Ideological Failures at Addressing Climate Change

Your preferred ideology isn't going to do a damn thing to adequately solve climate change or climate change related issues. Capitalism, communism, Christianity, atheism, libertarianism, liberalism, conservatism, and any number of other -isms entirely fail to adequately address the oncoming disasters. This is partially due to the anthropocentric nature of most major ideologies, but more importantly it results from the tendency of most ideologies to use problems they're nominally trying to solve as ammunition to further their own continuation instead. Environmentalism is the only ideology that can really do much about this, but even many flavors of environmentalism itself fall into these traps.

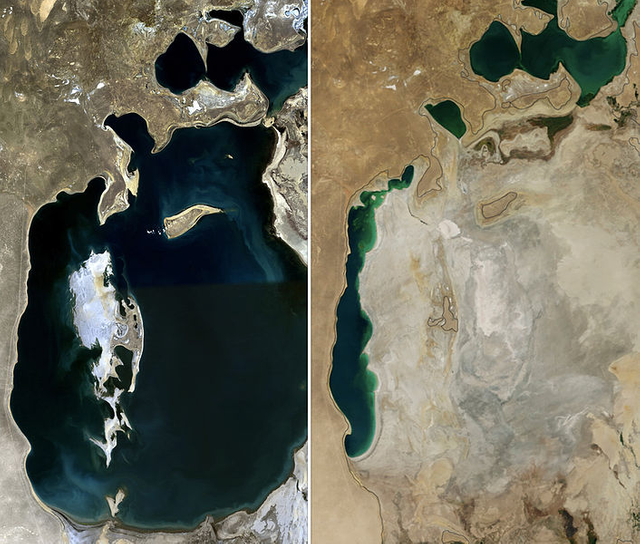

Left: The Aral Sea in 1989, already much reduced to a fraction of its former size by Soviet public works projects. Right: The Aral Sea in 2014. The intervening regime change hardly slowed its shrinkage [Image source]

We can see clear examples of this throughout history. During the Cold War, both America and Russia committed countless environmental atrocities. Russia had Chernobyl, the drying up of the Aral Sea, and countless more environmental disasters. America polluted rivers until they caught on fire, spilled oil repeatedly in sensitive environments, and did their best to match Russia disaster for disaster. Almost everyone critically over-stressed their water resources and built environmentally disastrous dam after dam. When examining the environmental records of countries in that time period, there seems to be little to no correlation between government type and environmental record. The Dominican Republic, a brutal and murderous dictatorship at the time, actually had one of the best environmental records of the twentieth century.

This isn't to say all ideologies are equally bad or good for the environment- some are, in fact, significantly better or worse at carrying out environmentally friendly actions than others. This is, however, less attributable to their own insintric traits than to other factors most of the time. Environmental protection efforts often do better in intellectually heterogeneous climes. This can again be illustrated using an example from the Cold War. During the Cold War, environmental history simply wasn't a discipline of academic study. It wasn't until the end of the Cold War that it bloomed, despite the existence of all the data it needed to blossom significantly earlier. The British historian Bruce M.S. Campbell puts it best in his book The Great Transition: “...the long dominance of anthropocentric analyses grounded in either Marxist theory or neoclassical economics means that scant attention has as yet been paid to the historical roles of environmental processes and forces.” Neither ideology could tolerate any view of the universe that didn't revolve entirely around mankind, and tended to quash any competing ideas. Environmental history's blooming happened almost immediately following the end of the Soviet Union.

The Fall of the Berlin Wall. [Image source]

As pointed out by Campbell, ideologies derived from economics tend to be by far the worst offenders. Courses of action that aim for a strictly economic goal simply will almost never work in the environment's favor, whether said economic goals are profit related or otherwise. There's a long, long list of reasons why: the tragedy of the commons, the persistent shortsightedness of human beings, the greater profitability of greed, and the preference for immediate gratification are just the tip of the iceberg. While ignoring economic goals is an absolutely disastrous course of action for a nation, they need to be balanced carefully against environmental goals. In addition, economic rationales for environmental plans pose significant risks of corrupting and derailing environmental plans.

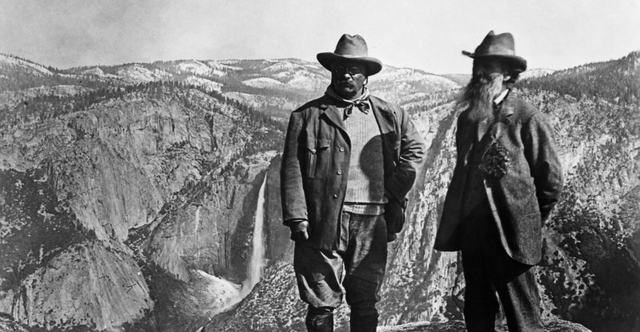

For most ideologies the problem isn't as clear-cut as it is with economic ideologies. Take American liberalism and conservatism, for instance. The frequent claim of the American left is that the right is intrinsically bad for the environment. In defense of the left's argument, the right is rabidly opposed to a number of environmental policies, and often even entirely denies the existence of climate change. This is not, however, due to some in-built quality of the right. It actually is the result of a deliberate political shift on the part of the right in the early 90s. Led by Newt Gingrich, the architect of so many modern ills, the Republican party moved away from supporting environmental causes as a way to rally their base- environmentalists made convenient foes to circle the wagon against. Prior to this, environmentalism was an entirely bipartisan movement. The American president who did the absolute most for environmental causes was Teddy Roosevelt, a Republican.

Teddy Roosevelt posing with John Muir in Yosemite. [Image source]

When we examine the left's screeds against the right's treatments of environmental issues, a common underlying thread pops up again and again. They are, much of the time, advocating more strongly for people to join the left with its stronger environmental credentials than actually advocating for environmentally sound action. This isn't unique, either- every ideology that supports environmental causes bashes other ideology for being less supportive of environmental causes, then advocates joining them as an environmental solution. Advocates of Scandinavian style socialism, for instance, frequently neglect to mention how much of the Scandinavian economy is built on oil revenues when touting their environmental accomplishments.

The philosopher Karl Popper gives us a useful framework here. In one of his books, The Poverty of Historicism, he divided social planning into holistic and piecemeal planning. Holistic planning to Popper was the act of planning out a society with a specific goal in mind, and redirecting all efforts to force society into that plan. Piecemeal social planning still often had a goal in mind, but was quite comfortable just treading water while they fixed a few problems if need be. Even more importantly, piecemeal planning anticipated unexpected results, while holistic planning tended to expect everything to go according to plan.

Popper's essay was, of course, an attack on Communist social planning, but it taps into something important. Societies, like the environment, are exceptionally complex, non-deterministic systems. If you were to create a thousand such complex systems all with absolutely identical starting conditions, you would get a thousand incredibly diverse results. Running the same experiment again would never result in a repeat.

Most ideologies have very specific goals and preferred methods. In essence, filtering environmental planning through most ideologies has the effect of turning it into holistic planning. If we want to succeed at mitigating the worst damage to our global ecosystem, we need to act in a piecemeal fashion. There is no one single solution to our problems- it's going to take an ugly, stitched together collection of thousands of makework solutions, stopgaps actions, and frantic delaying attempts. We have to adapt our thinking to complex systems that interrelate, act unpredictably, and feed back on one another. We have to work on thinking scientifically. No ideology is going to solve our environmental problems- only by focusing directly on those problems and ceasing trying to use environmental issues to score points for our ideologies are we going to make any progress. The only way to win as a planet is to keep our eye on the ball. In the end, we're all on the same team.

I'll be returning to my series of posts on the Holocene Extinction tomorrow- for now, had to get this rant out of the way.

Bibliography:

Selections, by Karl Popper

The Great Transition, by Bruce M.S. Campbell

Collapse, by Jared Diamond

Environmental Problems of the Greeks and Romans, by J. Donald Hughes

The problem with ideologies, religion included, is that they tend to settle into entrenched bureaucracies, carving-out departmental fiefdoms. In a sense, like the planet has a complex interaction with life and life with the planet, the entrenched bureaucracy necessitates the continued persistence of the problem/issue it was designed to resolve. In an entrenched bureaucratic fiefdom, the incentives are perverted to not only maintain but exacerbate the issues/problems, since worsening situation justifies increase in funding, with which the bureaucrats can increase their influence and power. The property functioning of government requires a vigilant and ruthless mind, who can bring down the iron fist, when certain departments amass too much power without any results. Representative democracies are notoriously poor in reigning-in bureaucratic excesses, due to its ludicrous political structure.

The First Law of Bureaucracy: The survival of the bureaucracy must come first, even beyond the bureacracy's stated purpose.

The Second Law of Bureacracy: The bureaucracy must seek additional funding, jurisdiction, personnel, and power, even beyond reasonable levels.

The Third Law of Bureaucracy: Exacerbating or failing to solve the problems the bureaucracy is tasked with solving or managing can act to grow the need for, and thus the power of, the bureaucracy.

Can you think of any more?

It is like a parasite, but less fit to survive than those that inhabit animals and humans. Bureaucracy is like the ravenous filarial worms that kill the host outright, rather than flatworms that take what they need without depriving the host of too much resources. Unchecked bureaucracies tend to expand to the limits of resources a society can provide, then begins to cannibalize the very host till both the society and the bureaucracy are no more. Yet, structured and ordered means of social regulation is necessary to prevent a community from degenerating into tribal cannibalism. A well-functioning bureaucracy ought to function as a parasite that limits unchecked growth of certain human tendencies that are ultimately destructive to mankind in general; the parasite, in turn, need to be checked, so that it does not kill the very society from which it feeds.

Great post! I've been meaning to leave a comment on it. It is interesting how political ideologies create a wedge issue when it comes to a proper discourse to solving not only global warming, but sustainable energies in general. I consider myself to be a moderate overall and my belief is that in order to usher in a age of environmental awareness and sustainable energies, we will need the help of big money or corporations; specifically for future developing of certain technologies. I've gotten into many arguments with my Republican friends when I mention that oil is a terrible resource for energy– it's unnatural, finite, destroys environments and is the leader in green house gas emissions. When I was a kid I went deep sea fishing with my dad. We were about 15 miles off shore and when I looked back towards land, you could see this noticeable black bubble hanging over the cities. I'll never forget that as evidence that pollution is a very real threat to our wellbeing.

Good post. Some minor things:

Folks not reading your essay closely may take from this that all ideologies are equally terrible at managing environmental issues. That is baloney. Ideologies favor different governmental forms, and some governmental forms have mechanisms for managing the commons (democracy, autocracy), while some mostly don't (plutocracy, adversarial anarchy).

Teddy Roosevelt, like Lincoln, was a left wing progressive. By the time Teddy Roosevelt took power, the Republican Party has already started to drift rightward, and was ideologically mixed.

Norway's economy is substantially boosted by hydrocarbons. This is not the case for the rest of Scandinavia.

All fair cops! I should note that this is definitely targeted primarily at the "replacing capitalism with socialism will cure our environmental ills" crowd, so I intended the message to be a little blunt.

As a socialist myself, I agree, though maybe for sightly different reasons. For example: Washington State almost passed a carbon tax (basically the only realistic way to tackle climate change under modern regulated capitalism), but it was opposed by the left for not being the result of a justice-oriented process or something like that. The leftward part of the coalition that stopped the tax from being passed revealed where the environment falls in their priorities by doing so.

Yep! Exactly the sort of stuff I'm talking about.

We are slowly killing our own planet. Yet our governments and it's leaders still turns a blind eye to this issue. Why? Because of fucking profits that's why! If no action is taken soon, we better start looking for another planet to live in, cause earth itself won't tolerate us any longer. Thanks for the great post.

Thanks for reading!

Great Post!

It’s an issue no one can ignore, but the greed for profit is blindfolding everyone.

Very true!

Simple freedom is the only solution; and it goes hand-in-hand with what your saying. Perhaps this is libertarianism, but I don't necessarily think about it in those terms. There's no single solution to our problems, especially environmental ones, so why not just let people try different things and see what comes out of it? Experience tells us it's the only thing that works in the long run.

The tragedy of the commons argues otherwise. What's good for the individual is not the same thing as what's good for society- societal gains result in lesser gains for individuals quite often.

The thing with the tragedy of the commons I never understood is how can you know what is better for the "greater or common good"?

If societal gains result in lesser gains for individuals then how is it good for society, which is nothing but a collection of individuals? Seems like this is based on a utilitarian assumption.

Well, take a look at the classic example that the tragedy of the commons is named for. Medieval English villages had a commons, or common green- a place where villagers could graze their sheep and cattle and the like when their pasturage was getting a little low on feed. The strategy that makes the most sense from an individual level is to exploit the commons as much as possible, which when everyone does, the commons is denuded and destroyed. (As happened often.) When, instead, the village controlled more strictly who could use the commons to prevent overgrazing, it became much more useful over the long term, benefiting more people. Admittedly that benefit was by a smaller amount than would be received by short term exploitation- but it lasted much, much longer, and that adds up in the end.

I see what you mean by exploiting the commons as much as possible for individual gains, but this is short term thinking. In the long run if individuals exploit the commons as much as possible there would be no commons later on to benefit from.

OK, so if this control is based on each individual agreeing that the village should be able to regulate the commons, this is not mutually exclusive toward free association or self-governance. The problem occurs when people are forced to abide by certain controls without any chance to opt-out or the possibility of reforms within the village.This is when some individuals start to get greedy and exploit as much as possible, sort of like blowback causing the classic tragedy of the commons.

If there's one thing that history shows, it's that individuals almost never think in the long run- they always exploit the commons until it's destroyed unless restrained by social mores or government restrictions or the like. You can only reasonably expect someone to think in three generations- their parents, themselves, and their grandchildren, and even that's too much to ask from a great many people. And as for having opt-out from the regulations governing the commons- the only reason to opt out would be to exploit said commons beyond fairness. This is, essentially, how the needs of society and the individual diverge. To put it in utilitarian terms, the needs of society provide for individuals, but do not maximize their gains. It is in the best interest of the individuals to maximize their gains, but that is often harmful to society at large in many situations.

I won't disagree with that, the masses of humanity definitely are short-termers best suited for collectivism; although it's sort of unfortunate for those rare individuals who are not like that and have to face this burden of sacrificing their autonomy.

Well, you also might want to opt-out because you don't think the the authority behind the commons is being organized fairly.

I think the crux of this issue is whether or not the individual is more important than the collective. Personally, I believe in freedom regardless of the utilitarian benefits or disadvantages; history has also shown that "society at large" has been responsible for death and misery for millions of people, while individuals have been behind innovation and art that have bettered humanity.

It unbelievable how hypocritical some countries are calling for issues such as climate change and actualy do the opposite for profits.

Left and right should meet in the middle. Not that both sides are wrong, but mainly that both sides are right.

Great post!

Resteemed!

@originalworks

I'm confused - isn't 'environmentalism' in and of itself anthropocentric? I'm no geologist, but correct me if I'm wrong - wasn't planet earth a toxic wasteland of poisonous gas and lava for almost all of its existence? Why would it suddenly care whether it was a hospitable environment for humans to live on?

The answer to that is actually pretty complicated. Long story short: The current shape of the earth is basically determined by life. Plate tectonics requires water to lubricate it, life keeps water around. The actual structure and behavior of the planet itself is, to a great extent, dominated by life. And it was only a toxic wasteland of poisonous gas and lava for a relatively short period of time- less than half a billion years before the surface cooled and oceans formed. So in a strict sense the Earth doesn't care- but in a more causal sense, it sorta does.

Also, you should post replies to the actual post, not to a random comment on it. :D

the problem.. https://steemit.com/steemit/@alexalpmarket/hello-to-all-my-friends-of-steemit-youtobe-vs-dtube