Reading Nikola Tesla – part 8: The coming age of aluminium

Here we are in 2018, over a hundred years later speculating about what could have been Nikola Tesla’s secret. I then think to myself: if only I could show you what I read, you would understand that there is no secret. When I read his articles and patents from 1900 onward, what I see is a man desperately trying to get his views across. He tries again and again in many different ways, but no-one seems to see what I see.

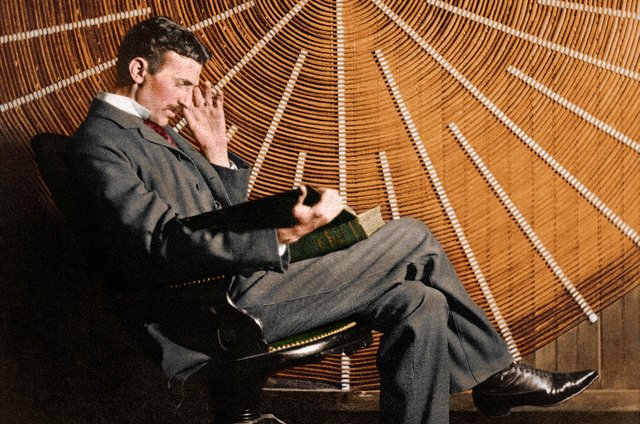

(Some internet fools say that Tesla is reading Boskovich here. As anyone can read in the article of May 20th, 1896 “Tesla’s Important advances”, he was reading one of the "Scientific Papers," of Maxwell)

It is my sincere wish that one day people will read Tesla’s articles and really understand what he is saying.

So… Let me take you by the hand an walk you through his most famous article: “The Problem of Increasing Human Energy”, published in Century Illustrated Magazine of June 1900.

In this eighth part we look at another metal; aluminium (or aluminum as some people say).

Previous parts can be found here:

Part 1: Laying a foundation

Part 2: What is electricity?

Part 3: Burning Nitrogen...

Part 4: How to overcome natural resistance

Part 5: Telautomatics

Part 6: Introduction to Harnessing the Sun’s Energy

Part 7: The Manufacture of Iron? Or ...

Slowly but surely Tesla presents us the working principles of his Magnifying Transmitter.

We continue in the main article where we’d left off.

THE COMING AGE OF ALUMINIUM

—DOOM OF THE COPPER INDUSTRY—THE GREAT CIVILIZING POTENCY OF THE NEW METAL.

What do Iron, Copper and Aluminium stand for? We know from the previous section that Iron stands for electric currents, we will see that all these metals do. They are currents with different characteristics.

With the advances made in iron of late years we have arrived virtually at the limits of improvement. We cannot hope to increase very materially its tensile strength, elasticity, hardness, or malleability, nor can we expect to make it much better as regards its magnetic qualities. More recently a notable gain was secured by the mixture of a small percentage of nickel with the iron, but there is not much room for further advance in this direction. New discoveries may be expected, but they cannot greatly add to the valuable properties of the metal, though they may considerably reduce the cost of manufacture. The immediate future of iron is assured by its cheapness and its unrivalled mechanical and magnetic qualities. These are such that no other product can compete with it now. But there can be no doubt that, at a time not very distant, iron, in many of its now uncontested domains, will have to pass the sceptre to another: the coming age will be the age of aluminium. It is only seventy years since this wonderful metal was discovered by Woehler, and the aluminium industry, scarcely forty years old, commands already the attention of the entire world. Such rapid growth has not been recorded in the history of civilization before. Not long ago aluminium was sold at the fanciful price of thirty or forty dollars per pound; today it can be had in any desired amount for as many cents. What is more, the time is not far off when this price, too, will be considered fanciful, for great improvements are possible in the methods of its manufacture. Most of the metal is now produced in the electric furnace by a process combining fusion and electrolysis, which offers a number of advantageous features, but involves naturally a great waste of the electrical energy of the current. My estimates show that the price of aluminium could be considerably reduced by adopting in its manufacture a method similar to that proposed by me for the production of iron. A pound of aluminium requires for fusion only about seventy per cent of the heat needed for melting a pound of iron, and inasmuch as its weight is only about one third of that of the latter, a volume of aluminium four times that of iron could be obtained from a given amount of heat-energy. But a cold electrolytic process of manufacture is the ideal solution, and on this I have placed my hope.

The magnetic properties of iron are mentioned here and attention is drawn to aluminium...

The absolutely unavoidable consequence of the advancement of the aluminium industry will be the annihilation of the copper industry. They cannot exist and prosper together, and the latter is doomed beyond any hope of recovery. Even now it is cheaper to convey an electric current through aluminium wires than through copper wires; aluminium castings cost less, and in many domestic and other uses copper has no chance of successfully competing. A further material reduction of the price of aluminium cannot but be fatal to copper. But the progress of the former will not go on unchecked, for, as it ever happens in such cases, the larger industry will absorb the smaller one: the giant copper interests will control the pygmy aluminium interests, and the slow-pacing copper will reduce the lively gait of aluminium. This will only delay, not avoid the impending catastrophe.

Aluminium is cheaper for conveying electric energy. Copper is called slow-pacing and aluminium has a lively gait....

Aluminium, however, will not stop at downing copper. Before many years have passed it will be engaged in a fierce struggle with iron, and in the latter it will find an adversary not easy to conquer. The issue of the contest will largely depend on whether iron shall be indispensable in electric machinery. This the future alone can decide. The magnetism as exhibited in iron is an isolated phenomenon in nature. What it is that makes this metal behave so radically different from all other materials in this respect has not yet been ascertained, though many theories have been suggested. As regards magnetism, the molecules of the various bodies behave like hollow beams partly filled with a heavy fluid and balanced in the middle in the manner of a see-saw. Evidently some disturbing influence exists in nature which causes each molecule, like such a beam, to tilt either one or the other way. If the molecules are tilted one way, the body is magnetic; if they are tilted the other way, the body is non-magnetic; but both positions are stable, as they would be in the case of the hollow beam, owing to the rush of the fluid to the lower end. Now, the wonderful thing is that the molecules of all known bodies went one way, while those of iron went the other way. This metal, it would seem, has an origin entirely different from that of the rest of the globe. It is highly improbable that we shall discover some other and cheaper material which will equal or surpass iron in magnetic qualities.

Can we use aluminium in our electric machinery? Notice the next sentence.

Unless we should make a radical departure in the character of the electric currents employed, iron will be indispensable. Yet the advantages it offers are only apparent. So long as we use feeble magnetic forces it is by far superior to any other material; but if we find ways of producing great magnetic forces, than better results will be obtainable without it. In fact, I have already produced electric transformers in which no iron is employed, and which are capable of performing ten times as much work per pound of weight as those of iron. This result is attained by using electric currents of a very high rate of vibration, produced in novel ways, instead of the ordinary currents now employed in the industries. I have also succeeded in operating electric motors without iron by such rapidly vibrating currents, but the results, so far, have been inferior to those obtained with ordinary motors constructed of iron, although theoretically the former should be capable of performing incomparably more work per unit of weight than the latter. But the seemingly insuperable difficulties which are now in the way may be overcome in the end, and then iron will be done away with, and all electric machinery will be manufactured of aluminium, in all probability, at prices ridiculously low. This would be a severe, if not fatal, blow to iron. In many other branches of industry, as ship-building, or wherever lightness of structure is required, the progress of the new metal will be much quicker. For such uses it is eminently suitable, and is sure to supersede iron sooner or later. It is highly probable that in the course of time we shall be able to give it many of those qualities which make iron so valuable.

Now we learn that in Tesla's opinion the future belongs to high frequency currents and aluminium. So copper may stand for low frequency alternating currents and aluminium for high frequency. Also note the phrase “Unless we should make a radical departure”. A few chapters later Tesla will describe this “radical departure”.

While it is impossible to tell when this industrial revolution will be consummated, there can be no doubt that the future belongs to aluminium, and that in times to come it will be the chief means of increasing human performance. It has in this respect capacities greater by far than those of any other metal. I should estimate its civilizing potency at fully one hundred times that of iron. This estimate, though it may astonish, is not at all exaggerated. First of all, we must remember that there is thirty times as much aluminium as iron in bulk, available for the uses of man. This in itself offers great possibilities. Then, again, the new metal is much more easily workable, which adds to its value. In many of its properties it partakes of the character of a precious metal, which gives it additional worth. Its electric conductivity, which, for a given weight, is greater than that of any other metal, would be alone sufficient to make it one of the most important factors in future human progress. Its extreme lightness makes it far more easy to transport the objects manufactured. By virtue of this property it will revolutionize naval construction, and in facilitating transport and travel it will add enormously to the useful performance of mankind. But its greatest civilizing property will be, I believe, in aerial travel, which is sure to be brought about by means of it. Telegraphic instruments will slowly enlighten the barbarian. Electric motors and lamps will do it more quickly, but quicker than anything else the flying-machine will do it. By rendering travel ideally easy it will be the best means for unifying the heterogeneous elements of humanity. As the first step toward this realization we should produce a lighter storage-battery or get more energy from coal.

This last paragraph is interesting because now the analogy is actually used to get some points across. The availability is better, as we will see later the magnifying transmitter can create high frequency currents at any location world wide. It is more easily workable, transformers do not need iron cores. And of course, high frequency currents can easily be transported to ships and airplanes. But most importantly, because high frequency currents can easily penetrate air, it is the best means for “unifying the heterogeneous elements” of our atmosphere so they can be more easily ionized.

Stay tuned, much more to come.

Thanks for sharing this piece of scientific insight. Tesla was a visionary. Unfortunately he couldn't foresee the environmental impact of the Aluminium industry:

http://www.greenspec.co.uk/building-design/aluminium-production-environmental-impact/

The coming age of aluminum holds great promise for a sustainable and innovative future. This lightweight and versatile metal is increasingly being recognized for its abundant availability, excellent recyclability, and remarkable strength-to-weight ratio. See this krcaluprofiles.com/product-category/aluminum-profiles/ for more interesting ways about Aluminum products. From transportation to construction, aluminum is set to revolutionize industries, offering energy efficiency and reducing carbon footprints. Embracing the potential of aluminum will shape a greener and more resilient world.