold; they then minted the gold into coin, gave it to the soldiers as payment, then required the subjects, conquered people in general, to pay taxes in this government-issued coin. The necessity of acquiring the coin in order to pay taxes created a general demand for it, bringing markets into being. Barter, contrary to classical economics’ claim, never arose anywhere until after monetary systems had existed and collapsed. There is a great deal of archaeological and anthropological literature and research to back this up. (Cf. David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years)

You said: “A government is and will always be unable to optimally regulate markets of any kind, because it cannot know all of the inherent needs and wants of the market and all the consumers within it.”

I am familiar with the arguments against central planning. I actually agree with them, as does Karl Popper. That’s why both myself and Popper advocate markers for the distribution of goods rather than central planning. You should check out my post Markets Are Not Perfect, where I look at a few instances of market failure and how government intervention can rectify the problem. And, for the record, I am both pro-market and against central planning.

You should check out Markets Not Capitalism (book) for a look at a more classical market anarchist perspective, one that isn't exactly anti-Rothbardian btw. Also, maybe check out Benjamin Tucker's Individual Liberty, a classical market anarchist work. Tucker and Spooner heavily influenced Rothbard.

That is wonderful post sir. it is very interesting and great writing experience.

@ekklesiagora

Thanks sir...

Upvoted...Resteemed...

Cheers~~~

Beautifull post i like it

Shaw and Morris story is very interesting. Its really a worth ready post and I'magree with your point of rejected anarchism in favor of social democracy.

Again such a wonderful and interesting topic..

@ekklesiagora sir...

Actualy your blog is very interesting to me...uncommon knowledge...uncommon ideas...uncommon blog...

Nicely done sir...

I have rejected the notion of social democratic support.

I agree with you, because anarchism can harm people, and can make people not peaceful

Isn't the U.S. a republic by name and oligarchy in reality? I don't see how the elections say much about democracy as a concept. In fact, don't many anarchist thinkers support anarchism in the name of democracy, or at least pure democracy?