"Majority is an expression of force, not rationality"

Winston S. Churchill said that “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.”

The notorious Brazilian writer Nelson Rodrigues said that: "All unanimity is dumb. Those who think with unanimity need not to think."

Whenever I have to make decisions that affects other people, I inevitably spend sometime thinking about the democratic decision making process itself.

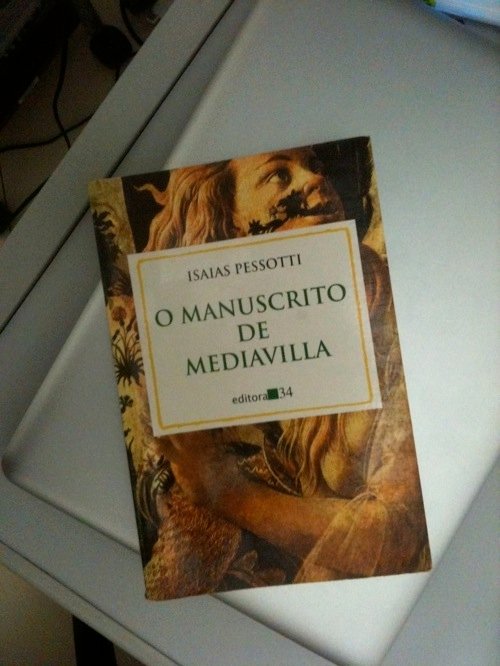

And the more I read, learn and think about it, the mor I like the (not really a) definition given by professor Isaias Pessotti, a psychiatry professor at the University of São Paulo that studies the history of madness, in his second novel, The Mediavilla manuscript (the adventurous tale of a group of scientists trying to solve a historical mystery in Italy in the 60's, including the mouth watering descriptions of restaurants, menus, orders, recipes and wines they enjoy in between the visit of a second-hand bookstore from the 'medievole' in Piedmont and ancient cloisters in Lombardy).

He describes the position of Pietro Vittorio, head of the department, when it comes to make decisions that would affect the institution. I'll allow myself to share and freely translate the text.

"The university knew that our department would never support any initiative that was not best for the 'impersonal purposes of the institution' as Vittorio would say. That included relieving us from any decision-making positions. We didn't care: we would even have some compassion for those who fought for leadership positions: "When the pursuit of power is more important than the pursuit of knowledge, universities die". So taught Vittorio.

(...)

As a director, Vittorio proclaimed to the four winds that the transmission of knowledge, the training of students, was the ultimate purpose of the University. He said this was something extremely serious and, therefore, should not be subject to the students themselves, who, after graduation, do not have to answer for the consequences of the 'revolutions' they proposed. He thought that students need to distinguish between the power to challenge and the intellectual authority of their masters. The right to challenge the university is acquired by fulfilling their own role in it. In the case of students, the social duty to take their studies seriously.

Moreover, he would say that the University had no powers to be disputed: it had, instead, commitments to be shared. And the largest, the ultimate one, was with reason, with rationality. That university positions were social or institutional duties, and not positions of power. For him, the ambition for such positions as executive roles was the hallmark of those who would be happier outside the university. The more skilled in the game of power, the more mediocre in the knowledge. (and thus, one can conclude that mediocre were not rare.)

(...)

Once, he explained his colleague and friend Alberto, how he understood his role as director of the Department.

— A director must be a boss. Someone who takes decisions and who are personally responsible for them. He almost spelled p-e-r-s-o-n-a-l-l-y.

— And the professors?

— Each of them can make the decisions they want, provided that they answer personally for each one. We are all responsible adults, aren't we?

— But the council is a deliberative body ...

— ... that may remove me from the direction at any time. But it is me who personally sign the decisions and personally assume the burden of answering for them, in the first person. So it is only fair that I have the power to decide. It is easy to anonymously decide in a group and then delegate responsibility for implementation to the person of the director.

The conversation was quiet and polite. Vittorio and Alberto were friends above all. So Alberto could be frank:

— But a democratic decision must be majority ...

— That is where you are mistaken, my dear: the majority can represent the intolerance, even arrogance. Or do you think that bad faith, when multiplied, becomes purity?

— I think a decision must be debated ...

— And I've never stopped you from discussing my projects. I've never decided anything without discussing with all of you. Convince me that the projects are wrong or inconvenient and I will change or abandon them. The discussion should rationally seek the truth, as would Abelardus say, not only serve as an excuse for the oppression of the majority. Being democratic does mean to bow to the number of votes. It is to honestly submit their own ideas for the consideration of others and learn to surrender to a compelling argument. And that may be the minority one, or a personal one even, why not?!

Alberto rubbed his chin:

— What happens when the majority opinion is the right one? The most convincing ...?

— In this case, it doesn't even need to majority, Alberto. Between a minority who thinks right and a majority who thinks wrong, I prefer follow the minority.

— But how to know what it is to think right?

— Surely the truth is not, necessarily, what a given majority think. Power can be decided by vote; righteousness, not.

— And then?

— What is right, in the case of our Department, or the Institute, for example, is what, at a given moment, is morally acceptable, brings benefit to the group and contributes to the impersonal purposes of the institution. To whomever is accountable, is due the decision. Debate serves to correct possible distortions of the personal criteria of who should decide. In this case, me.

— Isn't that authoritative?

— It would, if the power to decide wasn't delegated. The Council may withdraw the delegation at any time. The Council is all mighty as it can delegate or withdrawn the power delegation according to the will of the majority.

— So now the majority counts? How come?

— Obviously, Alberto. In this case the question is not the right or wrongness of a decision. It is the power of delegating power. It is a matter of strength. It is the exercise of power. The decision may even be wrong: righteousness is not decided by vote. Majority is an expression of force, strength, Alberto. And the strength, rarely is accompanied by rationality.

— In a democracy the right to express an opinion should be unrestricted. Alberto said, crossing his arms. It was his way to express his decision and bring the discussion to the end.

— Then let patients at the Policlinico or prisoners of San Vittore decide how the hospital or the prison should be conducted. Or, students, temporary beneficiaries of the University and do not respond for the effects of such decisions after graduation, to decide on the bylaws or on how teaching and research should be conducted. Students, patients and prisoners are always the majority in these different institutions, as you know my dear.

— I said the 'right' to opinion, Professor.

— For the right's sake? Or to decide?

I do not know how the conversation ended, but that is how it worked in the Department. And it must be said: Pietro Vittorio had been elected for the fourth time to the Board. Unanimously! Styles aside, we all trusted him and his dedication to the impersonal purposes of the institution. And his strict sense of justice."

I have nothing else to add.