OPEC production cut papers over cracks in US-Gulf relation but for how long?

By James M. Dorsey

A podcast version of this story is available on Soundcloud, Itunes, Spotify, Stitcher, TuneIn, Spreaker, Pocket Casts, Tumblr, Podbean, Audecibel, Patreon and Castbox.

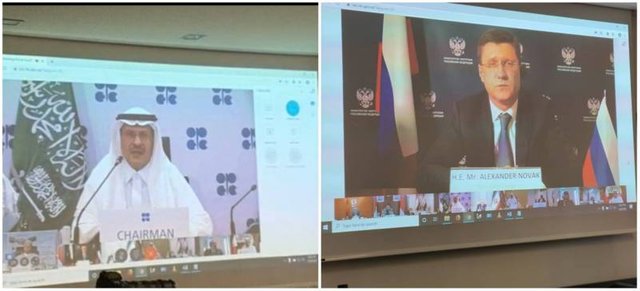

A decision by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and non-OPEC producers like Russia to temporarily end a price war and cut production amounts to a time-out rather than an end to what is likely to erupt at some point in the future as a tripartite war.

More immediately, the decision averts a significant deterioration in relations between the United States and Saudi Arabia and in the kingdom’s wake, the United Arab Emirates.

Nearly 50 Republican US lawmakers warned Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on the eve of this week’s OPEC oil ministers’ videoconference that economic and military cooperation between the United States and Saudi Arabia was at risk.

The congressmen demanded that the kingdom end a price war with Russia that collapsed oil prices as the world struggled with the coronavirus pandemic and its devastating human and economic fallout.

The UAE had joined Saudi Arabia in raising production in a move that was sparked by Russia’s initial refusal to extend production cuts agreed early this year but more fundamentally was designed to knock out competition from US shale producers that had turned the United States into the world’s largest producer.

In a twist of irony, Saudi Arabia, Russia and the UAE, the initial warring parties, share a desire to take out the US shale industry in an environment in which the value of their reserves is likely to diminish in the next decades as a result of shale and renewables. Add to that a Russian interest to undermine US power where it can.

The stakes for the key warring parties, particularly the Gulf states and the US, couldn’t have been higher but were raised by the collapse of the oil price as well as demand in the midst of a global economic meltdown.

For Saudi Arabia and the UAE, the stakes were their relationship with the US and significant reputational damage with a move that put at risk tens of millions of American jobs at a time at which 17 million people joined the unemployed in the United States in the past four weeks.

Oil is but the tip of an iceberg in efforts, particularly in the case of UAE, to manage a divergence in interests with the United States without tarnishing the country’s carefully groomed image as one of Washington’s closest allies in the Middle East.

Differences first emerged with Emirati gestures designed to ensure that the country would not be a target in any military confrontation between the United States and Iran.

The UAE began reaching out to Iran a year ago when it sent a coast guard delegation to Tehran to discuss maritime security in the wake of alleged Iranian attacks on oil tankers off the coast of the Emirates.

The Trump administration remained silent when the UAE last October released US$700 million in frozen Iranian assets that ran counter to US efforts to strangle Iran economically with harsh sanctions.

While the United States reportedly blocked an Iranian request for US5 billion from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to fight the virus, the UAE was among the first nations to facilitate aid shipments to the Islamic republic.

The shipments led to a rare March 15 phone call between UAE foreign minister Abdullah bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan and his Iranian counterpart, Mohammad Javid Zarif.

UAE officials stressed, however, that there would be no real breakthrough in Emirati-Iranian relations as long as Iran supported proxies like Hezbollah in Lebanon, pro-Iranian militias in Iraq and Houth rebels in Yemen.

The UAE gesture contrasted starkly with a Saudi refusal to capitalize on the pandemic.

Instead, Saudi Arabia appeared to reinforce battle lines by accusing Iran of “direct responsibility” for the spread of the virus. Government-controlled media charged that Iran’s allies, Qatar and Turkey, had deliberately mismanaged the crisis.

Moreover, the kingdom, backing a US refusal to ease sanctions, prevented the Non-Aligned Movement from condemning the Trump administration’s hard line.

In a further indication of a divergence of interests, the UAE, according to Middle East Eye, has been trying to sabotage US support for Turkey’s military intervention in northern Syria as well as a Turkish-Russian engineered ceasefire in the region.

In other words, the UAE was at odds with Russia, not just with regard to oil, but also Russian efforts to prevent the situation in northern Syria from spiralling out of control and further jeopardizing Moscow’s alliance with Turkey.

Middle East Eye reported that UAE Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed had promised Syrian President Bashar al-Assad US$3 billion, $250 million of which was paid upfront, to break the ceasefire in Idlib, one of the last rebel strongholds in Syria.

On opposite ends of the Middle East divide, Prince Mohammed had hoped to tie Turkey up in fighting in Syria, which would complicate Turkish military support for the internationally recognized Libyan government in Tripoli. The UAE aids rebel forces led by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar.

The outlet said that a tweet by Prince Mohammed on March 28 declaring support for Syria in the fight against the coronavirus was designed to keep secret the real reason for the UAE payment.

“I discussed with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad by phone the repercussions of the spread of the coronavirus and assured him of the UAE’s support of and assistance for the brotherly Syrian people in these exceptional circumstances. Human solidarity in times of adversity supersedes all else, Sisterly Syria will not be alone in these difficult circumstances,” Prince Mohammed said.

Its unlikely that Prince Mohammed’s explanations will convince policymakers in Washington.

Nevertheless, the United States, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are likely to paper over cracks in their relations in the short term facilitated by a pandemic and economic crisis that leaves no one untouched. It probably is, however, only a matter of time for them to re-appear.

Dr. James M. Dorsey is an award-winning journalist and a senior fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore. He is also an adjunct senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute and co-director of the University of Wuerzburg’s Institute of Fan Culture in Germany.