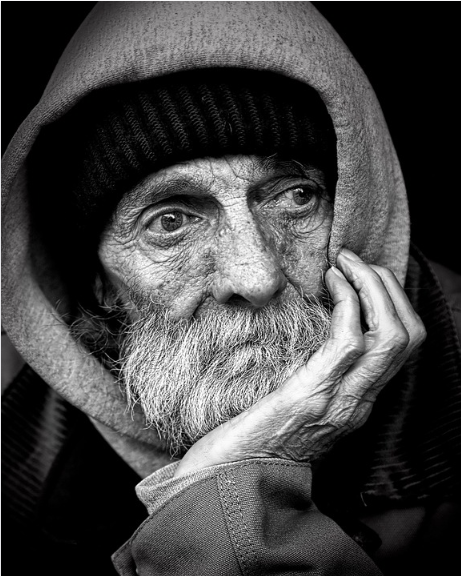

POVERTY: A MAN TROUBLE HEART

“

You got a choice to make, man. You could go straight on to heaven. Or you could turn right, into that.”

Brothers, what is the most fashionable word these days, eh? These days the most fashionable word around is, of course, “electrification”.

I don’t deny the vast importance of shining a light on Soviet Russia. But it does have its not-so-bright side. I’m not saying, Comrades, that it costs too much. It doesn’t cost too much. No more than the cost of money. That’s not what I’m talking about.

What I’m talking about is this:

I lived, Comrades, in a great big house. The whole house ran on kerosene. One person had a smoking wick in a jar of oil, somebody else—a little lamp, while somebody else had nothing but the light of a prayer candle. Downright poverty!

But then they began installing electricity.

The first to hook it up was the authorised representative.

A quiet man, he didn’t let on about much. But he was acting strange all the same and kept on thoughtfully blowing his nose.

But still, he didn’t let on about much.

And now our dear landlady Elizaveta Ignatyevna Prokhorova came along and suggested we light up our own flat.

Everyone, she said, is doing it. The authorised representative himself, she said, has done it.

Well, then! We went and installed electricity for ourselves.

We installed it, turned on the light, and—Holy Moses!—there’s dirt and decay everywhere.

It used to be you went out in the morning, came back in the evening, had yourself some tea and went to bed. And by the light of the kerosene you saw none of it. But now we’d switch on the electric light, take a look around, and here’s somebody’s holey shoe lying about, here the upholstery is ripped and a bit of it is sticking out, here’s a bedbug trotting away—saving itself from the light, here’s a rag from who knows what, here a pool of spittle, here a cigarette end, here a flea hopping along…

Holy Moses! It’s enough to make you shout for help. Just looking at such a spectacle is heartbreaking.

The settee, for example, that we had in our room. I thought the settee was just fine—it was a nice settee. I often sat on it in the evenings. But now I’d switch on the electric light and—well I never! Would you look at that settee! It’s all sticking out, it’s all sagging, all its stuffing’s coming out. I can’t sit on a settee like that—the soul won’t have it.

Well, I think, the good life this is not. It’s nasty just looking at all this. Nothing I do seems to go right any more.

My Parents and My Children

I see the landlady Elizaveta Ignatyevna is looking sad too, puttering away in the kitchen, tidying up.

“What,” I asked, “is bothering you, missus?”

And she waved her arm.

“I,” she said, “am a nice person, and I didn’t know I was living in such poverty.”

I look at the landlady’s stuff—indeed, I think, it’s not first-rate: dirt and decay and assorted rags. And all so brightly lit up you can’t help seeing it.

Coming home began to lose its shine.

I’d come home, switch on the light, admire the lightbulb, then hit the sack.

Then I had a think. I got my pay on payday, bought some calcium, dissolved it in some water and set to work. I stripped the upholstery, beat out the bedbugs, swept away the cobwebs, got rid of the settee and painted—I clobbered the place. The soul sang and rejoiced.

But even though it turned out well, it was all for nothing. In vain and to no end, brothers, did I blow my money—because the landlady went and cut off the electricity.

“It hurt,” she said. “Everything looks so wretched in the light. What,” she said, “should I shine a light on such poverty for? It only makes the bedbugs laugh.”

Oh I begged and I reasoned, but it did no good.

“You can move,” she said, “somewhere else. I don’t want,” she said, “to live with the light. I don’t have the money to redecorate the decorating.”

Do you think it’s easy, Comrades, to move when you’ve blown a pile of money on decorating? And so I just gave in.

Eh, brothers—electric light is good, it’s just no good to live with.

The Galosh

Of course, it’s not hard losing a galosh on the tram.

Especially when everyone’s bearing down on you from the side and some delinquent’s stepping on your heel—and there you go, no more galosh.

Losing a galosh—there’s nothing to it.

They had my galosh off me in no time flat. You could say I didn’t even have the chance to cry out.

When I got on the tram, both galoshes were in their place. But when I got off the tram, I looked down and one galosh was there on my leg, the other one wasn’t. My boot was there. My sock, I saw, was there. And my underpants were in place. But the galosh was gone.

And you don’t, of course, go running after the tram.

I took off the remaining galosh, wrapped it in newspaper and went on my way like that.

After work, I thought, I’ll go and find it. I won’t let the merchandise disappear! I’ll dig it up somewhere. After work I went looking. First things first I got some advice from a tram driver I know.

He gave me cause for hope right off the bat. “Be thankful,” he said, “you lost it on the tram. If you lost it somewhere else I couldn’t guarantee you, but to lose it on the tram—that’s the holy of holies.

We’ve a bureau for lost things. Come and get it. The holy of holies.”

“Well,” I said, “thanks. That’s a real load off my mind. The thing is the galosh is practically new.

I’ve only been wearing it three years.”

I went to the bureau the next day. “Brothers,” I said, “can I please have my galosh back?

They got it off me on the tram.”

“You can,” they said. “What kind of galosh is it?” “It’s a galosh,” I said, “an ordinary galosh. Size twelve.”

“We have,” they said, “maybe twelve thousand size twelves.

What does it look like?”

“It looks like an ordinary galosh: the back is beat up, of course, and there’s no lining, the lining wore away.”

“We have,” they said, “more than a thousand galoshes like that.

Does it have any distinguishing characteristics?”

“Yes it does,” I said, “have distinguishing characteristics. The toe cap is more or less detached, it’s scarcely hanging on.

And the heel,” I said, “is almost gone. It wore away, the heel did. But the sides,” I said, “are still all right—for now they’re there.” “Have a seat,” they said, “here.

We’ll go have a look.” And all of a sudden they brought out my galosh. I mean, I was awfully pleased. Right touched.

See how great, I thought, the system works. And what, I thought, dedicated people, the lengths they went to for the sake of one galosh.

I said to them, “Thanks.” I said, “Friends, I’ll be grateful to you till the day I die. Now give it here and I’ll put it on.

Thank you very much.” “No,” they said. “With all due respect, Comrade, we can’t give it to you. We,” they said, “don’t know—maybe you aren’t the person who lost it.” “Yes,” I said. “It’s me who lost it.

You can give it to me, I swear.” They said, “We believe you and we sympathise with you, and most likely you are the one who lost this particular galosh. But we can’t give it to you.

Bring us a certificate that you have actually lost a galosh.

Have this fact notarised by your house management committee, and then without any undue red tape we’ll give you what you’ve lawfully lost.”

I said, “Brothers!” I said. “Blessed Comrades, they don’t even know this fact at the house. Maybe they won’t give me a document like that.”

They answered, “They’ll give it to you.”

They said, “It’s their job to give it to you. What else are they there for?” I took one last look at the galosh and left.

The next day I went to our house’s chairman and said to him: “Give me a document.

My galosh is lost.” “But did you really,” he said, “lose it? Or are you up to something? Maybe you just want to get hold of a spare item of mass consumption?”

“Dadgummit,” I said. “I lost it.”

“Dadgummit,” I said. “I lost it.”

He said, “Of course, I can’t just take your word for it. Now if you brought me a certificate from the tram depot saying you lost a galosh, then I’d give you a document. Otherwise I can’t.”

I said, “But they sent me to you.”

And he said, “Well, in that case write a statement.”

I said, “What should I write there?”

“Write: On this date the galosh disappeared.

And so on. I’ll give you,” he said, “a receipt of constant residence pending clarification.” I wrote the statement.

The next day I got a factual certificate. I took this certificate and went to the bureau. And, just imagine, when I got there, without any running around and without any red tape, they gave me my galosh.

No sooner had I put the galosh on my foot than I was filled with tenderness. Just look, I thought, how the people here work! In some other place would they really have spent so much effort on my galosh?

They’d have thrown it out in no time. But here I barely spent a week running around and they gave it back.

One thing vexes me—while I was running around this week I lost the first galosh. I had it bundled up under my arm the whole time and I don’t remember where I left it. The thing is—it wasn’t on the tram. It’s a bad job I didn’t leave it on the tram. Wherever am I supposed to look for it?

On the other hand I do have the other galosh. I’ve put it on the dresser.

Once in a while when things get dull, I look at the galosh and for some reason I get a nice and easy feeling inside.

“How great,” I thought, “the bureau works!”

I’ll save this galosh as a memento. Someday my descendants can admire it.

Don't forget to vote for the post if you liked it, follow for more of my post logs, and leave a comment to let me know what you think!

If I had a million SP I would have given you an 100% upvote right now. Wao! Such creativity needs an hype.

I love the way you switch words and the uniqueness in the plotting

really,am thrilled..

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.shortstoryproject.com/poverty-the-galosh/

Yeah pictures in a word.