Tree of Life: The Fascinating Journey of Placental Evolution

Please feel free to check out my previous post first, from which this post was spawned

(This post gets increasingly interesting the further down you read, so I highly encourage you to get through it all despite its length!)

This is the least disgusting image of a placenta I could find... honest Credit (labeled for reuse but details unclear)

Recap

Two weeks ago, I covered the next stage in evolution that finally took us to the familiar branch of life that dominated the earth (at least visibly to us) today: Mammalia. This process required us to get up onto land and develop an intricate system of eggs that, rather than happened out of necessity, occurred from the rise of opportunity afforded with land-based egg-laying.

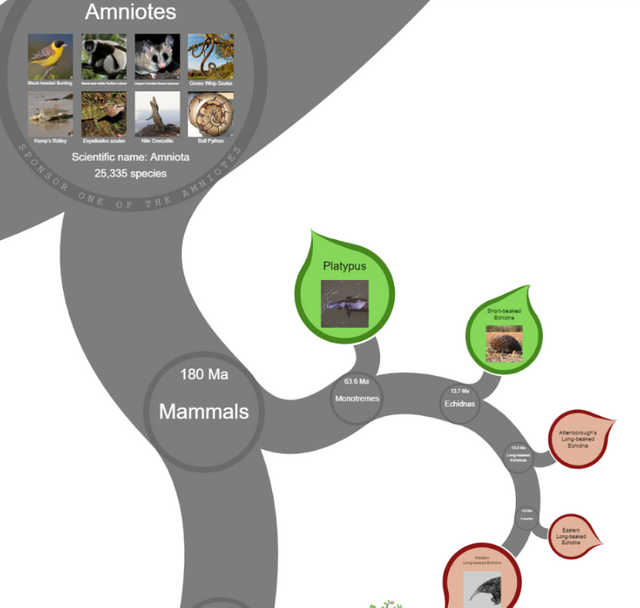

But Mammals don't lay eggs; our eggs are internal, something that, as we learnt, has pros and cons depending on one's environment. It turns out most mammals found it far more beneficial, but there were some early exceptions that live on to this day; Monotremes

To this day we only know of two extant species of monotremes; the platypus and the echidna - both of which are egg-laying mammals. Out of mild interest, one of the extinct echidna is named after my (and almost everyone's) hero, David Attenborough, the Zaglossus Attenboroughi. Good luck pronouncing that.

Monotrema broke away from our branch almost 64 million years ago and have remained largely unchanged since... I guess. But that still leaves over 5,000 known species we have to sift through. Now, there are 3 group-types of mammals. Marsupials and Monotremes are two already discussed, and the other is the theme of today:

The Placental Mammal

Now before we get into what, how and why, we need to look at when, which is a surprisingly difficult question given that placentas don't typically fossilize well. In fact, the disputed claims overall seemed to have concluded their evolution around 100 million years ago, before the big asteroid that at least contributed to the death of the dinosaurs.

But a recent look into this from 2013 settled this debate a bit more concretely. Nowadays, it's a lot easier to process huge sets of data, meaning large, all-encompassing sets can actually serve a practical purpose rather than getting lost in in its own complexity. With that in mind, the study lead by Maureen O'Leary constructed an overly detailed placental family tree:

The team's database included more than 4500 characteristics for each of 86 species. They chose creatures that represent all major groups of placental mammals, which vary in traits such as size, fur color, and various other aspects of anatomy and physiology, including the number and arrangement of bones and teeth. They also compared 27 different genes common to all placental mammals. Source

They found that the earliest placental ancestor appeared a little under 400,000 years after the mass extinction events. The animal in question is unknown but based on assumptions following the family tree down, the pattern would suggest:

...a tree-climbing, insect-eating mammal that weighed between 6 and 245 grams—somewhere between a small shrew and a mid-sized rat. It was furry, had a long tail, gave birth to a single young, and had a complex brain with a large lobe for interpreting smells and a corpus callosum, the bundle of nerve fibers that connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain.

How Shrewd. Credit: Yathin sk CC 3.0

So how did we get from those little shrew-like, egg-laying monotremes to a complex placenta-fed, embryo-wielding (or eutherian) mammals? Well, the embryo is basically a glorified egg, thinned out into a membranous goo. In the early days, the uterus served to feed calcium to the embryo due to this shortcoming that occurs when you lack eggshells, thus creating the earliest stage of a placenta.

But this idea, that was discussed in the last episode, was super basic and it was the marsupials that really evolved a more developed, yet still simple and short-lived version of a modern placenta called a Choriovitelline placenta. In their very short pregnancy (with the rest happening in pouches or whatever dumb method they went with), it's the marsupial's yolk sac that functioned as the placenta while still attached to the mother, allowing a smooth stream of nutrients, rather than dumping everything in a one-time calcium prison. This generally wasn't sufficient in its basic form though, hence the early birth of marsupials that depend then on super special milk.

Modern fully placental mammals did away with useless egg sacs - they are still there, but more or less vestigial - and instead utilised and re-purposed the equivalent parts of the complex eggs used in the rest of the land animals at this point; the chorion that previously lined the egg shell to allow gas exchange became the placenta, and the allantois eggs used to use as a waste depository became... can you guess? ... The umbilical cord!

The body's way of repurposing old material is something I really need to start applying to my own creative workflow.

Ok but... how, really?

This point in the post is a great opportunity for 'Intelligent Designers' to jump in and point out that the placenta has no mechanism to have evolved from, no intermediate form. As I said, the placenta doesn't fossilize well and if nothing else, is an incredibly complex organ. But is it unique?

No, not even a little. Mammals have indeed only ever evolved the placental design once, which makes it hard to trace back historically. But the idea of a placenta has evolved 132 known times in nature as similar pressures of environment drive convergent evolution. Reptiles alone have evolved placentas at least a dozen times and 1/5th of lizards and snakes have committed to live births. Even sharks and some small fish have evolved placentas no less than 8 times, such as poeciliids, which include guppies. Most of these are of course different in form to the mammal version, but clearly all serve the same purpose.

In fact, the intricate system thought to be unique to mammals allowing nutrients from the blood of the mother to pass to the child turns out not to be unique either. A discovery in 2011 showed that the lizard Trachylepis ivensii. (a skink, again) actually managed to evolve a 'true' placenta just like our own.

Clearly, even if we couldn't answer the how truly, it was hardly a difficult concept for nature to build. But let's give it a shot anyway. And this gets really interesting:

In Brief

The problem with most placenta designs is that they cannot get a rich flow of nutrients from anywhere because they're surrounded by a modified egg shell, so they have to depend on the yolk sac that you find in any regular egg. The mammalian (and skinkian) change came when cells on the outside of the embryo kind of had enough and started getting aggressive with the mother's oviduct wall.

From Lord of the Rings

From Lord of the RingsLike that scene from Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers where the Uruk-hai put giant ladders upon the walls of the castle, the outer cells of the embryo reach out and penetrate the oviduct wall and push through, where it continues to produce cells, or Uruk-hai at the top of the ladder. With enough cells having penetrated the mother's defenses, they ycan now push up against all the blood vessels and steal the necessary loot of nutrition.

It's possible that this model has occurred up to 3 times in skinks, giving us a total count of 4 that we know of. Remember, none of the materials appeared from nowhere and simply developed from earlier stages... kind of.

More re-purposing

As is often the case, a system or organ or cell or other function of the body can be used for multiple purposes. One gene that codes to make you blink may also be used to, say, make you itch. There's often no pattern to their connections, at least easily recognisable.

In this example, the CDX-2 gene is primarily known for its role in the development of the gut and intestines of vertebrates. But it also turns out to play a role in the development of the placenta. Various mutations of these genes allow them to be borrowed by the placenta, along side a whole bunch of other re-purposed genes. But evolution isn't going to give us a break just yet:

Retroviruses

Credit Periwinklemoose11: CC4.0

This is where things get really complicated for nature. Not everything in evolution is so elegant to the point that it seems to have purpose. This is a whole post in itself, but 10% of our genome consists of retroviruses, and some of these are beneficial, even vital to the development of certain systems. In the case of the placenta, ancient retroviruses used proteins to help them fuse and infect a host cell.

These proteins however were inadvertently repurposed when the placenta, unlike the embryo, allowed access for the retrovirus allowing the proteins to take action, but by fusing cells of the fetal tissue around the mother's blood vessels.

Millions of generations over millions of years would have been needed for such incredible synergy, symbiosis and internal battles (literally) to end up developing something so complex and complete as a system of live birth. So it's a good thing the Universe happened to provide us with all the time in the world (...literally) to get it done. Hundreds of times over.

Again, trade-offs were made, but this allowed a more intense intake of nutritious resources and thus complex organisms, bigger brains and more. Take a minute to appreciate the warzone that went on inside your mothers' wombs, and their mothers, and ancestors for millions and millions of years. What a hellish existence we live in!

References:

Ancestor of All Placental Mammals Revealed | The Placental Mammal Ancestor and the Post–K-Pg Radiation of Placentals | Choriovitelline placenta | Placenta Evolution and a Sexual Cold War | The marsupial placenta: a phylogenetic analysis. | Review: Marsupials: placental mammals with a difference. | Zoologger: The first reptile with a true placenta | REPRODUCTIVE SPECIALIZATIONS IN A VIVIPAROUS AFRICAN SKINK AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR EVOLUTION AND CONSERVATION | Demystified . . . Human endogenous retroviruses | Expression of Cdx-2 in the mouse embryo and placenta: possible role in patterning of the extra-embryonic membranes

This is a brilliant piece and was totally unaware of your presence among us up until now!

Fully upvoted and following from now on.

Namaste :)

I keep fairly quiet =P Thanks for the up/follow! Much appreciated having actual real users follow for a change =D

Hello @mobbs

Very detailed historical account of development of placenta!

It is interesting to get to know the different stories of nature inspired tinkering and manipulations that eventually give rise to what we have today. Who knows where these ever dynamic processes are headed? Evolutionary forces may one day tinker with what we have today...or what do you think?

Regards

@eurogee of @euronation and @steemstem communities

Oh evolution hasn't stopped nor slowed down. We just can't tell because it's such a slow process over millions of years. We are definitely changing! Maybe we'll start laying eggs again in the future...

Did I hear you say lay eggs??😰

As a mother I think laying an egg would be sooooo much easier ;P

what makes me plague?

You steal content from my buddy = time to get a new account if you want to continue your fraud - until that account gets ruined too. Good luck!

That Lord of The Rings reference used to describe the process where the outer cells of the embryo penetrate the mother's oviduct wall is gold.

Heh, first thing that came to my head, not sure why. Just seems like babies are trying to kill their mothers from the day of conception!

It's a cruel world!

Highly Educative post most times are lenghty but information contained therein are just worth learning.

Placenta plays a very significant role in the development of a a foetus, its function is quite enormous thus, placing it at the forefront of protecting the foetus or embryo undergoing developmental stages

This is a beautiful piece @Mobbs

Yeah this was a bit longer than I'd have liked but I didn't want to cut it short... Cheers!

Wow! There are actually some egg-laying mammals around? I'm sure they would be looking so crude and funny. (platypus and his brother).

Now I have to unlearn somethings I know about mammals.

PS: that "Attenboroughi" sounds like an incantation.... I'm kidding

Nice piece buddy

There are egg laying mammals, live-birthing reptiles and fish, and everything in between. There's an exception to every rule, it seems =) Thanks for dropping by again!

Excellent post!

No man's land!

I suppose technically it's 'One man's land', right?

Haha!

Hi @mobbs!

Your post was upvoted by utopian.io in cooperation with steemstem - supporting knowledge, innovation and technological advancement on the Steem Blockchain.

Contribute to Open Source with utopian.io

Learn how to contribute on our website and join the new open source economy.

Want to chat? Join the Utopian Community on Discord https://discord.gg/h52nFrV

Hmm.... Egg laying mammals??

May I ask what makes them mammals if they lay eggs?? Your posts are always really educative.. Never knew this at all...

Two things define them specifically I think: Nurture with milk (the egg laying monotremes still do this in a different way) and hair/fur. There are bound to be exceptions to all of these things though, probably! Generally you should tick a few boxes to be classified

Yeah Yeah... You should tick a few boxes to be classified as a member of a group and only the egg laying factor is not enough to disqualify them from being classified as mammals...

Thanks for the clarification...

Masterpiece. I like how you managed to correlate it with the LOTR series :)

Heh, masterpiece is a strong word =P

Nah, this post deserves it :P