The Debate That Wasn’t: Political Correctness and Swinging at Phantoms

It’s interesting. When I make the attempt to examine how my own psyche works, one of the things I consistently find is how much works of art across various disciplines (painting, poetry, photography, fiction, comics, picture books, cinema, music) impact the way I see cultural and political issues.

Case in point. The other day, I was reflecting on the films of Richard Linklater. If you’re not a crate-digging film nut, you may be familiar with some of his more popular stuff like School of Rock, Dazed and Confused or the much celebrated Boyhood. I love those films but the ones I was pondering were his philosophical “idea” movies like Slacker, Waking Life and the Before Sunrise series. One of the things you see in these films, regardless of the story, is characters exploring ideas with one another, usually in conversation.

In all of these movies, Linklater does a remarkable job of signaling that, as human beings, there is little we know for certain and it may be possible that shitloads of things, even contradictory things, are true at the same time. What’s really interesting about these films is that, instead of leaving you with a sense of futility or despair at the absence of definitive truth, what you walk away with is a kind of delight in being able to play with and connect different ideas. And the other thing that fires my imagination about the films is that, as the audience, we’re invited to identify and care about people who are both heroic seekers and very small and ordinary at the same time. As tiny mortal beings full of incredible potential in a vast, mysterious universe that will eventually swallow us, that’s all of us too.

And why was I reflecting on all this? I had to think about that because I didn’t know. Then I realized it was because I was getting ready to watch the recently filmed debate about political correctness put on by the Munk Debates organization in Toronto. To get myself in the right headspace to remain open to the various points of view that would be articulated (and so I could credibly write about it), Linklater’s films were reminding me to hold ideas lightly (with humility) while still taking them seriously.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

So, what about political correctness?

I was at a small left-leaning liberal arts college during the first big wave of political correctness in the early 90s. It was a strange thing to be in the middle of because the dynamic had this way of cancelling itself out by simultaneously bringing up important issues and then shutting down discussion when participants unfamiliar with the norms of radical marginalized discourse tried to engage. I would sum the whole thing up as a hopeful bummer. A missed opportunity for people to understand one another.

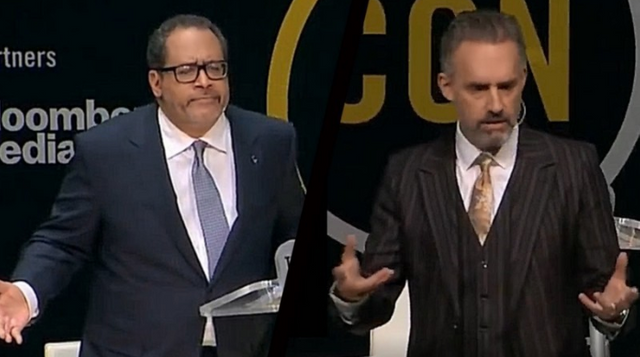

Given the missed opportunities, I thought this had the potential to be a really illuminating debate. On the side positing that political correctness represents progress were two Americans, professor Michael Eric Dyson of Georgetown and journalist Michelle Goldberg. On the side advocating that political correctness does not rep progress was the enormously popular (and, in some quarters, enormously reviled) Canadian psychologist and professor Jordan Peterson, along with British actor and activist Stephen Fry.

What was amazing was how quickly the whole thing fell apart and disintegrated into acrimony, personal attacks, name-calling and tangents. Again, a hopeful bummer. With so many issues influencing a new kind of political correctness that has been reaching beyond its usual residence on college campuses — the entry of the #MeToo movement into the workplace, an increased interest in socialism and anti-capitalist politics among the young, the continued struggle of black Americans to be treated justly and equally, immigrant rights in the face of imprisonment and deportation, fights over the tearing down of old statues, the newfound visibility of transgender people, struggles over what constitutes hate speech (and on and on) — you’d think the ground would have been exceptionally fertile for a fruitful debate on whether or not political correctness has been helping or hindering progress in the West. After all, many of these are life-or-death issues.

I noticed a couple of areas where the participants blew it from the outset:

No one provided a definition of what the fuck political correctness is, how it gets expressed or what its goal happens to be. Michelle Goldberg only went so far as to call it a slippery concept. Stephen Fry spent time lamenting that the debate was not covering the assigned topic (but did little to pull things back on track).

No one provided a viewpoint on what the group considered to be societal progress. This is kind of astonishing given that we’ve got countries like the U.S. and the U.K. seeing their middle classes get decimated, poverty, homelessness and addiction rise, demagogues gain power, climate change, pollution and disease continue to wreak havoc, etc. That shit ain’t progress, by any stretch of the imagination. But no discussion of that.

The debate was positioned as left versus right. This kind of setup might seem pro forma, but I actually saw it as a huge foundational problem that, more than anything, wrecked the positive potential of the debate.

It’s this left/right dichotomy that I’d like to dig into

It’s perfectly legitimate to organize a debate around a question with the construction of opposing sides. That’s a traditional way of putting together a debate and not very controversial. What was disheartening, though, was the way in which the two sides immediately started framing things as left vs. right and ascribing ideologies to one another. Not only did this obscure their ability to honestly debate the issue of political correctness, but it also meant that the opponents couldn’t see one another clearly.

A few examples:

If you take even a cursory look at Michael Eric Dyson’s work and public dialogue over the past several years it becomes very difficult to see him as a man of the left. Perhaps earlier in his career when he was closer to his mentor Cornell West, but as he began to spend more and more energy defending the neoliberal policies of Obama and then, in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election, Hilary Clinton, Dyson emerged as yet another academic courtier to power. What remains of the American left after the cultural and political fallout of the 60s and early 70s will tend to lean on a nonpartisan and systemic critique of power, as well as a focus on social movements. That’s simply not where Dyson’s head is at, despite his ability to articulate how the many manifestations of racism disfigure American life. He’s a Democrat. And today’s Democratic party fears and loathes the actual left.

Goldberg is a mainstream journalist writing for mainstream publications. There’s nothing in her background or work to suggest she’s part of the left in the U.S. She’s a partisan Democrat, a Russiagater and fairly anathema to systemic critiques of power. Guys like Chris Hedges or Glenn Ford would make mincemeat out of her and Dyson.

But Jordan Peterson, who I think offered one of the better structuring ideas of the debate by highlighting the tension between group and individual identity as endemic to political correctness, couldn’t resist casting Dyson and Goldberg as part of THE LEFT. Then, instead of assailing the notion that political correctness (undefined as it remained) is helping society progress, he went after them as his conception of the THE LEFT. Swinging fists at phantoms.

This misperception led to somewhat off-topic arguments about critical theory, deconstructionism, tyranny and genocide.

Dyson and Goldberg did similar things to Peterson, casting him as a part of the retrograde right they felt obliged to attack. In doing so, they failed to actually see Jordan Peterson who, if you take a more dispassionate look at his work, is simply not classifiable as a right-wing ideologue (though many on the right have latched onto aspects of his analysis). As a result, they placed him in a role for which he didn’t audition, as an ignorant, privileged, racist, sexist white man. While some of this may be true about Peterson—and he has, with his characteristic passion and sincerity, said some silly things about men and women in the workplace (which, given his long time in academia, he knows little about) and many other issues as well—his core ideas are multidisciplinary and not immediately political. He’s a self-avowed non-ideological Jungian who is genuinely terrified at the prospect of societal collapse and global nuclear war. Additionally, his intense and broad study of Christianity should have greatly interested the minister Dyson, but no dice.

And Fry? Well Fry they essentially ignored. And, despite that, he asked one of the most pertinent questions of the debate: that being, whether or not political correctness, as a method for societal change, has been effective.

This is not an idle question. Particularly in the U.S., we’ve got a society that’s increasingly polarized and, not unlike the 60s, in danger of tearing itself apart. Even if you hold the view that a huge portion of the society has deep-seated attitudes that make a decent, just and sustainable world impossible (which I do), the question remains: How do you change that?

One of the ideas they had in the 60s was to stand in front of Army induction centers and scream at the poor fucks we were being sent off to die in Vietnam. This certainly wasn’t the antiwar movement’s shining moment of tactical brilliance in change-making (thankfully, they had other brighter moments). All it did was piss off working class people and make them dig deeper into the views they already had. So what about the tactics of Twitter swarming, shaming, shouting, labeling and the like? The effectiveness of these methods for producing societal change is genuinely worth debating. But that debate never happened. And another great opportunity zoomed on by.

Did the debaters hold their ideas lightly and with humility? Well, perhaps that was too much to ask from a debate predicated on winners and losers (Peterson and Fry won, incidentally).

But, from a tactical perspective, let me leave you with this imagined scenario:

A far right commentator is invited to speak at a large university. Most students don’t support this person’s views, in fact are virulently opposed to them. Many campus groups meet in advance of the speech. What should we do? Mass rallies? Coordinated shout-downs? Block the airport? Groups meet for days about it. Finally, the big night arrives. Campus officials are shitting their pants at the potential conflict. As the far right person takes the stage, hundreds of students file silently into the lecture hall. Each wears a simple white tee shirt with one word scrawled on the front: LOVE. The person delivers their speech. The students in the tee shirts, who far outnumber the students without them, listen in complete and utter silence. No yelling. No heckling. No clapping. When the speech is over, each student rises and files silently out of the lecture hall. A note is handed up to the speaker. They open it. It says: “Come dance with us tonight.”

Perplexed, the speaker leaves the lecture hall through a back door. When they get outside they find a massive gathering of people. There’s a drum circle, saxophones, singers. Everyone’s dancing and beckoning the speaker into the party. There are young men and women from all walks of life. The speaker joins them. They dance all night. Eventually, campus security has to shut the party down because it’s unauthorized.

The speaker remembers this night for the rest of their life and, ever since, finds it a little more difficult to hate people. Just a little.

Check out the debate and see what you think:

As always, thanks for reading.