The Anthropological way: Doing fieldwork - Research (Part 3 - Final)

The Anthropological way: Doing fieldwork - Research (Part 3 - Final)

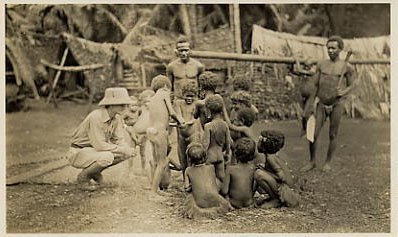

Ethnographic fieldwork - Anthropological Self-Criticism

Are the reports or text that anthropologists produce true reflections or representations of the people and sociocultural systems that they study?

Do they report on what they perceive about peoples' values, lifestyle etc are, or what their values and lifestyle actually are - or at least what these are from their perspective?

Do anthropologists not take their own personal or sociocultural biases and assumptions into the field with them?

Isn't the very presence of an anthropologist (an outsider) in the field disruptive and doesn't it influence the behaviour of the people studied (and therefore distort the data)?

Don't anthropologists go into the field and impose upon people for what they can get out rather than for what they can give back?

Anthropologists have been posing these and many other searching questions about the anthropological endeavour for many years - but this soul - searching and introspection have intensified over the last few years. Concerns were increasely raised about many issues, including the following:

- the power relation between the anthropologist (researcher/subject)and the people studied (object)

- objectivity as opposed to subjectivity

- modes (way/styles) of representing or depicting those studied

- accountability and reciprocity

- relativism and ethnocentrism

- reflexivity

- the emic and the etic

Many of these terms and concepts might at this stage be unfamiliar to you. Let us now see what they entail and imply, and what the critical debate in anthropology is all about.

As long ago as 1922 Malinowski encouraged an approach to fieldwork that, through participant observation, would enable anthropologists to "grasp the natives' point of view"; the belief was that this subjective perspective would complement the researcher/anthropologist's more objective viewpoint ( Malinowski 1961:25 - Argonauts of the Western Pacific). In subsequent years it became increasingly important for anthropologists to see the people being studied as actors "in" their own sociocultural context and to be aware of how they perceive and categorise the world and what has meaning for them. This is known as the emic approach, and is in contrast with an approach that studies the sociocultural system from the "outside" as a scientist. The latter is known as the etic or researcher-oriented approach. Here, the focus of research shifts from people's own categories, explanations and interpretations to those of the anthropologist. In the case of the etic approach, the researcher works from the assumption that people are so subjectively involved in their own lifestyle that they find it difficult to have an impartial view of it. In fact, the researcher, like all scientists, is also human and possesses preferences and predispositions that make unqualified objectivity impossible. This is why anthropologists combine the etic and emic approaches in their fieldwork strategies. Experience has shown that interaction between these two approaches produces a more meaningful and accurate representation of peoples' sociocultural systems.

Related to the emic and etic approaches, and complementary to them, are the notions of cultural relativism and ethnocentrism. These concepts have had currency in anthropology for much longer quite simply because people in general display, or are "guilty of" attitudes that are symptomatic of such perceptions - particularly ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism is the inclination of many people to regard their own sociocultural system or way of life as superior, and they use the values and practices of their own system to judge the behaviour and beliefs of others. Although ethnocentrism enhances sociocultural solidarity and a sense of community among people who share similar traditions, it encourages the belief that people who behave differently are strange, immoral or even barbaric or primitive. People tend to believe that their own familiar explanations, opinions and customs are correct, proper, true and moral.

Counteracting ethnocentrism is the notion of cultural relativism and this suggests that behaviour in a specific sociocultural system should not be judged by the values and norms of another system. In other words, a group or community or society's behaviour, ideas, beliefs and customs should be studied and understood within their own context and judged as equally valid. Anthropologists have tried to negate ethnocentrism by spending extended periods of time in different sociocultural systems among the people themselves - thus learning by direct and personal experience that "different" people are no less human. They have thus resisted ranking sociocultural systems and have attempted to understand them on their own terms. If they assess them, they simply try to judge whether these systems satisfy the needs and expectations of the people themselves.

Cultural relativism, if taken to the extreme, can also, however, be problematic because it would imply that there is no such thing as a universal human morality. If one adopts this view, then one has to accept the practice of female genital mutilation, clitoridectomy (the removal of a girl's clitoris), which is still carried out in some parts of Africa and the Middle East. One would also have to find acceptable the gas chambers for Jews in Nazi Germany during World War II and the mass extermination of people and "ethnic cleansing" that has occurred in several African countries in the last decade. Also, of course, there is the issue of human rights and equal rights for women and minorities (which many countries of the world still deny today).

Ever since the 1970s anthropologists have increasingly contemplated their own role and experiences in the field. They are now often prepared to be introspective and honest about the variables that have an influence on their ethnographic work, not least of which is their own influence on the process and product of fieldwork. They have talked and written about every aspect of their environment, including:

....their relationships with informants, and the contexts in which they gathered their material. While in the past some dismissed these reflections on fieldwork as self-indulgent "navel-gazing", it is now generally accepted that they have made an important contribution to the discipline because we can better understand and evaluate an ethnographic text if we know something about the writer, the experiences upon which the text is based, and the circumstances of its production. Furthermore, these reflections turn anthropologists into better fieldworkers by making them aware of their own practices, emotions, biases, and experiences. (Sluka & Robben 2007:2 - Fieldwork in Cultural Anthropology : An Introduction)

From this ongoing anthropological self-criticism has emerged a number of "trends" or, as they are sometimes called, "turns":

- The awareness of the relationship between power and the construction of knowledge resulted in a concern with reflexivity - the "reflexive trend" - which produced different fieldwork relationships and new styles of ethnographic writing.

- Most anthropologists rejected the postmodern critique that fieldwork is inherently a form of imperialism, oppression and control, but this critique did encourage them to be more reflexive and they did reassess their relationship with the people they studied. This led to what became known as the compassionate turn - a moral awareness and a willingness to take up the cause of the people being studied and "... our ability to listen, and to observe carefully and with empathy and compassion" (Scheper-Huges 1995:415-418 - The primacy of the ethical: propositions for a militant anthropology). This led anthropologists to increasingly study violence, genocide, suffering, trauma, poverty and oppression.

- The "ethnographic encounter" also came into sharper focus - that is, the way in which fieldwork is conducted and how research participants/"informants" are drawn into the process and incorporated into the ethnographic report. Multivocality thus came to the fore, that is, more than one "voice" was to be heard, both that of the anthropologist and those being studied.

- Contemporary ethnographers have tried to ensure that the voice of the "other" is heard more clearly. And this they have done through more active involvement of research participants in the co-production of ethnographic accounts, narratives, or texts. This is done by extensive direct quotations, co-authorship, and collaboration with research participants. As Tedlock has observed, beginning in the 1970s, "there was a shift in emphasis from participant observation to the observation of participation" (Journal of Anthropological Research 1991:78), entailing "a representation transformation" in which both the fieldworker and "other" are "presented together within a single narrative ethnography, focused on the character and process of the ethnographic dialogue". Narrative ethnography became a creative intermingling of lived experiences, field data, methodological reflections, and cultural analysis by a situated and self-conscious narrator. Tedlock argues that the development of this new "narrative ethnography" is driven by a new breed of ethnographer, who is seriously interested in the co-production of ethnographic knowledge, created and represented in the only way it can be within an interactive self/other.

The British anthropologist, Adam Kuper, however sounds a warning that narrative ethnography can be exaggerated so that eventually the anthropologist is nothing more than a medium or spokesperson for people who criticise existing social and political order - there is no editorial input in the interpretation and writing of his/her fieldwork data. Kuper's criticism should be taken to heart, because the anthropologist, both as an objective observer and the one who records and verifies the data, is responsible for the final product of his or her research after it has been presented to the people concerned for their approval.

Finally, the matter of reciprocity. Another development in what has come to be called the "new ethnography" is the increased commitment to reciprocity and collaborative research - to giving something back to the research participants for their collaboration - as an ethical requirement of fieldwork.

End of Part 3 - Final

Images are linked to their sources in their description and references are stated within the text.

Thank you for reading

Thank you @foundation for this amazing SteemSTEM gif

Pretty... But this science has to change because it has featured many online communities such as Facebook, Twitter, and Stimeet.

The relationship that gathers people is ideas, not geography, language, or religion.

I am not sure exactly what you mean:)

But thank you for the comment.

excellent post, greetings and I'll follow you

Thank You!

excellent post I love, greetings I follow you when you want to go through my profile. Thank you.