Life of a Doctor in Venezuela

Insecurity within the hospital

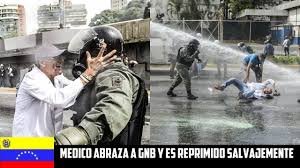

Because in addition to the salary, the doctors have also protested throughout the country because of the insecurity.

In the University of Caracas, which is between the two or three most important hospitals in the country, there were two shootings in the last year in the emergency area.

The cars of several doctors have been robbed or robbed in the parking lot in front of the hospital, according to the staff.

And on the seventh floor of the building, which is an area out of service since the hospital was built, doctors believe there is a band dedicated to theft, so they recommend not going down or up the stairs.

To that the doctors add a problem of politicization.

"If we complain, they say it's because we are from the opposition," Gerson Casanova, who is president of the Society of Resident Physicians of the Hospital, tells BBC World.

"But that's just an excuse to not recognize that the hospital is wrong," he says.

"With your hands tied"

But while insecurity, low wages and politicization complicate the work of these Venezuelan doctors, they say that nothing hurts their daily lives more than the shortage of medicines and supplies.

When BBC World was in the University, there were no solutions or material for sutures or blood reserves for transfusions.

Even the cap they gave us to enter the operating room - where we saw a room full of equipment out of service in a covert way - was actually a shoe lining.

Doctors should carry their own computers if they do not want to write a medical history at hand and, if they do not have cell phones, they could not communicate with their colleagues in the other floors or take pictures of the X-rays, because there is no paper or printers.

"We are with our hands tied", says, frustrated, Dr. Joseph Sáez, who works in the area of surgeries.

"We are unable to do good to patients," he complains, to give the example of patients with diabetes, that there are no physiological solutions are treated with glucose solutions and insulin, a maneuver that stops a crisis but has serious consequences long-term vision, tension and heart, among others.

"They did not have to pass away"

Dr. Ortiz tells us that she has come to sit and cry because of the impotence of not being able to heal patients who, she says, "did not have to pass away."

And remember the time he spent 18 hours looking for supplies and antibiotics throughout the hospital to a patient who had an infection, until he died.

It also evokes the day when, in the absence of mechanical ventilators, a patient with a respiratory arrest had to be ventilated manually for 24 hours by several doctors until their hands became chambered and the patient died.

The doctors of the University have received talks from psychiatrists to face the emotional impact that the current situation implies.

"Many of us have entered a state of depression," says Ortiz.

"We do not want to go to the hospital because a patient is going to arrive and I'm not going to have anything to take care of."

"People are dying in your face and you should go and tell the family that their relative died because there was no way to treat them," he laments.

And he concludes: "It's a feeling of helplessness"