The Amateur Mycologist #29 - Lycogala epidendrum - My First Slime Mold! - Now With Corrective Edits Regarding The Life Cycle of Slime Molds

These posts are not for foraging. They are intended for entertainment and intellectual satisfaction only. These posts are not a field guide nor comprehensive in any way - their accuracy is not assured in any way. Do not eat wild mushrooms unless you are a professional, have substantial professional assistance or have a wealth of personal experience with a specific species. Do not make any foraging decisions based on these posts. To do so could be dangerous or life threatening.

This one post does mention toxicity in order to illustrate the importance of being 100% certain in your ID before eating a wild mushroom. Cutting corners can be immensely dangerous.

It's been pointed out to me there may be errors in my representation of a few details about slime mold life cycles and this species nutritional habits. I have tried to fix these issues. My thanks to /r/mycology user najjex for pointing out the errors - I believe (and hope) that they have been rectified.

This is Lycogala epidendrum

I put this first because its a more interesting photo.

But this is how I found a specimen in a much older stage.

These little black puffballs presented a real conundrum. What in the world are they?

I found them on a big downed log – the same one on which I found the giant colony of Hypholoma sublateritium – just sitting there all by their lonesome in the middle of a rotting piece of bark. Three of the tiniest little puffballs you ever done seen.

They had a nearly black skin with an almost scaly appearance in the hand lends.

Plus they were really quite small.

Really very tiny – the largest was not barely 1cm across.

And the smaller two were not even half of that.

I needed to take a look inside.

Purple spore mass.

This picture cuts out the purple a little, but it really was a dull purple through and through. And apparently fairly mature and ready to burst. But no dispersal hole in the top… and they were still quite firm to the touch.

I wondered if maybe a look at the spores under the scope would shed some light somehow

It did not – although the spores were very different than others I’ve seen so far.

They were spherical and quite even in their measurements, as well as possibly textured, although with my microscope that is difficult if not impossible to tell for sure. Although a pleasure to look at, they did not clear up my confusion.

I officially had no idea what in the world was going on. These things were puffballs, but they did not meet the parameters of any species of puffball I’d ever seen or heard of. Most puffballs are much larger in size, sometimes, like some Calvatia species, simply gigantic. Plus, even the earthballs that have purple spores don’t have such uniformly black skins.

I did some googling – a lot of googling – and a bunch of reading as well, out of good old fashions books. This led me precisely nowhere. The best I could come up with a genus of black or blackish puffballs sometimes called “Cramp balls”, or Carbon balls – the genus Daldinia.

Daldinia concentrica is basically the representative species. But, although it is black, the damn things are way too big. Plus their interiors are not purple, and they are well known for the way hat the spore mass inside arranges itself in concentric layers – hence the species name.

(SIDE)

So, without a clue as to what I was looking at, I decided to go to my fall back resource – the New York Mycological Society.

Now, to be clear, these people are more knowledgeable – both individually and, of course, collectively – than I will ever be. However, I try to save them as a last resort for specimens that really defy expectations and prove particularly difficult to identify. This was definitely one of those situations.

So, I posted my analysis, gave my thoughts so far, and waited for about 2 minutes before the man himself, Gary Lincoff, responds unequivocally with Lycogala epidendrum.

Well, that was simple enough. Gary Lincoff is famous in the mycological world – the guy literally wrote the Audobon field guide for North America. So, when he speaks with assuredness, it’s best to listen

First thing I do is google L.epidendrum, only to have my head explode.

WHAT?!

No, Gary has not lost his mind. These are the same species as the black puffball like thing I found and pictured above. I was blinded in my search by my presuppositions and past experience with traditional fungal puffballs, and never considered the alternative.

It turns out that Lycogala epidendrum is not a fungus at all. It is a slime mold.

Slime molds used to be taxonomically bundled in with fungi, but were eventually separated from the pack and given their own taxonomic lineage. Although they may appear mushroom like sometimes, they are fundamentally different in awesome ways.

You’ll remember that a mushroom is just the reproductive arm of a larger fungal organism known as the mycelium. The mycelium is a spiderweb like series of filaments that grows as one living mass usually underground and from which spring forth the mushrooms we see when the time comes to reproduce.

Slime molds are something else entirely

This colony of L. epidendrum at different levels of maturity is not what it seems.

Slime molds are sort of insane. Unlike mycelium, slime molds start their life cycle as individual, self-reliant, often single, but large celled globs.These individually living and reactive globs of slime – called plasmodia – spend the first portion of their life living individually.

These individually living and reactive globs of slime – called plasmodia – spend the first portion of their life living individually. They swarm over things, slowly engulfing them like the big white bubble in The Prisoner, or giant, visible to the eye Amoebas.

But, eventually, when the time is right, the cells release a chemical agent which informs all the cells to begin working together and, all at once, they join forces and transform into the final slime mold’s fertile structure. In the case of L.epidendrum, this takes the form of a puffball like sphere with a skin, or peridium, holding in a large quantity of spores.

I don’t think I did a good enough job explaining how unbelievable that is.

AGREED - Let's try that again with a new source or two- keeping things admittedly broad strokes. In general slime molds do start life as small, sometimes single celled organisms. Those spores above in the mature L.epidendrum will disperse, land on the appropriate growing medium, and germinate into the initial, often amoeba-like cells of the pre-macroscopically visible slime mold.

Now, L.epidendrum, as I understand it, is a Plasmodial slime mold. Which means that, at some point, those single celled amoeba-like organisms join together, and mass up, in a big mass of slime called a plasmodium. This is where I got particularly confused before. The plasmodium is not, by the standards of many biologists, a single celled organism. It is a congolomeration of many cell nuclei held together in a "plasma-membrane", but not delineated by conventional cell walls. If you consider the structure of an onion, for example, under a microscope, it is has well defined cells delineated from each by fairly rigid cell walls. Plasmodium is a collection of the interiors of cells without the walls to divide them one from another.

This final product I found was not spawned from one wholistic organism.

Rather it is the collaborative effort of a bunch of independent, individual and separate organisms which evolved to spontaneously morph into something totally different.

Let's keep going with the clearer explanation. The plasmodium needs to eat, and it does so by slowly crawling along surfaces and encompassing stray organic material and absorbing it, and its nutrients, directly into itself. In that sense, the plasmodium is a little like the white bubble from the prisoner, albeit that is an oversimplified metaphor. However this method of "eating" is called phagocytosis and I think it's what the giant white bubble was trying to accomplish.

Inside of the plasmodium, there are actually structures - for example veins or vessel that carry cytoplasm to and fro within the plasmodium and which help enable the whole mass to move around. The plasmodium crawls around for awhile, absorbing nutrients directly from encompassed organic material, until it - they? - is/are ready to begin the transformation into their final form - in the case of L.epidendrum, the puffball like structure pictured herein. Not all plasmodium transform into this particular spore-bearing structure - but they do all eventually make some kind of transformation which allows them to disperse spores.

The spore-bearing mass that the plasmodium transforms into is called an aethelium and it is the final form of the slime mold before the release of the spores and the renewal of the life cycle at the single cell stage when the spores disperse and, hopefully, germinate.

There is a ton more to say and learn about plasmodial slime molds alone, let alone the other varieties of slime mold which exist. I'm not going to go into any more detail at this point, but for more info you can check out the sources I cited to above, or go ahead and purchasse "The Social Amoebae" by John Tyler Bonner. I'm considering it myself - although I think instead I will buy "Myxomycetes: A Handbook of Slime Molds"

Slime molds have existed for millions of years, yet there is almost no fossil record of their existence. As the linked to page from Berkeley explains, the molds just don’t leave behind anything substantial enough to be preserved through geologic timetables.

Nonetheless, slime molds like Lycogala epidendrum have thrived on our planet for far longer than human beings have been alive and they continue to thrive despite their bizarre nature.

MUSHROOM SLIME MOLD CHARACTERISTICS

- Fruiting Body – The slime mold starts as amoeba like single cells, coalesces into a multi-nucleic mass known as a plasmodium, and then eventually, after consuming enough and when conditions are otherwise right, the plasmodium finds a good spot and morphs into an aethelium, or the spore bearing mass. This mass is at first light in color - pink to white -Eventually a skin forms around a central mass. This eventually darkens and matures – the skin taking on a lighter look, losing the pink, eventually turning almost black and bearing a pattern similar to some puffballs, but not much more than a cm in diameter. Inside of the skin, a similar maturation is occurring as a pink slime matures into millions and millions of purple spores capable of reproducing.

- Flesh = N/A

- Stem ("stipe") = N/A – In fact – it’s worth remembering that the slime mold does not grow from a singular organism like a fungi’s mycelium. There is no mycelium inside of the piece of wood these molds grow on. The slime mold cells can at first live on their own, and then later the plasmodium functions as a unit to move around, find and digest food, and eventually develop into an aethelium.

- Spore Print = Purple spores

- Ecology ("How it grows.") = They are saprobic and eat dead wood from Summer through late fall. I found mine fully mature on a cold November day. See the explanation above or the several sources for more detail.

- Distribution = Apparently all around North America

- KOH reactivity = Did not test

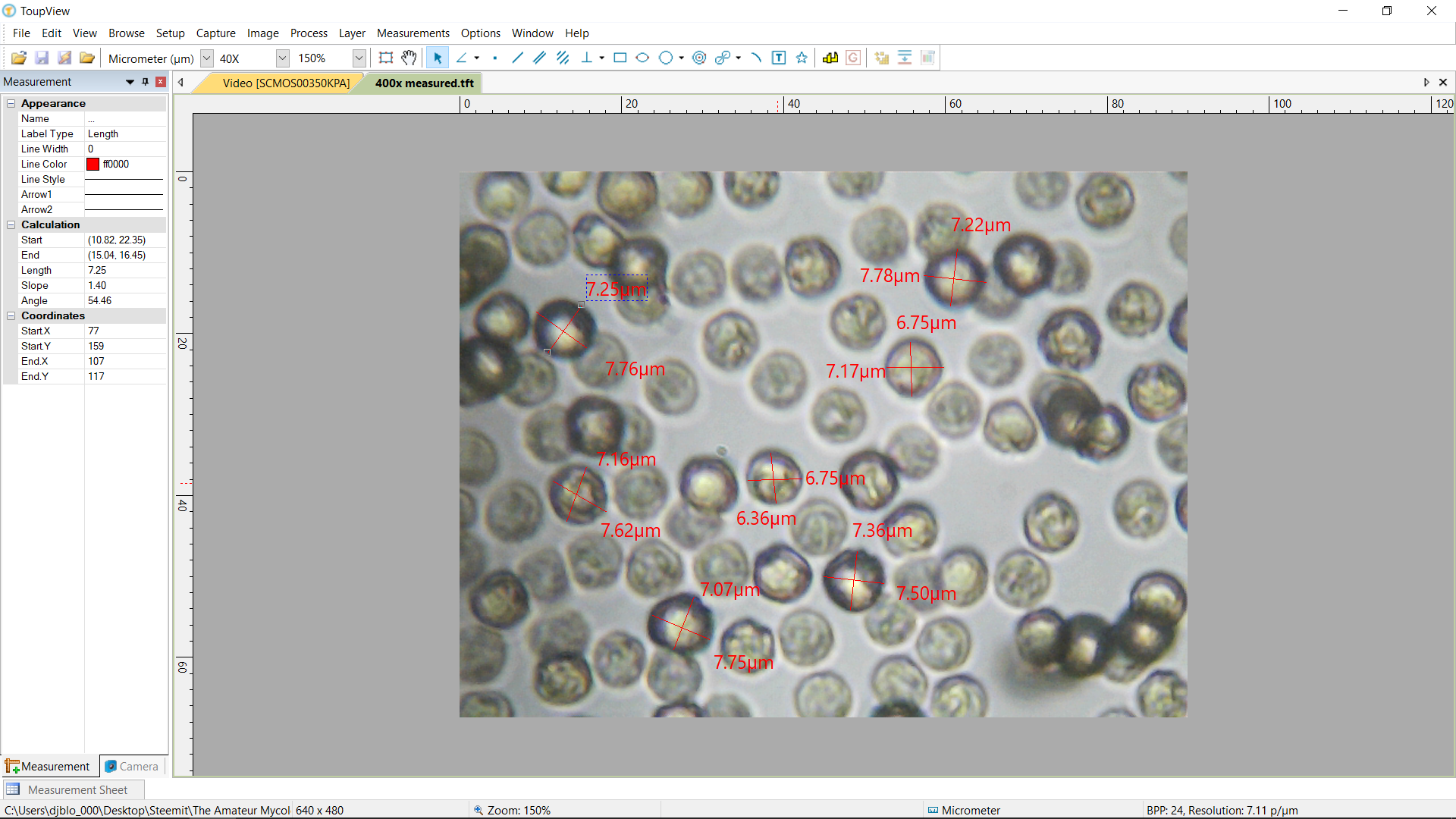

- Microscopic Traits = Spores were spherical or globose, and all uniformly within a diameter range of 6-8microns.

THIS POST IS NOT INTENDED FOR FORAGING PURPOSES AND TO USE IT FOR THOSE PURPOSES WOULD BE DANGEROUS. DO NOT HUNT WILD MUSHROOMS WITHOUT RELYING ON A COMBINATION OF PROFESSIONAL FIELD GUIDES, IN PERSON PROFESSIONAL GUIDANCE, OR IN PERSON GUIDANCE BY SOMEONE TRUSTWORTHY WHO HAS COPIOUS LOCAL, SPECIALIZED MUSHROOM HUNTING EXPERIENCE. FAILURE TO DO SO CAN RESULT IN GRIEVOUS PERSONAL HARM OR DEATH.

Photos Are My Own Except

[5]J Milbum, Own Work, Daldinia concentrica, CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

[6]picture taken by Olaf Leillinger on 1998-05-13, CC-BY-SA-2.0/DE and GNU FDL, via Wikimedia Commons

[7]Benny Mazur from Toledo, OH, CC-BY-SA-2.0, via Wikimedia commons

Microscopic photos were taken using an AMScope M150B entry level microscope. If you use microscopes, I'm quite sure you've never heard of this model - but its cheap and available on Amazon. The camera lens is also AMScope, MD35 - by far their crappiest microscope camera. But, still capable of material, relevant, and in some cases, dispositive, data collection. Lastly it should be noted that the precise magnifications are not easily deduced using the camera - but based on relative spore sizes compared to known microscopic photos from Kuo and other sources, I estimate 40, 100 and 400x.

Information Sources

[1]Kuo, M. (2003, August). Myxomycetes: The slime molds. Retrieved from the MushroomExpert.Com

[2]Introduction to the "Slime Molds", Berkeley

[3]Urban Mushrooms on L.epidendrum

[4]Tom Volk very briefly on L.epidendrum

[5]Messiah College on L.epidendrum

Nice post @dber, I didn't know anything about slime mould, but I am very impressed with how they operate now. That's very cool how they start out as individual's and then all come together in the end as one. You did quite well in describing how unbelievable that is. Definitely a great learning day for me, thanks for that.

I appreciate how consistently you read, and thoughtfully you comment, on my posts!

The strange life of slime molds would almost be inspiring, if they were so alien looking.

I have always found mushrooms and mycellium fascinating, I'm so busy day to day with my family so it's really nice to be able to follow you and get involved in your wonderful discovers and learn more. I've alot of respect for the amount of work you put into your posts. Thanks so much for your appreciation x

I didn't see in before, so attractive that @dber

Quite beautiful and totally bizarre

Oh, really i got a new experience from here, ever taking to remember @dber

I remember picking up little puffballs in my back yard as a kid. I would open them and a puff of what looked like smoke (spores) came out. I was so fascinated by it. Thanks for the post @dber!

These look very similar to a puffball - and yet are the farthest thing from one at the same time. That's why it confused me at first too#

My husband and I live in northeast Kansas out in the "boonies." A few summers ago, a neighbor decided to eat a mushroom out in her yard. She had to go to the emergency room that day due to severe diarrhea. She lived but we were amazed that someone would do that on a whim.

I wish i was also surprised :/ - DONT EAT RANDOM MUSHROOMS FOLKS!

This looks almost exactly like those little things from which the spores came and infected that first guy in the last Alien movie.

Thanks for these awesome posts man! 🍄

Haha - they also remind me of Invasion of the body snatchers, especially in their protoplasmic stage which is not pictured here.

Not sure why anyone would use this for foraging purposes. I guess you still have to do your job and warn people. Kind of like a disclaimer thing.

Folks will use almost anything to legitimize their decision to eat some random thing they find. You'd be amazed.

You're right. It wouldn't surprise me if someone made a post on steemit initiating a law suit or something against you. People these days are getting crazier and crazier.

OMG.... Its nature