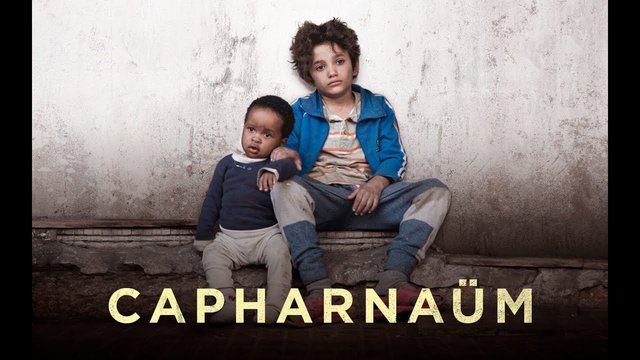

CAPHARNAÜM OR HOW TO TOLERATE THE MISERY - MOVIE REVIEW TV - (WARNING : Spoilers)

Capharnaüm or Capernaum was a town in ancient Galilee in which, according to biblical accounts, Jesus worked some of the miracles and recruited who his apostles would be. However, in the Nadine Labaki movie that bears this name, although it is located in contemporary Lebanon, there are no saviors or apostles or miracles ... or perhaps some of the latter a little pulled from the hair. The film, in this case, refers to the French term that indicates chaos or mess. Some of that is also from the perspective of the director, although it could be said that what is seen as chaos is part of an order or logic inherent in the current system.

The film, which won the Jury Prize in Cannes in 2018 and was nominated for an Oscar as best foreign film, begins with a child waiting in the prison for a doctor to check to see how old he is. The professional indicates that, when not seeing any milk tooth, surely he is about 12 years old. This first scene says almost everything: the boy has no identity document or knows his own age. He is a child but everything is in prison and in a situation of abandonment.

Zain (Zain al Rafeea), this child protagonist, decides, from prison, to bring his parents before a judge to accuse them of having brought him into the world, for making him suffer and to ask them not to have any more children. From that moment, the story will make a racconto of the last months or year of the child's life, showing the course through which he has passed until he reaches the place where he is today.

The life of Zain and his family takes place in an apartment too small for the number of children who live there with their parents Souad (Kawsar al Haddad) and Selim (Fadi Yousef), who already have one of their children imprisoned and support the family economy based on passing drugs through an unorthodox but ingenious method in jail and working Zain, the oldest of the most chic, in a market or kiosk in the neighborhood, which is run by a rather unpleasant character that only wants to conquer the 11-year-old sister, Sahar (Haita Izzam).

The child loads gas bottles, loads and unloads trucks, while looking forward to the school bus that passes by without anyone wondering why a child does not go to school. Not only does he take charge of supporting the work so that his family eats, but he also has the sagacity to discover that Sahar's first menstruation will enable his parents to force him to marry to get a mouth out of the house rather than feed; So he will do everything to hide the bleeding.

Labaki shows us a really beautiful and attractive boy by the established standards: with clear signs of abandonment and malnutrition but with eyes framed with camel eyelashes and a ease to handle life that resemble a little man. With supreme intelligence and sensitivity outside this world and oblivious to the pragmatism of the rest of the family.

Despite having stated in numerous interviews that this was a fiction based on reality and that, during filming, they wanted to have the least possible intervention, the director's perspective is too noticeable in this type of elements and in much of the story .

There is no doubt that Zain and the rest of those who star in the story are not professionals and that, despite this, the scenes are organic and feel "natural." However, it becomes difficult to sustain that affirmation of a fiction based on reality.

As if Zain's life was no longer miserable, due to certain circumstances that are not worth revealing, he goes on to share his life (and needs) with an illegal Ethiopian immigrant and his one-year-old son, who, like Zain He has not been registered since, due to his mother's illegality, he should not even exist.

After a while, Zain and the baby end up wandering around the worst places in Beirut in practically inhuman conditions, without some kind of help from at least one adult without second intentions or any institution, whether state or non-governmental. Something ... a hint of humanism. No. Any possible solution is not even presented so that at least it is denied. Directly does not arise. These people are ignored by the environment, and are abandoned to their own fate and strategies to survive. But beware! The state becomes very present when Zain commits a crime and must be punished. There the whole apparatus unfolds: not only the state one, but also that of the adult world that moves through the mass media and gives rise to the little boy who, until then, had been invisible, asks his parents for justice.

During the little more than 2 hours of the movie, I couldn't stop thinking about the horror I was watching; However, I couldn't stop seeing her. There, sitting in my armchair, it represented exactly the result of that kind of cinema that does not finish closing me. The one that generates fright but is so "friendly" that prevents us from running our eyes or covering our eyes. A bearable fright. A worrying result if we stop to think about it for a minute.

This reality should be horrifying but it is shown in such a way that we end up consuming it even knowing that we cannot do anything to change it. And it is bearable because there are children with beautiful faces and tender looks, because there are almost comic scenes (like that Zain manages to watch TV from a very remote house) or because the horror happens with a background music that makes us can stand it a little more.

That aesthetic misery is what does not close me of this type of movies. I would prefer something more heartbreaking that forces me to take care of what I leave. Of course, Capharnaüm is not a documentary, but a fictional story. However, it is Labaki herself who says it is based on reality and who claims that they tried to intervene as little as possible ...

That statement leads me to think of another type of “non-interventions” that are present (or absent) in this story: the system. The damn system that makes there exist inhuman and other privileged lives that enjoy such privileges at the expense of the exploitation of others.

Zain accuses his parents of their suffering and asks them not to have children again because they will suffer the same fate as theirs, because they will suffer just as he does. But can they be blamed for the life they lead and give to their children? Are they responsible for being the "scum" or the discarding of society or are they not victims and sufferers too?

A look too biased about the injustice of the world, in my opinion.

Labaki does not show the failures of the system to explain the suffering of these children of misery. It is almost as if this poverty exists "because yes" or worse still: because the parents did not do enough to get out of it or did not stop having children to prevent them from suffering.

I read or heard a film critic say that at this moment I cannot remember that one of the mistakes of The man next door (Cohn, Duprat 2009) is never to show the look from the house of the character of the popular sector, played by Daniel Araoz. Throughout the film, the point of view of the neighbor ricachón and snob is shown. That speaks of the position of its creators. They are telling us something about their position.

Something similar happens with the director of Capharnaüm when deciding to show only the misery among the poor and not the inequality as its cause. Inequality can only be seen in contrast to those who have much (and the ways in which they have it) and those who have nothing. There is no other way to show it since it is a relational concept, and showing only one part only deepens that injustice, with all that that entails.