Scientists are seeking new strategies to fight mutiple sclerosis!

James Davis used to be an avid outdoorsman. He surfed, hiked, skateboarded and rock climbed. Today, the 48-year-old from Albuquerque barely gets out of bed. He has the most severe form of multiple sclerosis, known as primary progressive MS, a worsening disease that destroys the central nervous system. Diagnosed in May 2011, Davis relied on a wheelchair within six months. He can no longer get up to go to the bathroom or grab a snack from the fridge.

Davis hoped life might improve when he was chosen in 2012 to participate in a clinical trial of a drug called ocrelizumab. The drug offered a first sliver of hope for patients waiting for a cure, or at least something to slow down the disease’s staggering march. Early research suggested the drug could help some of the roughly 60,000 people in the United States, like Davis, suffering from primary progressive MS. The drug also held promise for patients with the other major form of the disease, relapsing-remitting MS, which afflicts about 340,000 people nationwide.

For some people, ocrelizumab seemed to work. Brain scans of patients with primary progressive MS showed fewer signs of damage and the patients’ ability to walk deteriorated more slowly than in individuals who received a placebo, researchers reported in January in the New England Journal of Medicine. The drug also helped people with relapsing-remitting MS, which, as the name implies, includes shifts between disability and wellness. Over a year’s time, these patients experienced about half as many flare-ups as those taking another commonly prescribed drug, a different research group reported in the same issue of the journal.

Ocrelizumab was heralded as a breakthrough, and in March, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved it as a treatment for primary progressive and relapsing-remitting MS. Genentech now sells the drug as Ocrevus.

“We finally have an approved therapy for primary progressive MS,” says Fred Lublin, a neurologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. The first drug to treat relapsing-remitting MS came on the market in 1993, Lublin notes. Now, nearly a quarter century later, there’s something that helps some people with the most aggressive form of the disease.

With that hopeful note, though, comes frustration. Ocrevus isn’t a cure, and it offers no relief for 30 to 40 percent of patients with primary progressive MS. Davis was in that disappointed group.

In fact, none of the 15 FDA-approved drugs for MS, which all modify or suppress the immune system, actually stop the disease. The drugs only reduce the number and severity of flare-ups and, in some cases, slow the visible marks of brain damage.

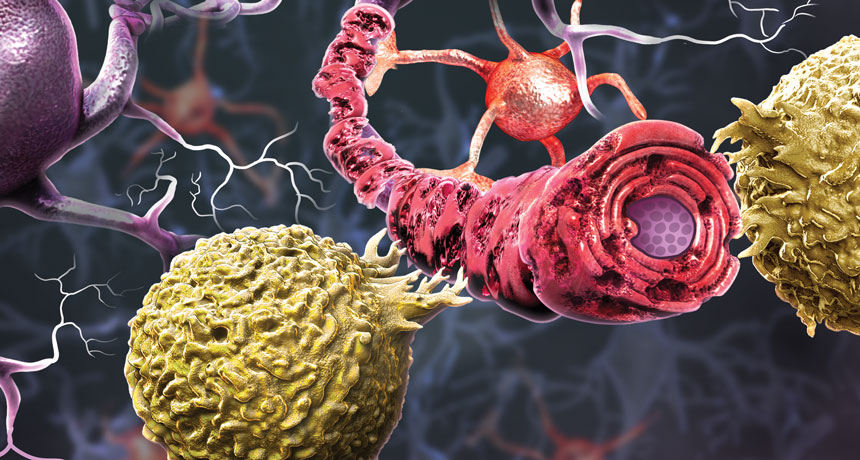

“Multiple sclerosis is arguably the most complex disease ever described,” says Sergio Baranzini, a geneticist at the University of California, San Francisco. The disease is so complicated, he says, because it involves two of the body’s more complex systems — the nervous and immune systems. Scientists don’t yet have a good handle on where the damage begins. Does a problem in the nervous system spur an immune response that leads to additional damage to the brain and spinal cord? Or does the immune system attack first, dispatching disease-fighting cells into the brain, where they batter and kill nerve cells? What causes the initial nerve damage or incites the immune attack is still a big question. Scientists aren’t even clear whether multiple sclerosis is a single disease or a multitude of maladies.

With so many unanswered questions, researchers have begun looking for potential treatment strategies outside the immune system. Targeting problems in the nervous system, together with the harmful immune reactions, is essential, scientists say. Some researchers have begun scrutinizing the malfunction of specific organelles within nerve cells, or neurons. Others are analyzing the gut’s community of microorganisms, its microbiome, which is considered a bridge between the environment and the body. Those researchers are following up on observations that environmental influences play a role in MS. The research is in early stages. But for a challenging disease like MS, attacks on multiple fronts may be exactly what it takes to help Davis and others who are running out of time.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/scientists-are-seeking-new-strategies-fight-mutiple-sclerosis