Mendel's works, part I (Speculative theories on inheritance and introduction to Mendel's work).

People have always been curious to know why children are similar to parents and grandparents. They have also wondered why a plant that produces small fruits, originates another plant with similar fruits. These questions marked the beginning of knowledge about inheritance and later about genetics, science that was born as a branch of biology, from the first plant crossing experiments carried out by the Augustinian monk Gregor Mendel.

Historical background to Mendel's work.

All the explanations about the mechanisms of the biological inheritance made before Mendel resulted in approximations to the truth, without going beyond being suppositions, since they lacked scientific rigor. However, the previous works kept alive the curiosity to know the mechanisms of the inheritance, and that restlessness led to the elaboration of the true principles of the biological inheritance. Among the theories about the mechanisms of inheritance that came from Mendel's work, we can mention:

- Preformism.

The first defender of this theory was the Italian physician Giuseppe Degli Aromatari (1586-1660). The preformism postulated that in the ovum or sperm was already present and "formed" the fetus as a small man, called "homunculus." This little man was endowed with the different parts of the body, although as their dimensions were very small or were in a liquid state, they were not completely visible.

A) Yes. As the fetus developed, the gradual solidification of each part occurred, and the organism increased in volume. Among the most famous preformists include the physiologist Albrecht von Haller (1708-1777) and the microscopists Charles Bonnet (1720-1793), François de Plantade (1670-1741), Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694), Jan Swammerdam (1637-1680) ) and Anton van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723). With the progress and improvement of the microscopes, it was proved that what looked like a little man in the sperm was the structure of the head, known as acrosome, which contains enzymes that facilitate the process of fertilization.

Source

- Epigenesis.

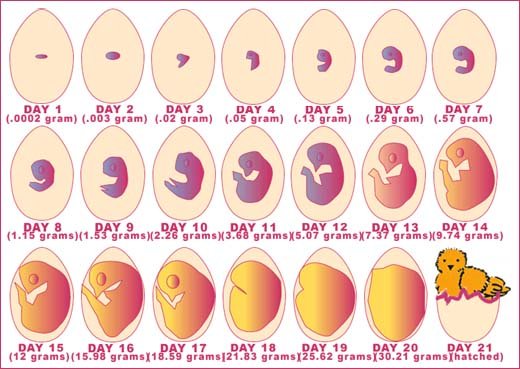

According to this theory, in the ovules and spermatozoa, there is an undefined matter that, after fertilization, must only be differentiated and reordered, which leads to the formation of an embryo and then of a fetus. The main defender of this theory was Karl E. von Baer (1792-1876), first to describe the embryonic development of a chicken, which is why he is known as the father of embryology.

Source

- Pangénesis.

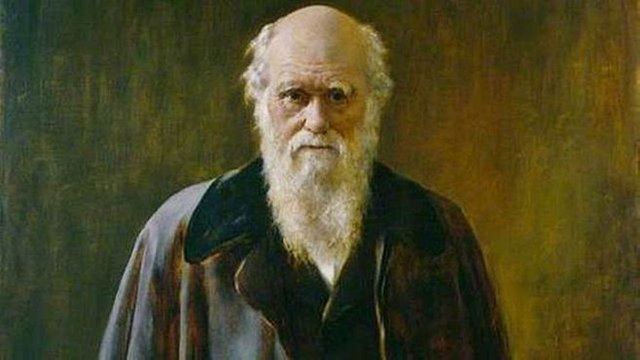

This hypothesis was initially postulated by Aristotle (384-322 BC), and many centuries later by Charles Darwin (1809-1882), as a tool to explain the similarity between parents and children and the process of evolution through the section natural. Darwin was based on a simple speculation, which had no basis in any scientific fact, which is why he called it "tentative hypothesis of pangenesis." According to this hypothesis, each organ and structure of the body produces small particles called pangenes or gemmulas, which via blood reach the sexual cells or gametes. When the male gamete unites with the female gamete and a new organism originates, it contains gemmulas of both parents. This is how Darwin explained the similarity between parents and children. Francis Galton (1822-1911) rejected this hypothesis after several experiments.

Charles Darwin.

Source

- Inheritance of the acquired characters.

This theory was postulated by the French biologist Jean B. Lamarck (1744-1829) and is based on two important facts:

- A muscle that is constantly exercised has a greater development.

- There is a tendency for children to resemble their parents.

From these two facts, it is easy to think that the changes caused by the environment in the organism, that is, the acquired characters, are inherited from parents to children, even if the environment is not the same that caused the change in the parents. .

According to this theory, for example, the neck of the giraffes has been lengthening through the generations, because these animals tried to catch the highest leaves of the trees. This lengthening of the neck (acquired character) was transmitted to subsequent generations. Lamarck's hypothesis was also collapsed experimentally: The tail was cut to laboratory mice, which then mated to observe the offspring. All the offspring obtained had tail. These results showed that the acquired character (cut tail) is not transmitted from generation to generation, that is, that the acquired characters are not inherited.

Source

- Germinal plasma.

This theory was postulated by August Weismann (1834-1914), who questioned Lamarck's theory. Weismann called germ plasm or germplasm to the sex cells or gametes and somatoplasm to the rest of the cells of the body or to the cells of the embryo that originates each system of the organism. The changes that the germplasm undergoes are heritable, while the changes experienced by the somatoplasm are not. According to this postulate, the germplasm is the vehicle that uses the somatoplasm to pass from one generation to another.

August Weismann.

Source

The emergence of genetics.

Genetics today handles concepts related to inheritance, which are due to the contribution of Gregor Mendel's research. However, in the development of the basic principles of inheritance, it has contributed to a large number of scientists who generalized and expanded Mendelian approaches to a large number of organisms.

The scientific work of Mendel.

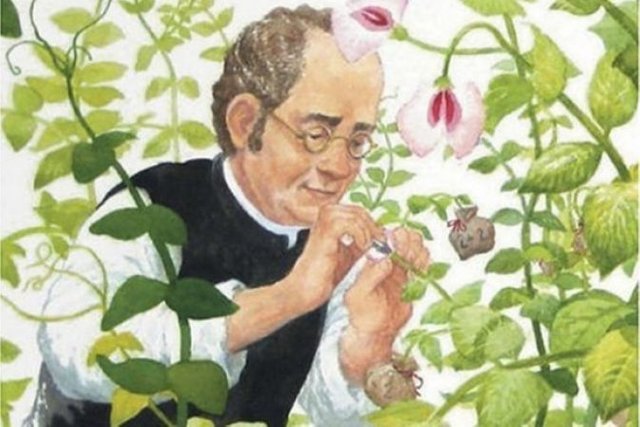

Johann Mendel (1822-1884) was born in the town of Heizendorf, which then belonged to Austria. His parents, farmers, approached him from small to work with crops. In 1843, at the age of 21, he entered the Augustinian monastery of Santo Tomás, in Brno, and took the name of Gregor. In the monastery, a statute existed according to which the monks had to teach sciences in the establishments of higher education of the city. For this reason, most monks studied science and engaged in various scientific activities. Mendel was sent to the University of Vienna where he studied mathematics and natural sciences from 1851 to 1853.

Source

On his return to the monastery, in 1854, he started a series of works on plants. I wanted to know the principles that govern the transmission of characteristics from the parents to their descendants. He studied a great variety of ornamental plants and fruit trees of the monastery, but his most important work for genetics was with the common pea plant (Pisum sativum). Mendel studied in a garden 7 meters wide. It cultivated about 27,000 plants of 34 varieties, examined 12,000 descendants obtained from crosses and observed some 300,000 seeds.

In 1865, Mendel finished his work and presented his results at a meeting of the Brno Natural History Society. However, his conclusions did not arouse curiosity among the limited audience, consisting mainly of astronomers, botanists, and mathematicians. The summary of the conference given by Mendel was published in 1866, in the annals of the Natural History Society of Born. The issues of the magazine were sent to London, Berlin, Vienna and the United States. Two years later, Mendel had to take on his own duties as abbot of the monastery, so he abandoned his investigations. After more than 30 years of presenting the work of Mendel, in 1900, researchers Karl E. Correns (1864-1933) in Germany, Hugo de Vries (1848-1935) in Holanda and Erich von Tschermak-Seysegegg (1871- 1962) in Austria, modeled independently on Mendel's works.

In the crosses carried out by Mendel, a whole symbology was applied to understand the transmission of characteristics from the parents to the descendants, and that laid the foundations for the definition of key concepts in classical genetics.

Mendel's study material was the Pisum sativum plant.

Source

References:

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epigenesis/

- https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/charles-darwins-theory-pangenesis

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3730912/

- https://www.britannica.com/science/germ-plasm-theory

- https://www.storybehindthescience.org/pdf/mendel.pdf