Local Values Frames in TTRPGs

(cross-posted from my substack)

Local Values Frames in TTRPGs

Building on the ideas from C. Thi Nguyen's "Games: Agency as Art" and applying them to TTRPG Theory

When I read C. Thi Nguyen’s philosophy-of-games book Games: Agency as Art in late 2021 I found several ideas in it to be interesting and valuable. The book is grounded in academic philosophy, and in attempting to sidestep getting stuck in arguments about edge-cases or the comprehensiveness of definitions about what counts as a game Nguyen makes the philosophical move of saying he’s restricting his analysis to “Suitsian” games, i.e. those that conform to the definition proposed by philosopher Bernard Suits in The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia. In the process I think he ends up making too big a deal of a “means vs. ends” distinction, but points toward a way of looking at games that I find quite compelling.

What does it mean? Where does it end?

Suits offered two definitions of “game”, a short version: “the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles”, and a long version:

To play a game is to attempt to achieve a specific state of affairs [prelusory goal], using only means permitted by rules [lusory means], where the rules prohibit use of more efficient in favour of less efficient means [constitutive rules], and where the rules are accepted just because they make possible such activity [lusory attitude].

Nguyen takes that and observes:

In ordinary practical life, we usually take the means for the sake of the ends. But in games, we can take up an end for the sake of the means. Playing games can be a motivational inversion of ordinary life.

While the technique of making a point by linguistically inverting something does tend to seem compelling, I think this overestimates how much we care about “ends” in our everyday life. I think it’s more common for us to take roles or engage in practices without focusing on the ends. When prompted we can often articulate a supposed end that we’re pursuing, but often this ends up being more a rationalization than a reason. But even though I disagree in that narrow sense, I agree in the broader sense: playing a game involves stepping into a local values frame. For example, outside of a game of basketball the score doesn’t matter, inside it matters a great deal. Caring about the score matters to the way the game works. Outside of the basketball game getting balls through hoops is just an arbitrary thing, inside it’s the way you get points and therefore deeply important. This process of adopting the temporary, local values of the game and letting those values go when it’s done is arguably what the metaphor of “stepping into the magic circle” is about.

I think it makes more sense to talk in terms of “values frames” than in terms of goals or ends because I think it’s more universal and applicable, allowing us to broaden out from the Suitsian constraint. Explicit goals are one way of establishing values as relevant (get the most points, earn the most profit, etc.), but not the only way. The fact that they concisely and effectively communicate values makes them excellent tools for game designers, but I think the history of tabletop RPGs shows us that other values-establishing elements can be in play.

Psi*Run allows an explicit example

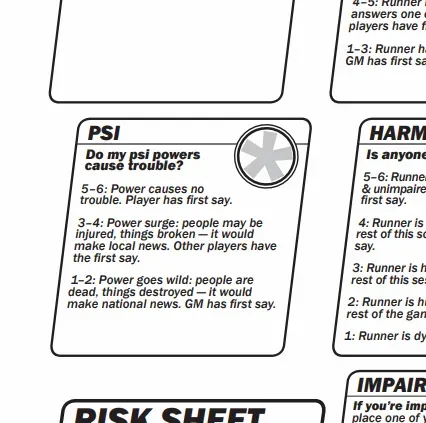

The indie TTRPG Psi*Run has “Otherkind Dice” as its core mechanic, so it very clearly illustrates trading off values as a core element of play. In the game you roll a handful of six-sided dice and need to assign each one to a variety of categories, like whether your character achieves their goal or whether the shadowy agency that’s chasing the characters gets closer to catching them. Since dice are random you’re unlikely to get good results on every one, so which categories you assign good or bad results to matters for how things proceed in the game. One of the categories, Psi, involves collateral damage:

Do my psi powers cause trouble?

5–6: Power causes no trouble. Player has first say.

3–4: Power surge: people may be injured, things broken — it would make local news. Other players have the first say.

1–2: Power goes wild: people are dead, things destroyed — it would make national news. GM has first say

In order to actually be fully engaged with the game you need to care about what’s happening to the people and places around the main characters, the same way you would when reading a comic book or watching a movie or TV show. If you look at that option and are confused, asking “Why would I ever waste a good die on that, it doesn’t affect my character at all?”, then you probably aren’t engaging the way the game needs you to engage in order for it to function properly (you can certainly play a character that doesn’t care, but you as a player need to care). The game expects the dice tradeoff to be a meaningful decision, and for the effects the characters’ powers have on the world around them to be weighty and meaningful in the way they would in a glitchy-powers superhero story. The game doesn’t do this by giving you an explicit goal to minimize collateral damage, it uses softer implicit methods to make “the fate of innocent bystanders” feel like it’s relevant to the story being experienced by playing the game, the same way that other media do.

Other methods can be less reliable

In our normal lives we rarely communicate about values by laying out explicit, simple goals or principles. Our values are communicated via the complicated stew of our culture: the stories we tell, the role models we respect, which actions are treated as praiseworthy vs. transgressive, etc. Since our “values hardware” can operate with values communicated in myriad ways it would be weird if explicit goals were the only thing that worked for stepping into a magic circle. With TTRPGs a lot of that soft transmission happens via art, setting design, which players are treated as admirable, what kinds of behaviors are scorned, etc., just like in regular culture.

Since TTRPGs were originally created by evolving and drifting other games rather than engineered from well-understood first principles it shouldn’t be surprising that there weren’t always clear identifiers about which parts were functional or load-bearing and which parts could be treated as decorative. Just like different people can interpret different “messages” from a novel, different people can come away with different ideas of what the game even is when reading a game like early D&D. The “local values frame” is a big part of making a game work the way it does, so if you see different things as the relevant values from someone else then you may as well be playing a different game, since they’ll work differently.

The way it has been done isn’t how it must be done

Observing that “soft” methods sometimes lead to different interpretations by players doesn’t mean they need to be abandoned, any more than observing that it’s possible to write an essay with muddled points or an uncompelling case is an argument against the essay as a form. There’s nothing intrinsically good or bad about doing things explicitly, implicitly, or in some combination, and TTRPGs as a medium are probably more amenable to implicit approaches than other types of games, so it makes sense to explore that aspect of the medium. But the idea that establishing the local values frame is something that a game’s design (including setting design, etc.) is doing may be a useful analytical lens. It’s not a recipe that guarantees good design, it’s a way to think about an aspect of how games work.

Relating this to previous RPG Theorizing

While The Forge was notoriously hard to pin down about exactly what some of their concepts meant, I suspect they were grasping toward the idea of values frames when discussing “creative agenda” and “coherence”. A lot of that boiled down to the question of mutual intelligibility — if I can’t see what you care about when you’re making your contributions it’s hard for me to consistently see your contributions as valuable signal rather than meaningless noise (and vice versa), which is a recipe for unpleasant interactions.

Vincent Baker shifted to thinking that it makes more sense to focus on the “object of the game”. As with my earlier objections to the means/ends stuff, I think he’s right in the big picture sense that the most important thing is looking at how players are oriented and how values are established in particular games rather than worrying about “taxonomic families” like G, N, or S, but I think he is slightly mistaken in thinking that “the object of the game” is the thing that does that rather than being one good tool that can do that.