Relative Realities? Pt 3: Asking the Real Questions

Why on earth are we still here? Miraculous doesn't even begin to cover it.

As we discussed last time, under the materialist proposition, we had more than enough justification blow this entire planet to smithereens. According to this model, humans are nothing but objects, aren’t they? So what difference would it make in ten billion years if we vanished? And to whom?

The answer it seems, is that for all our tough talk, we don’t really believe this. The rational conclusion of true belief in the materialistic, ‘meaningless’ paradigm of life is nihilism. (consult the Columbine journals, and indeed the writings and biographies of many mass murderers for evidence of that) The reason being that life is inherently chock full of suffering, so, to tally onto that the idea that our strife has no real cosmic significance or value, and in fact, nothing about human life really matters, is the straw that breaks the camel's back. Or rather, the anvil. A nihilistic society couldn't bear the weight of its own existence, especially in the presence of an easy-out button like nukes.

But we aren’t all nihilists. In fact, despite evidence to the contrary, we still intuitively feel the experiential model to be the most suitable, and it shows in how we live. We value our own lives, and the lives of those we care for, and furthermore, life itself, immeasurably, despite an apparent lack of empirical evidence to bolster this attitude.

Here’s a challenge.

Check in with any moral relativist, scientific reductionalist, or deterministic thinker you know, often they’re the same people, (and perhaps you’re one of them) and you’ll find that they have their own code of ethics and won’t take kindly to you violating them. You’ll soon discover that even if they say, or even think that the universe is material and predetermined, they still treat themselves and everyone else as though they have potential, morality, and free will, and as such, ascribe responsibility to themselves and others for their actions, ethical or not. You’ll also find that they still very much care whether they exist or not, erring strongly on the side of the former, and that they would decidedly prefer themselves and those they favor not to suffer any more than absolutely necessary. Finally, you’ll discover that they, just like everyone else, pursue novelty, satisfaction, love and joy, in whatever forms they find it, regardless of whether its 'reasonable' to do so.

Ultimately, whether a person is intellectually convinced is rather secondary. The fact remains that people, religious or otherwise, still act as though they have souls. They still act like they believe in free will, and that their lives matter in some profound, ineffable, potentially cosmic way, and even extend that perception to others, particularly those they love.

In fact, it seems that the more a society or community of any size extends that intrinsic value to every individual, the more prosperous, peaceful, and unified it becomes. Whereas collectives that don’t celebrate the innate, and perhaps divine sovereignty of the individual (any totalitarian state) quickly shatter. Truly, there is no such thing as a functioning secular society, or perhaps even secular individual, especially in the West.

So why don’t we realize this?

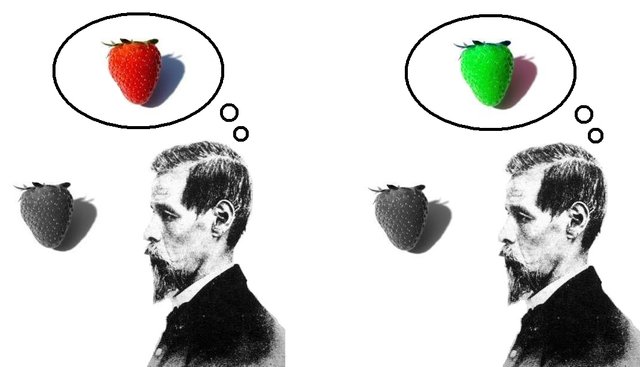

Part of the reason it isn’t fashionable to admit that one’s fundamental axioms about life are quasi-religious is because we often aren’t aware of them. Moralistic presuppositions like to hide in the background of our perceptions, guiding our thoughts and actions from the shadows like Jungian archetypes.

It’s important to reiterate here; morality is a consequence of certain metaphysical intuitions, mainly codified in but not exclusive to religious narratives. Chief among these intuitions is the idea that as a conscious being, one should be oriented towards the greatest good (occasionally called heaven) and away from the worst suffering (called hell). This, and any moralistic propositions should be clearly defined as subjective intuitions, and not fact.

There is NO such thing as objective morality.

The very statement contradicts itself, as goodness can never be derived from, or identified as, an objective fact (obviously).

This plants at least three core aspects of existence, in so far as we’re concerned, firmly on the side of subjectivity, namely; space, time and morality. This number however, could even potentially jump to four or five, depending on whether or not you want to parse motion and space into separate categories, -and there may be real reasons for doing so- and whether or not you consider the double slit experiment and other variants like it to be sufficient evidence that waves can collapse into particle behavior when observed. But I’ll leave the last two up to you.

Nonetheless, another, possibly larger factor scaring people away from an intelligent model of existence is that theology has often been ridiculed by intellectuals, and faux intellectuals alike, mainly for its logical inconsistencies.

Religion’s inability to produce an intellectually coherent model of an intelligent universe makes many individuals fearful to pursue such a thesis, (at least consciously). But our mechanistic alternative isn’t exactly on solid ground either.

This leaves things very much open for interpretation, as far as I’m concerned. The verdict isn’t out just yet. Therefore, while said verdict is in deliberation, and perhaps as a contribution to it, it might be novel to produce a new paradigm which reconciles and potentially supersedes the previous two, partly in curiosity, but mostly for fun.

So, half of this series will be dedicated to reconstituting a living model of the universe minus the dogma and mysticism to observe the effects of such a paradigm. To accomplish this, we’ll use science as a partial foundation for an experiential reality, filtering out the erroneous or unnecessary bits of the previous living model, and building upon what science has already accomplished.

The goal of this work, aside from its enjoyment, is to create a bridge between our reasoning (expressed in the material model) and our intuition (expressed in the experiential model) and heal the apparent disparity between the way we think and the way we live. With said divide repaired, we can integrate these altered intuitions into our perceptions and actions.

So where to begin?

I suppose at the beginning.

To integrate these two basic models, we must first understand them, extract their differences and similarities, and most importantly, note and correct their flaws.

The best way to approach this problem is to insert ourselves into it, for example, to ask ourselves; what would it mean to exist in an intelligent, living universe? And what would it mean to exist in a mechanical, ‘dead’ one?

We’ll start with a rough outline of the reasoning that generated both paradigms.

The Living model:

There’s strong evidence to suggest that our first models of reality emerged through mankind observing the adaptive fitness of certain perceptions, behaviors and attitudes across vast spans of time. This is a very pragmatic, evolutionary approach to understanding life, implying that if we adopt a certain mode of interpreting or acting in the world, and it produces the desired effect, (and we don’t die) then we can assume our apprehension “true”. At least true enough so that we can live, and perhaps even happily.

An example of this kind of truth can be found in the phrase, “all guns are loaded”.

Anyone who’s taken a course on gun safety has this attitude drilled into them, and for good reason. While it’s certainly not literally true, the consequences of adopting this belief are far better for us than not doing so, or worse yet, assuming the opposite.

Truth then, according to our ancestors, is that which promotes well-being, or as Nietzsche once put it “Truth serves life”. (The man had a way of packing troves of wisdom into short, memorable phrases) So, what about the intelligent, subjective model of Being made it so adaptive that mankind once accepted it as truth?

Consider first the traditional Judeo-Christian narrative, and how it overlaps metaphorically with the human condition. Adam and Eve, the original humans, existed in a paradise called the Garden of Eden. The Garden is representative of the perfect harmony between order and nature; a place of flora, but one surrounded by walls, where nature could thrive, but under the watchful eye of a higher intelligence, a utopia.

Ignorant, naked and blind, our ancestors dwelt in the garden without a care. Then, tempted by the Serpent, a universal symbol of the dangers that lurk in any paradise, Adam and Eve ate fruit from a tree of knowledge, convinced that doing so would make them divine, and they soon gained insight into the harsh vicissitudes of life. This act was called the Original Sin, though the reasons for this are obscure.

Why would gaining knowledge be considered wrong, especially if that knowledge would bring us closer to the divine?

First, it’s important to note that the word sin, though it’s commonly thought of as some horrible transgression or crime, is derived from the Greek archery term, hamartia, which literally means to err, or miss the mark. Thus, while it wasn’t evil of mankind to acquire certain knowledge, it was still considered a mistake.

However, some major questions about these few passages have yet to be addressed. For example, why is it the Serpent that tempts Adam and Eve to eat the forbidden fruit? Why is it a sin for humans to acquire divine knowledge? And what about this knowledge was so powerful that it was considered divine?

Next time we'll cover more on the knowledge of Good and Evil, Serpents, death and much more.