Tracking the birth of a 'Super-Earth'

'Synthetic observations' simulating nascent planetary systems could help explain a puzzle -- how planets form -- that has vexed astronomers for a long time.

A new model giving rise to young planetary systems offers a fresh solution to a puzzle that has vexed astronomers ever since new detection technologies and planet-hunting missions such as NASA's Kepler space telescope have revealed thousands of planets orbiting other stars: While the majority of these exoplanets fall into a category called super-Earths -- bodies with a mass somewhere between Earth and Neptune -- most of the features observed in nascent planetary systems were thought to require much more massive planets, rivaling or dwarfing Jupiter, the gas giant in our solar system.

In other words, the observed features of many planetary systems in their early stages of formation did not seem to match the type of exoplanets that make up the bulk of the planetary population in our galaxy.

"We propose a scenario that was previously deemed impossible: how a super-Earth can carve out multiple gaps in disks," says Ruobing Dong, the Bart J. Bok postdoctoral fellow at the University of Arizona's Steward Observatory and lead author on the study, soon to be published in the Astrophysical Journal. "For the first time, we can reconcile the mysterious disk features we observe and the population of planets most commonly found in our galaxy."

How exactly planets form is still an open question with a number of outstanding problems, according to Dong.

"Kepler has found thousands of planets, but those are all very old, orbiting around stars a few billion years old, like our sun," he explains. "You could say we are looking at the senior citizens of our galaxy, but we don't know how they were born."

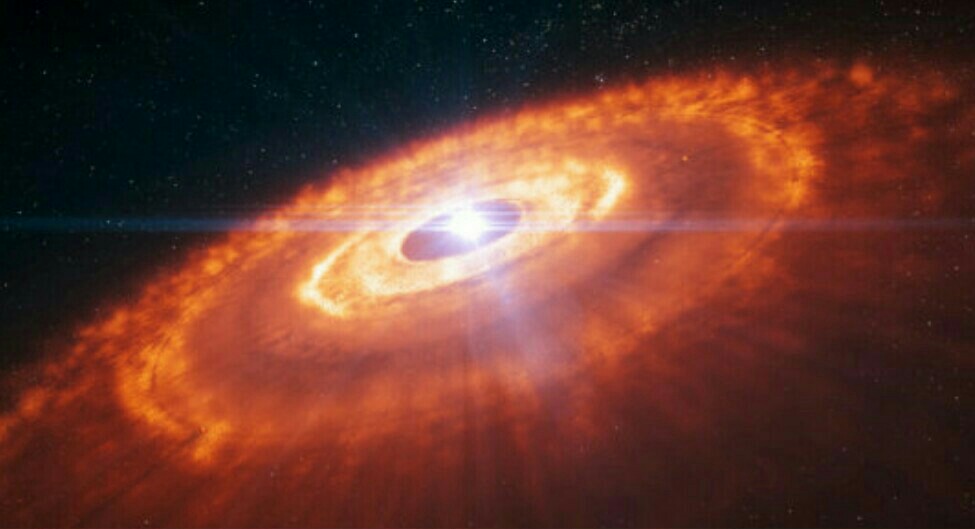

To find answers, astronomers turn to the places where new planets are currently forming: protoplanetary disks -- in a sense, baby sisters of our solar system.

Such disks form when a vast cloud of interstellar gas and dust condenses under the effect of gravity before collapsing into a swirling disk. At the center of the protoplanetary disk shines a young star, only a few million years old. As microscopic dust particles coalesce to sand grains, and sand grains stick together to form pebbles, and pebbles pile up to become asteroids and ultimately planets, a planetary system much like our solar system is born.

"These disks are very short-lived," Dong explains. "Over time the material dissipates, but we don't know exactly how that happens. What we do know is that we see disks around stars that are 1 million years old, but we don't see them around stars that are 10 million years old."

In the most likely scenario, much of the disk's material gets accreted onto the star, some is blown away by stellar radiation and the rest goes into forming planets.

Although protoplanetary disks have been observed in relative proximity to the Earth, it is still extremely difficult to make out any planets that may be forming within. Rather, researchers have relied on features such as gaps and rings to infer the presence of planets.

"Among the explanations for these rings and gaps, those involving planets certainly are the most exciting and drawing the most attention," says co-author Shengtai Li, a research scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico. "As the planet orbits around the star, the argument goes, it may clear a path along its orbit, resulting in the gap we see."

Except that reality is a bit more complicated, as evidenced by two of the most prominent observations of protoplanetary disks, which were made with ALMA, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile. ALMA is an assembly of radio antennas between 7 and 12 meters in diameter and numbering 66 of them once completed. The images of HL Tau and TW Hydra, obtained in 2014 and 2016, respectively, have revealed the finest details so far in any protoplanetary disk, and they show some features that are difficult, if not impossible, to explain with current models of planetary formation, Dong says.

[via ScienceDaily]

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/07/170711092823.htm