Anarchism As Part of the Republican Tradition

The United States was originally founded on republican principles, but shortly after the American Revolution there was an intellectual shift away from republicanism and towards liberalism. The republican tradition defines liberty as non-domination, whereas the liberal tradition defines liberty as non-interference. According to the republican tradition, democratic self-determination is essential to freedom; for people must not be dominated by others. According to the liberal tradition, free trade is essential to freedom; for people must not be interfered with. Republicanism sees democracy as a core component of a free society, but liberalism does not care about the particular form of government as much as it cares about what the government does. As far as the liberal tradition is concerned, a monarchy is just as good as any other form of government, so long as the monarch does not interfere in the lives of individuals. For more information, see my post on The Genealogy of Liberty.

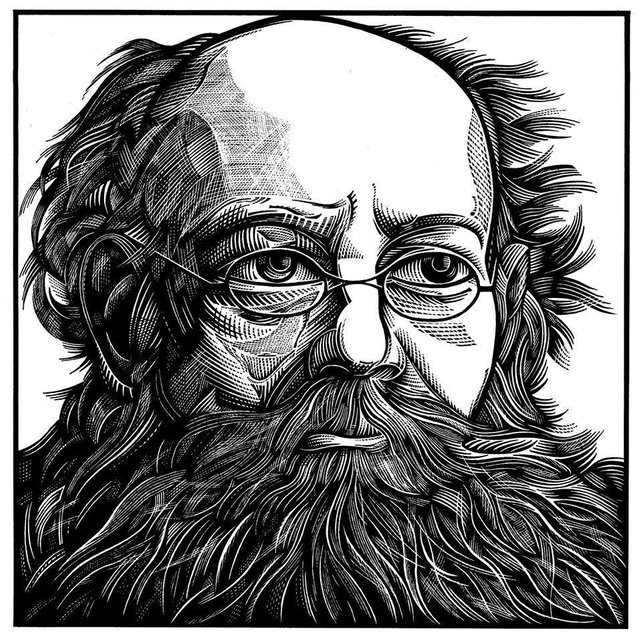

The OG anarchists—Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin, and Peter Kropotkin—were all technically within the republican tradition. They defined freedom as non-domination, sought to eliminate the domination of man over man, and advocated a form of representative democracy (delegative democracy) alongside a form of federalism (confederalism). Classical anarchism, as espoused by these thinkers, was the most radical form of republicanism. The anarchists advocated more direct or participatory democracy at the local level, with representation through delegates for politics at a larger scale. The modern expression of this classical anarchist tradition would be the "democratic confederalism" of Murray Bookchin and Abdullah Öcalan. This republican tradition of anarchism is the dominant tradition amongst anarchists in Europe.

Yet, in the early days of anarchism, America had already moved away from the republican tradition and embraced liberalism. The republican tradition, like the OG European anarchist tradition, saw freedom as non-domination and, therefore, saw democracy as a means of achieving liberty. The liberal tradition, on the other hand, saw freedom as non-interference and, therefore, saw "free trade" or capitalism as necessary. The early American anarchists very quickly repackaged anarchism by replacing the civic republican ideas with liberal ideas. Josiah Warren's individualism reigned supreme, with its anti-democratic sentiment. Benjamin Tucker took the individualism and liberalism of Warren and refashioned anarchism along liberal lines. His "individualist anarchism" was distinctly American and distinctly non-republican. Rather than establishing direct democracy as an alternative to the State, as European anarchists proposed, Tucker proposed privatizing the State, or allowing for companies in the private sector to compete with the government and offer their own governmental services. Individualist anarchism ultimately developed into "anarcho-capitalism" as espoused by Murray Rothbard and David Friedman. This is the polar opposite of classical anarchism as espoused by Proudhon and Kropotkin.

When I was an anarchist, I identified with the republican tradition of anarchism. I have since stopped identifying as an anarchist and now identify as a civic republican (basically a social democrat). This transition from anarchism to republicanism was no big shift in thinking for me. As an anarchist, I was already a civic republican. I held then, as I hold now, that freedom as non-domination is of utmost importance. However, I now believe that certain more centralized forms of administration and power may be necessary for guaranteeing this freedom. I see land value tax and universal basic income, alongside single-payer healthcare, as being far more libertarian than decentralized "free" communes without such measures. While I am highly dissatisfied with most existing States, I believe that some sort of State will be necessary in order to allow for a free society to exist.