What Does the Electoral College Have to Do with the Hunger Games?

There has been a lot of discussion and division over the Electoral College in recent years, especially after the 2016 US presidential election when Hillary Clinton won the popular vote but lost the election (as decided by the Electoral College).

Let’s be clear: regardless of which way you lean politically or where you live, a lot was on the line with the 2016 election. So it’s no surprise that the outcome spawned a heated discussion about the Electoral College.

But there was (and is) a problem with most of this discussion: it’s intellectually very shallow. By that I mean that many involved in the discussion have only a trivial depth of knowledge on the topic, fed mostly by headlines and tweets. This is a problem on both sides of the spectrum and can be summed up on a Post-It: “Democracy!” vs “Constitution!”.

Do Something Out of the Ordinary: An Intellectual Deep-Dive

To really understand the Electoral College (and more importantly to understand your position on it) we need to do something out of the ordinary: we need to dig deeper. We need to get past the headlines and the tweets and whether or not our candidate won in a recent election and really understand the how’s and why’s of the Electoral College.

Almost everything about our modern society (headlines, social media, clickbait, video games, shopping, etc) points towards instant-gratification and sets us up to be predisposed against doing intellectual deep-dives. There have been lengthy studies on how this is actually rewiring our brains. We generally have just enough information to convince ourselves we’re experts on a given subject and to give ourselves license to jump into a discussion on the topic with vigor. That vigor usually lasts as long as it takes for someone with depth on the subject to bring up a point we’ve never heard of, let alone really considered, and then we revert to our cognitive bias and mentally move-on (or just keep restating our given position sourced from a recent headline).

But that pattern only leads to severe division and rests on a very shallow (and often false) foundation. Historically very little good has come out of that pattern. Quite the opposite, actually. Think “Hatfields and McCoys” on a national or global scale.

This kind of division and shallow conformity is really bad for a society. To borrow a tired phrase: it isn’t sustainable. You can see that in America now, everywhere you look. It’s affecting us right down to our Thanksgiving dinners with (or as a result without) our family and friends.

The solution is an intellectual deep dive. This has to be done on a personal level, and it has to be intrinsically motivated. CNN and Fox News can’t (and won’t) do it for you. Neither will the D’s or the R’s. Or the I’s. You have to want to do it yourself, and you have to actually take the time to do it yourself.

So, if you want to start your intellectual deep dive, keep reading.

The Metaphor of Panem in the Hunger Games

In the Hunger Games book series, written by Suzanne Collins, we have a (hopefully) fictional future where America has morphed over time into Panem, with 13 districts being subservient to the Capitol district where the money, politicians, and power reside. Each district has one or more specialty products or services they provide Panem, such as agriculture, fishing, power, weapons, luxury items, mining, textiles, lumber, etc.

In essence Panem has a deeply engrained class system.

The elite class in the Capitol largely lives off what is created in the districts. They have peace, prosperity, food, entertainment, healthcare and money that is out of reach for everyone in the districts.

The lower class, in complete contrast to those living in the Capitol, work long hours in dangerous jobs to barely eek out a living. Within the districts you have classes above the lower class with varying amounts of power, but very few people are in these classes. The vast majority are living in poverty. Even those at the top in the districts have a lifestyle far below those in the Capitol.

Suzanne Collins did an amazing job of painting a very clear picture of what it was like for the two classes, and the constant struggle between the two (a struggle the lower class was very, very aware of because it raged within them every time they saw the injustices in their daily grind).

So what does this have to do with the Electoral College?

When the Electoral College was created the delegates involved did an enormous deep-dive on not only the issues of the day, but on human nature in general, on the forms of government throughout history and how they worked out, and on the principles that governed them. Their daily debates were often heated and very in-depth. When they were done for the day they would continue the deep-dive personally, and in discussions with their constituents. Their knowledge was based on the collective lessons of history from a wide variety of supremely credible sources.

One of the major tug-of-wars was between the small states and the large states. The small states, with smaller and more rural populations, were concerned that with a straight popular vote their voices would never be heard, entirely drowned out by a handful of large states or even cities. It would only take a handful of large states to pool together behind a given candidate and that candidate would win, with the small states consistently losing to the superior numbers of the collective large states.

The delegates from the small states were very concerned about a popular vote. Charles Pinckney, delegate of South Carolina worried:

“The most populous States by combining in favor of the same individual will be able to carry their points.”

Gunning Bedford of Delaware put it most bluntly (speaking to the delegates from the large states):

“I do not, gentlemen, trust you. If you possess the power, the abuse of it could not be checked; and what then would prevent you from exercising it to our destruction? You gravely allege that there is no danger of combination.... This, I repeat, is language calculated only to amuse us. Yes, sir, the larger States will be rivals, but not against each other—they will be rivals against the rest of the States.”

But was their concern warranted? If the “will of the people” is honored, does it actually matter if the large cities and states always win? Every election has a winner and losers. By definition there will always be a minority. That’s how “democracy” works, isn’t it?

Applying the Hunger Games Metaphor to America

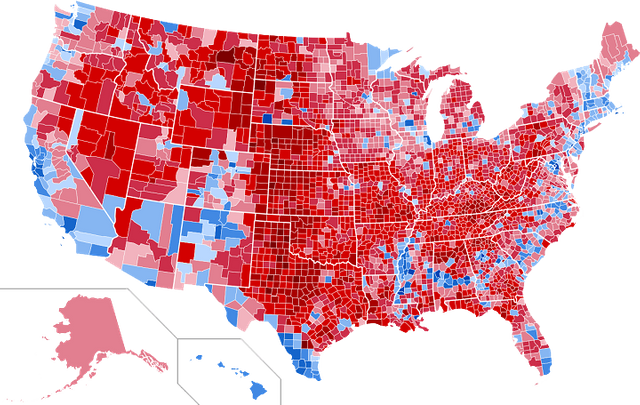

Let’s look at the 2016 election through the lens of the Hunger Games. Hillary Clinton won the popular vote with 65.8 million votes to Donald Trumps 62.9 million votes. We clearly have a winner. But over 20% of Clintons votes came from just 2 states: California and New York. If you ignore those two states (which I’m not suggesting) the tables turn and Donald Trump would win the popular vote by over 3 million votes.

Its easy to see how this happens. The population density in cities like New York or Los Angeles is way higher than in rural America. New York City has 28,211 people per square mile, compared to only 2,975 in Iowa City, Iowa (the most densely populated place in Iowa).

If America switches to a popular vote for the presidential election the elections will be decided by those living in cities more and more frequently until eventually (and maybe immediately) all US Presidents will be chosen exclusively by those living in big cities. Why? Because politicians want to win elections so they go where the votes are. Under a popular vote a state like Iowa may never see a presidential candidate again. Advertising dollars, volunteer efforts, visits, meetings, events, would all be focused on major population centers.

But would that necessarily be a bad thing?

I guess how you feel about that outcome depends on your personal view on the benefits of political power verses the downsides of a class system. It also depends on whether your focus is short term or long term.

Looking through the lens of The Hunger Games again, you can see how this would be a problem. New York City has 8.6 million people in it. You have to combine the entire states of Iowa, Montana, Delaware, North Dakota, South Dakota, Alaska, Vermont, and Wyoming just to equal the population of New York City. Generally speaking, those in New York City are likely to have fairly similar views politically and socially compared to the variety in the 8 states with the same combined voting power. Those in New York are unlikely to understand or appreciate the challenges of growing corn in Iowa, or mining and cattle ranching in Montana and Wyoming, or oil drilling in the Dakota’s, or issues facing a spread-out state like Alaska. New Yorkers may eat meat and own leather products, but cattle ranching is far from their minds. They may use transportation powered by oil, or use products made out of steel or copper, or eat corn or potatoes or a wide variety of other resources, products and foods produced in small states, but they aren’t necessarily concerned with the issues of those small states.

Having the president of a very diverse country be chosen consistently by a fairly homogeneous group, at the exclusion of entire segments of that country, is almost certainly a recipe for disaster. It may not end up resembling The Hunger Games, but history shows us it won’t work out well for the commoner. And ultimately the reality could end up even worse than the fiction portrayed in The Hunger Games.

Personally, I think the Electoral College is an elegant solution to a serious problem. It’s creation showed great foresight based on a solid intellectual and historical foundation that very few possess today. We’re far better off with it than without it.

This discussion, and the need for a wide-scale deep-dive and education campaign, are becoming critical: the "National Popular Vote" compact now has 172 electors on-board to subvert the Electoral College via a Constitutional end-run. If they hit 270 its game over for the Electoral College. They're doing this at the state level (which is something I agree with in principle, but this particular application of it is very dangerous), with Connecticut being the most recent state to pass legislation supporting it. This is ironic considering that "The Constitution State" was one of the small states that fought for their voice at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Roger Sherman was the oldest delegate there, and one of the most vocal, and was responsible for giving us the balance between the federal government and the states, known as the Connecticut Compromise. Unfortunately the elegant genius of his solution was largely gutted by the 17th Amendment and is largely responsible for giving lobbyists so much influence in our government.

Hopefully this has served as an effective appetizer and made you want to dig deeper. If so, enjoy your deep-dive! I’d love to know your thoughts on the pro’s and con’s of the Electoral College.