Philosophy of Science Part 1: The Bugbear of Teleology

Though I haven't yet finished my Geology and Civilization series, I'm getting an early start on my next series- mostly because I just felt more inspired to write this today. This probably won't be a series I update on a regular basis, but rather sporadically as I feel interested. Philosophy of science is a subject I'm quite interested in, as in its best moments it offers scientists insights into how they can better function as scientists. Of course, much or even most of the time it merely serves to explain how scientists do what they do- it's quite normal for a scientist encountering some idea within philosophy of science to think it perfectly obvious, and even question why it needed to be explained. So philosophy of science is more useful, most of the time, to philosophers and interested laymen. Still, however, those occasional gems make it well worth exploring. Today we're going to dive into an idea that can do a lot of damage when it infects scientific thought- Teleology.

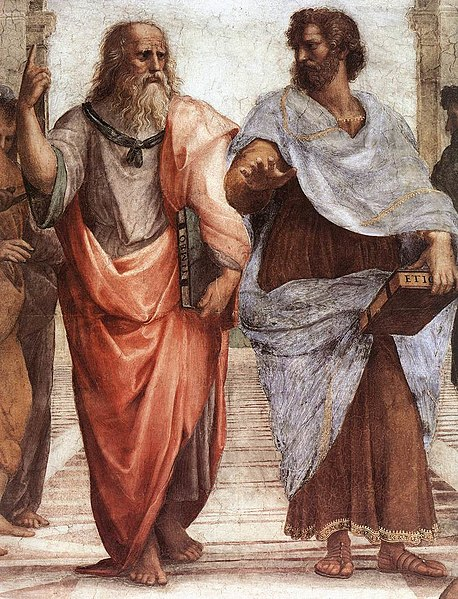

Plato and Aristotle were both proponents of natural (intrinsic) telos. [Image source]

Teleology is, in simplest term, the study of something's purpose. It comes from the Greek word telos, which literally translates to end, goal, or purpose. Telos is a little deeper than just that, however- it is the reason for the entity in question's existence. (-ology comes from logos, which translates to reason or explanation.) There are two main types of telos- extrinsic telos, which is imposed upon an object, as we do upon clothing when we create it, and natural teleology, which claims that natural entities have intrinsic telos. It's the latter that one we're concerned with at the moment. (Extrinsic teleology is relevant to science as well, but in a very different way- one that the following criticisms of teleology don't really address.)

So why is insintric teleology such a threat to science? Let's turn to the prominent paleontologist Richard Fortey real quick.

"I must mention the bugbear of teleology- ascribing purpose to all evolutionary activity, as if the whole of creation were striving for perfectibility."

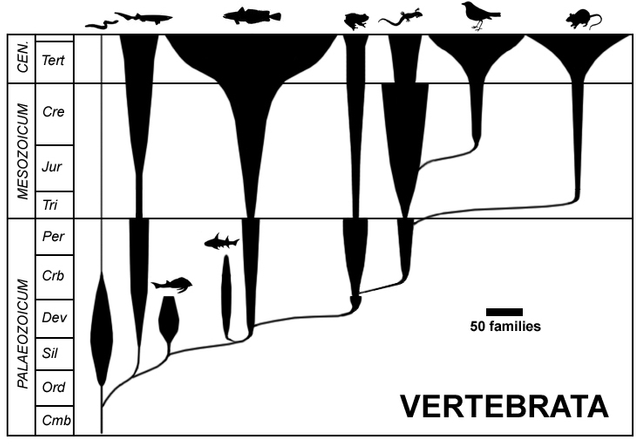

This is where our title comes from, but it sums up the problem pretty specifically- teleology tends to, when it permeates science, generate motivation for processes that lack them. Quite a few people, including those Victorian scientists that I complain about so much, have claimed over the years that mankind was the inevitable result of evolution, that nature (or God) used evolution as a tool specifically to create us. They made us the telos of nature and evolution. The problem is that we're not by any means an inevitable result of evolution.

The vertebrate branch of the evolutionary Tree of Life in the form of a spindle diagram. [Image source]

This isn't to say that evolution is random- it is, rather, contingent. The state in which the world rests today is the result of everything that came before it, in a long sequence of actions and reactions- but if we were to rewind it back in time and replay again, with no changes made, we'd have no guarantee of what resulted, even with that identical starting state.

Teleology has a tendency in historical studies to bring about a vision of historical eras as internally homogeneous. Take the 14th century, for instance. We usually tend to call it the end of the medieval era, but even within Europe it was a mishmash of medieval and more modern ways of life. In France and Spain feudalism still ran strong, while many city-states elsewhere in Europe, such as those in the Hanseatic League, were recognizably modern in many respects. Despite the height technological civilization has reached today, hunter gatherer societies still exist. Teleological thinking most obviously is applied in Marx's material dialectic, but shows up in Fukuyama's "End of History" ideas as well, and Fukuyama is a fierce foe of communism in many respects. This tendency of teleology to reinforce conceptions of various eras applies in science as well. When we're looking at an era, whether historical or geological, it will of necessity be internally heterogeneous, yet we so often tend to think of it as homogeneous. Anachronism is a fact of daily life.

Whether teleology inevitably results in this internal homogenization of our conception of eras of time or not is a question up for grabs, but it's clearly common enough that we have to take it seriously.

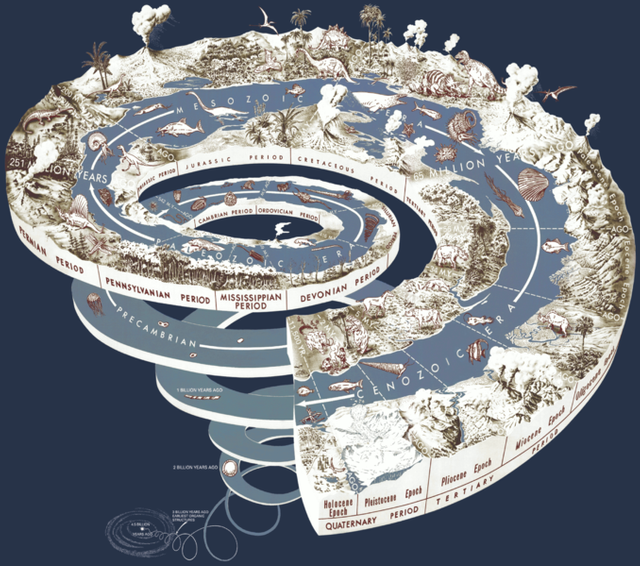

The geological history of the Earth. [Image source]

One of the main ways in which we distort our perception of past eras is in the comparison of how we think of their endpoints. The beginning of the Jurassic has much less in common with the end of the Jurassic than it does with the end of the Triassic, the era before it. While the endpoints we assign to various time periods are often accompanied by severe, even catastrophic change, that level of change seldom affects the world on a universal level, and is usually (though not always) dwarfed by the changes that accumulate gradually through time. The beginning of one period will almost always have more in common with the end of the previous period than with its own ending.

Teleology also affects our way of thinking about the transitions between various eras as well. It's easy to think of the transition between a hunter-gatherer society and an agricultural society as inevitable steps in the ladder of progress, thanks to the way teleology tends to infiltrate our thinking. The physicist and hydrodynamicist Arthur Iberall (who was also critical in the creation of working space suits) came up with an interesting counter to this problem. Iberall chose to reject the image of the ladder of progress, instead treating the major transformations in human history, like the one to agricultural civilization, as critical thresholds instead. They were the point where quantitative changes in society, like greater knowledge about plants in the agriculture example, became qualitative. This mode of thinking is clearly applicable to science as well, though some modification is necessary in different fields. In geology, for example, our tendency to delineate many of the major transitions between eras via major catastrophes seems to pose a problem, but Iberall's idea doesn't actually require us to think of the accumulating changes as happening at a regular pace, which would be absurd- most change in nature occurs at an uneven rate.

The philosopher Hegel often discussed matters of teleology. [Image source]

Contingent views of history and critical thresholds are useful tools in avoiding teleological thinking, but one must be cautious of teleology's close ally in science- scientific positivism. It might seem weird to criticize positivism, a philosophical school that holds that scientific knowledge is the only valid knowledge, but they also have often held the position that scientific knowledge can only come from the or positive affirmation of scientific theories through the scientific method. It's the positive affirmation bit that's problematic on a few levels. It runs a little counter to the spirit of falsifiability, the heart of modern science, but there's a more important level it causes problems at- it tends to result in real field data being ignored when it runs contrary to established scientific theory.

One of the best examples of this is J. Harlen Bretz and his discovery of the Missoula Floods. (They're often called the Bretz Floods as well). At the time, the dominant geological theory was uniformitarianism- the idea that the same forces active in the present shaped the past. While this was largely true, the history of uniformitarianism, which I've written about before led geologists to firmly reject any claims of colossal past catastrophes. While J. Harlen Bretz would eventually be vindicated, proving that the massive flood from a collapsing glacial lake had torn up the landscape from Montana to the Pacific, it took decades of battling established scientists to do so. It was a battle that continued until the discovery of the meteor that killed the dinosaurs finally forced uniformitarianism into a synthesis with catastrophic events of the past. (In part, this involved a reworking of how geologists understand time, specifically the present, but that's another story.) And, to be clear, this story isn't just saying that these uniformitarians has positivist tendencies- their faction was often actually referred to at the time as the Positivists. (Bretz belonged to the Pragmatist.)

Dry Falls, a geological formation in Washington State formed by the Missoula floods. [Image source]

While positivism and teleology often come from quite different places, they both represent a tendency to try and attribute logical human order to the world around us. The world, human civilization, and humans themselves, however, seldom want to behave in a logical, orderly fashion. The world is a fundamentally messy one, and science must understand and respond to it as such. Many of the greatest evils science has produced have come from attempting to force people- or nature- to conform to our theories. (Psychiatry provides plenty of great examples.) We must adapt to the world's vagaries, not the other way around.

Bibliography:

Hi @mountainwashere!

Your post was upvoted by utopian.io in cooperation with steemstem - supporting knowledge, innovation and technological advancement on the Steem Blockchain.

Contribute to Open Source with utopian.io

Learn how to contribute on our website and join the new open source economy.

Want to chat? Join the Utopian Community on Discord https://discord.gg/h52nFrV

Wow, our upvotes are big now, lol. Anyway I just wanted to point out what the other commenter did:

I get particularly frustrated by the arrogance of mankind. Calling is the inevitable result implies we are the result, the end, the finale conclusion.

This is dumb not only because we're still evolving, but so is everything else. Chimps aren't behind us evolutionarily, they're alongside us, perfectly adapted to a different lifestyle. It's not like their genes are more ancient than ours.

I'd argue something like wheat or grass on the whole, or mites, or ants dominate the earth just as much or more so than us. Is wheat the inevitable result of evolution?

Yeah, your upvotes are definitely getting pretty huge. Definitely not complaining, though. :D

The fact that we're still evolving was the whole reason for my rant about the paleo diet the other day- while it's not actually a bad diet, it's entirely based upon the idea that we've stopped evolving.

In fact, I actually think that speaking of evolution as progress at all is quite harmful- take living fossils like the coelacanth, the opossum, or any number of other species that have maintained fairly stable forms for eons, with little adaptation necessary to survive in their niches. They are, in this sense, "less evolved", but that makes them by no means less well adapted to survival. Evolution isn't the goal for a species (for that to be true brings in yet more teleology)- it's just a means to survive.

And wheat definitely isn't- especially considering that we've bred it into functionally whole new species. And, since while culture, language, technology, and society can act upon evolution, they themselves aren't a subservient category to evolution itself, so wheat's nearly as far as you can get from an inevitable result of evolution.

Great post as always @mountainwashere! Keep up the good work.

Keeping critical is key to the big picture. Many many scientists in human history proposed wild theories (e.g. plate tectonics) that many outright rejected.

Conforming to theories did not work for them and some of them suffered (e.g. Alfred Wegner).

In 1926, over ninety years ago W. M. Davis wrote about "THE VALUE OF OUTRAGEOUS GEOLOGICAL HYPOTHESES".

He basically argues, well ahead of his time that being very open minded and not being afraid to re-address long standing theories are key to evolution of thought. Here is a link to his paper below. Keep up the awesome work! The world is strange and we have a long way to go until we "figure it out"...

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjUxu6r1qvbAhVEl5AKHUH1CvUQFggmMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fpages.mtu.edu%2F~raman%2FSilverI%2FMiTEP_ESI-2%2FHypotheses_files%2F1926-Outrageous.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3XOk11_cLadd57XEDZttgJ

Oooh, thanks, excited to read it!

No worries. Thank you and hope you enjoy more philosophical insights that this paper (and your post) provides!

Gem:

Hah, thanks!

I guess these societies never evolved:)

This really sums it up

Remaining stable in one form is as much a part of evolution as changing form is- if your current form is optimized for your ecosystem, why mess with a good thing?

They often say to move forward, we should look to our past. I feel rather than looking, we shoudl learn to mend our habits to those of the people whom never had much but was still satisfied, hopefully one day that will happen. Overall thou, really good read :)

You received a 80.0% upvote since you are a member of geopolis and wrote in the category of "geology".

To read more about us and what we do, click here.

https://steemit.com/geopolis/@geopolis/geopolis-the-community-for-global-sciences-update-4

Congratulations! This post has been chosen as one of the daily Whistle Stops for The STEEM Engine!

You can see your post's place along the track here: The Daily Whistle Stops, Issue #151 (5/31/18)

The STEEM Engine is an initiative dedicated to promoting meaningful engagement across Steemit. Find out more about us and join us today.