Why would you swim in cold water?

For the last couple years I've been swimming in a bay on the west coast USA. Here is the blog post I wanted to share from an Irish swimmer who writes at loneswimmer.com. He really really explains cold water swimming ( my addiction ) well.

"I’ve written so much about the mechanics, physiology and psychology of cold water swimming, but I haven’t addressed the underlying assumption that are taken for granted. So why would you swim in cold water? (And let’s set aside any possible health impacts for this discussion).

In the middle of Irish summer when (or some years, if) the water reaches a glorious 16 Celsius, and hardened long distance swimmers can seemingly swim forever, it’s very easy to imagine swimming easily through the cold water of winter.

October passes with water temperatures between 10 and 12 degrees, where we still feel comfortable. An occasional day may even be warm.

November arrives with the first real days of winter from a sea-swimmer’s perspective. The water will almost certainly drop to under ten degrees, occasionally at first, clawing back above 10 C but inexorably the average always dropping. I’ve previously called the sub-10 degree decrease The Big Drop. If you are hardened though, ten degrees is still fine, you can certainly swim for an hour if you are acclimatised. But before the end of November at least one of the days that is real winter will unveil itself. Hard frost on the vegetation before you leave the house, or freezing fog. Having to consider ice on the drive to the coast.

The wind. That bitterly cold north or east wind that impales when you arrive and exit the car, instantly seeking out fingers, ears, exposed flesh. It leaves you cold and uncomfortable before you even get changed. The occasional visitor asks you in dumbfounded amazement if you are actually going to swim? I’ve had entire families stand around waiting to see me get in, assuming I’ll turn around and get out immediately, when in fact I swim off past the Comolees, out of sight, and they are long gone, back to their warm cars, before I finally emerge.

Years of cycling, running, surfing and open water swimming have left me convinced November is one of the worst months in Ireland. It is invariably one of the wettest of the year, (no mean feat in Ireland) and that couples with wind and cold, and suddenly shortened days to make it profoundly grim and grey.

The certainty of those summer days, when you’ve dismissed winter swimming as something you do with ease, evaporates. Each swimming day done becomes part of a year’s long process or project, but not easy. All the difficulties we forget, even in Ireland cool damp summers, return. We finally remember that there is a question that we don’t ask in summer: Why, given all the discomfort and even pain, would we swim in such horrible conditions, when the act of immersion carries actual physical pain, and continued swimming can (and probably will) lead to hypothermia? Why do we put ourselves through that?

In summer and autumn we often even forget that question exists. But it’s manifest when you are balancing on a car mat trying to stay off the freezing concrete as long as possible, metres from a two metre choppy swell driven by an easterly wind, struggling into a pair of Speedos, while you keep a warm cap on to keep the wind off your head as long as possible.

There are two simple answers.

We’ve discussed the shutting off of blood in the skin and extremities; a swimmer who emerges from cold water will have the warm core blood flow back into those areas. While I’ve cautioned repeatedly about the dangers of Afterdrop, the sudden post-swim drop in body temperature caused by cold blood entering the core, the fact warm blood flowing back into your extremities also carries with it a sense of euphoria every time, the first powerful answer. Your skin and muscles tingle and feel powerful and you feel completely alive. And unlike any substance that produces a euphoric effect, you don’t need to keep upping the dosage. Once the water is cold, you will always feel a post-swim euphoria.

The second is also obvious in a way. Despite all the trepidation before a cold swim, the discomfort of those first few minutes, once those are past, when you are out there in the winter, knowing almost everyone else would never consider doing what you are doing, that itself is a powerful feeling. You feel strong, confident and even dare I say, invincible. Those are not insignificant feelings, and always easy to achieve. Something that makes us feel good about ourselves must be good, there are too many things in the world that make us feel otherwise.

In December the sunlight is lower, the light levels are poor on dull days, but some days dawn with a glittering intensity and the water is calm and cold and the air is clear and you are the only person alive in the world.

Why swim in cold water? Why not."

Swimming in cold water increases your brown fat. Brown fat generates heat so you don't need to shiver at all. It also burns lots of calories to keep you warm if you sleep in a cooler environment - so you can put off weight while sleeping.

Nice to read an article in English with metric units.

I do notice I get much hotter during the night after a swim, so that I often end up with just a sheet covering me until early morning. So something must be happening! But when I am in long enough, or the water is cold enough, I still shiver afterwards. I often do a short run back to my apartment, and that does help. Definitely for swimmers with more body fat than me ( and cold water swimmers do tend to have that ) It might be true.

Wikipedia article

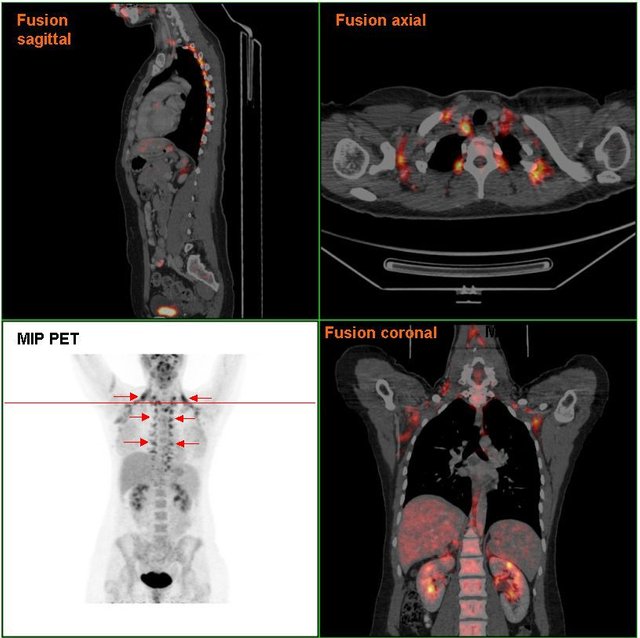

Brown adipose tissue in a woman shown in a PET/CT exam

Swimming in cold water has been something that has been around for centuries including many religions as it's believed to have a some spiritual cleansing benefits.

I'm land locked, so don't get to swim in cold water too often, but thoroughly enjoy a nice cold shower every morning. Stimulates the brain, and provides a great start to the day.