Myth & Literature

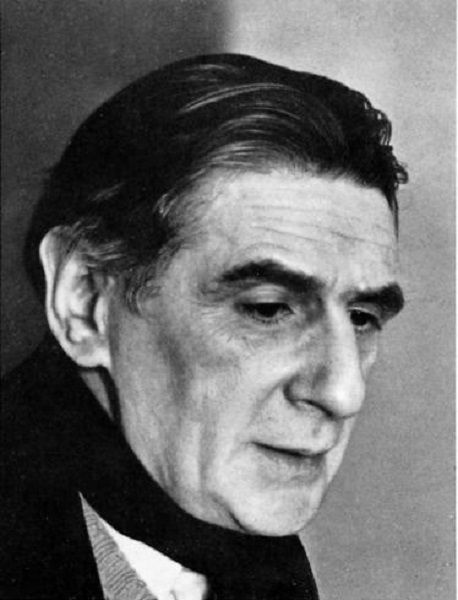

"Homer has reached the limit after which the myth is transformed into literature, and Tolstoy, the other frontier, after which literature is once again a myth." This view of the Austrian writer Hermann Broch, who lived from 1866 to 1951, was developed in his essay "Myth and Style of Adulthood", published in 1947. According to Broch, between the sprouting and the return to him - between Homer and Tolstoy - the whole story of European literature extends. The return of human expression to the mythical beginning reminds us of a return home after a long absence. And this is already a sign of the twilight preceding the fall of the night. The myth has undoubtedly some traits of both life phases - of childhood and of late age, and at both stages the main striving of the style is to express only the essential: at the beginning, because the sphere of subjectivity has not yet been discovered, and at the end , because this sphere is already overgrown.

The myth and the literature through the eyes of Hermann Broch

This "age of maturity", according to Broch, is not always the result of the accumulated years; it is a kind of creative gift: the phrase is less and less based on the traditional vocabulary of the means of expression. The creator, gifted and cursed to get to the age of mature age, can no longer be content with the conventions offered by the age. For if he wants to express in his works the full face of his time, he can not remain in it, but he has to choose the point of view outside of him. The artist who has reached this peak is already standing above and beyond art. Indeed, he continues to create art, but all the minor, specific problems usually dealt with by secular art are no longer of interest to him; even though the title of "creator" acquires another, a higher sense than any other, in behavior he is more akin to the scholar because of their common desire to encompass the world as a whole, although his abstraction is born above all with myth . Deeply significant is the fact, "said Broch," that most of the works created in the mature age are mythological, and some of them, such as the Goethe Faust, for example, by the abundance of the symbols contained therein, become new members the mythological pantheon of mankind. And this pantheon grows with the achievements of the "great style" of the classics. This is how Hermann Broch sees this development in the history of European spirituality:

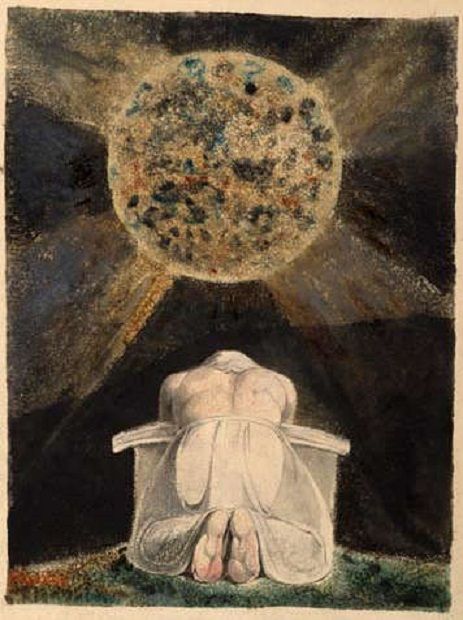

The "great style" of Christian culture reached its apogee in the Pre-Renaissance era, that is, at the time when the mystics were paving the way for the Protestant Revolution. She opposed the hierarchical worldview of myth. Indeed, the Christian still acted within this myth, but he had already realized that the myth embodied by him was the fruit of his own spirit, that he was a creation that the Lord had through his immediate manifestation of mercy breathed into his soul. Thanks to this discovery, man can reject the inherited hierarchy of external reality and begin building in his own "self" his image of the world. In this radical change of the angle of view, man as an individual acquires a completely new meaning; until then, he was reduced to just a picture of myth, and now he saw that he was no longer forced to stay in the periphery but was placed in that central place in the system where he could already catch up with building a humanitarian world around his own center. But this casts another light on the "big style" phenomenon - it occurs when the shell of the closed system is about to break in order to give birth to a new system, that is, at a time when all forms of the old system are stable enough and it is still in a position to secure the validity of the myth derived from its beliefs, but the new system, driven by hope and the pursuit of publicity, must now legally create a new form specific to it: this is precisely the "great style" .

The great style expresses both confidence and revolution; it can only exist as long as it burns the living flame of its immanent revolutionary tendency, because ultimately it is also destined to be buried in a system closed to the one from which it originated. The Protestant era and the Protestant image of the world also had their "great style", which was even one of the greatest in the history of mankind: in painting he was represented by the Flemish school, in music - by Bach and his predecessors in literature - from Milton, and in philosophy later, from Kant, but we see it as a creation of Protestant scholasticism rather than a style. But here, as in all previous cases, the "great style" already announces the end of the Protestant era, as the system that has been locked into confinement has yet to be broken by another revolutionary act. This fully confirmed the intuitive prophecy of Catholicism: in the eyes of the church, the Protestant rebellion was the first step towards the collapse of the Christian unity of the West, to the heretical secularity of the human spirit - and that was indeed so. In an irreversible process of decay that lasted from the 18th to the 20th century, the Western thought structure lost its Christian center. These hundred and fifty years of decay have created a whole new worldview in man, called romanticism. While the value system is in action and its image in the world remains undamaged, man is able to solve his personal problems in traditional frames; but in times of value destruction, he can find such solutions only as in each case he is building a new image of the world. The imperative need to recreate the totality of the world on a case-by-case basis and for each individual can be seen as an essential feature of Romanticism; of course, the romantic worldview could never be achieved without the preparatory work of Protestantism, according to whose religious postulates the human soul is in direct contact with God and his creation.

The dogma of Protestantism gives the human soul much greater autonomy than Catholicism, and in Romanticism this autonomy acquires an absolute character. That is why the art of Romanticism, even if it is the work of a great artist, can never rise to the "great style", which always implies the validity of a common myth, while the validity of every image of the world, corresponding to only one particular case , is limited by the dimensions of the autonomous soul of its creator. Marked with the stain of this extreme uncertainty, the romantic artist seeks salvation in his typical state of longing, primarily in the longing for the religious unity of the past epochs. Driven by the desire to find an absolute solution to his problems and the insight that Protestantism is the main culprit for his precarious position, the romantic guides some way back to Catholicism and the protection of the church. Every real creator in a sense is a rebel, because the need to build his own image of the world makes him break the closed system that created him; at the same time, however, he is forced to realize that this revolutionary deed is not in itself sufficient, and that he is obliged to build the skeleton of a new global model in general. This is precisely what happens through a STYLE OF THE BIG AGE, reaching a level of consciousness that can only be defined as super-religious. Up to this lofty peak, Bach rises in his later works, and Goethe and Beethoven, even though they both worked during an era in which the religious value system has already been destroyed and had to attain the abstractness of the environs of Romanticism.

But just by paving the way from Romanticism to abstractness, they became ancestors in the most real sense of the word; the same applies to Tolstoy, which was even more radical. Although "War and Peace" can not in any case be regarded as a late work, romanticism has already been unambiguously overcome, and the style of adulthood is outlined by the total model image of the world. In its radicality, Tolstoy was not content with the artistic reincarnation of the myth, and unlike Goethe and Beethoven, who, despite their human majesty, were above all creators, he headed for a higher totality, representing us more and less building a completely abstract theogony. Because the mature age that Tolstoy finally achieved had set an end other than Homer's; she was born with Hesiod and Solon, as achieving it meant a complete merger of Myth and art. " Herman Broch's reflections on myth and maturity are typical of European thought after the end of World War II. The Austrian writer considers blasphemy to compare our time to the era of Homeric epics. Because, losing the religious core value, our modern world-or at least the West-has fallen into a state of complete disintegration of values, where each individual value fights with everyone else by striving to conquer them. At the same time, there is constantly growing dissatisfaction with Romanticism. If art can and should continue to exist, its task is to strive for the essentials, thus creating a counterbalance to the indescribable misery of the world. But by putting this task before the art, the age of decay simultaneously calls on the artist to reach the age of maturity, the style of essence and unconditional abstraction, Hermann Bruch concludes.

The intrusive touch points between the arts, defining the abstractionism common to all of them, which determines their general age of maturity, could be considered as characteristic features of our age. At the same time, they explain why there is a close proximity between so many different artists as Picasso, Stravinsky and Joyce, whose relationship is remarkable not only as a result but also as a parallel development. Significantly, Joyce finds it necessary to return to Homer's "Odyssey". And although this return to myth - as already outlined by Richard Wagner's musical drama - nowhere else attains such artistic perfection as in Joyce's work, it should be regarded as a typical trend in modern literature: the revival of biblical themes, for example in novels of Thomas Mann, is an irrefutable proof of the cruel power with which the myth today again takes the floor in literature. But it's just a return to the old forms of myth, and it is not yet a NEW myth. Still, Hermann Broch accepts that the first incarnation of the new myth has already been made in the works of Franz Kafka. By capturing intuitively a new cosmogony, anticipating the new theogony that is about to be created, in the struggle with his love for literature and his disgust of literature, desperate by the doom of all artistic aspirations, Kafka ultimately comes to the decision to withdraw from literature and the last his will is to destroy all his work, because - Hermann Broch ends - it is Kafka, like Tolstoy, he perceives the new world totality that he was judged by myth.

Very clever! Cheers!