Thoughts on "Value Capture"

(cross-posted from my SubStack)

Thoughts on "Value Capture"

A new philosophy paper talks about how big clear values can crowd out particular nuanced ones

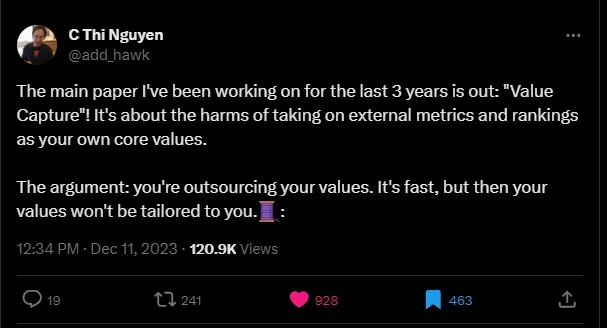

Since reading Games: Agency as Art I’ve been following philosopher C. Thi Nguyen on twitter, so I recently saw his tweet thread about his new paper, Value Capture.

While I didn’t fully agree with the ideas presented in his book, there was I lot I liked and I found it thought-provoking. Since the ideas I’ve found most interesting were related to “values” I was intrigued to read this paper. I don’t fully agree with everything in this, either, but there is a lot of stuff worth thinking about, and some stuff that may be especially relevant to RPG Theory, game design, and TTRPG discourse.

A brief summary

The paper focuses on the phenomenon where some simplified large-organization-level value comes to dominate and essentially replace particularized, nuanced values. This can happen with both individuals and organizations. One example he gives to illustrate the point is that people can start using a FitBit to help them get healthier, but then some people end up fixating on their stepcount exclusively rather than on a robust sense of what it means to be healthy. Another example is that once US News and World Report began tracking and ranking law schools most of those schools started chasing that metric, and in effect ended up “optimizing away” elements of their unique character or focus in pursuit of a higher rank, and prospective law students started caring more about getting into the best-ranked school they could rather than the more intangible factors like location or culture.

While he largely frames this issue as a negative he does note that getting values from external sources is entirely normal and expected thing – humans are social animals, our norms and customs aren’t spontaneously self-caused. His point isn’t as crude as “things from outside the self are bad”, but rather that things that work to communicate at a larger scale are, by necessity, stripped of local context and standardized. That has clear upsides (such as making it possible to work in groups toward shared goals) but also less obvious costs. The paper argues that we get more human flourishing when our values are well-matched to our individual natures and particular context, so if our values get snap-to-grid-ed to a value set optimized for a large organization there is going to be less flourishing than there otherwise could be.

The paper primarily lays the tendency to be captured by these values (rather than them serving as an external tool like a lingua franca) at the feet of cognitive fluency, communicability, and value clarity. Working with a simplified and often quantified value system often feels good – we can feel that we’re smartly doing the right thing that’s valued by others rather than operating within a fuzzier, unverified scaffold of our own making.

And value clarity effect becomes even more powerful when that clarity is standardized. After all, the existential burden of our complex values is not merely a personal affair; we have to deal with the buzzing tangle of everybody else’s values, too. Navigating this overwhelming plurality – understanding other people’s values and explaining our own – can be grueling. There is, so often, a vast gap between our values. Try explaining to another person your profound love of some weird old comedy, or why a sour cabbage casserole makes you feel so comforted on the bleakest of days. Try explaining why a particularly acid passage of Elizabeth Anscombe’s fills you with such glee, or why you never quite got along with running, but rock climbing makes you feel so amazing. Sometimes we can make ourselves understood, but often we cannot. So much of our sense of value arises from our particular experiences, the long life we’ve led, our twisty paths to self-understanding and world-loving — that explaining the whole mess to others is often beyond our capacities.

Some Criticisms

While I think there’s a lot that’s worthwhile about this paper I do have some criticisms. First, I’m not 100% sure about this, but I think one of the examples used in the cognitive fluency argument (related to font legibility) hasn’t fared well in the replication crisis in psychology.

Second, I’m not fond of his “gamification” argument. Basically he’s asserting that clear values are a thing that games have, and games are fun, so that’s one explanation for why clear values seem appealing. But I think this tends to get gamification backwards – the most common tools of gamification like achievements and leaderboards are more like the workification of games, it’s quite common for these things to make playing a game feel like a grind! (Maybe this deserves a longer post, but I think the “gamification” model as commonly understood is deeply flawed – particular game parts don’t have “fun” in them that you can naively bolt on to other systems to increase the amount of fun in them, just like you can’t reliably make something beautiful by slapping segments of beautiful paintings onto it. Making a game fun is a complex art, not just dumping a bag of tricks onto a sticky substrate.)

I also think the paper would benefit from talking more about reasons to think that a diversity of values could be a good thing, analogous to the way a diverse ecosystem tends to be more resilient than a monoculture. In this way of thinking our human ability to internalize, adapt, and remix values could be a memetic parallel to the things in biological evolution like the genetic mixing of sexual reproduction. I think the paper might also benefit from being explicit that nuanced and particularized values aren’t always good things, for example an old boys’ network probably has more nuanced and custom-tailored values than a more open market but that doesn’t make them good.

Parallels to RPG Theory: Clouds and Boxes

In 2009, game designer Vincent Baker wrote an influential series of posts about “Clouds and Boxes” that talked about trends that seemed to be gaining popularity in the indie TTRPG design scene at the time and some problems with them. I don’t recommend reading the posts themselves since there was a lot of miscommunication[1], but the gist of it was that caring about “the fiction”, i.e. what was actually happening in the imaginary world during play, had a tendency to drift toward unimportance if those things were coupled with mechanical bits that worked together very smoothly – the action would go mechanical-bit-to-mechanical-bit (box to box) rather than involve the things you were imagining (the cloud). So, for example, if your character has a set of attack actions that correspond to some different dice values that will end up reducing a monster’s hit points, even if you’re technically supposed to imagine and describe some particular thing your character is doing when you invoke those attack actions you’ll have the tendency to drift toward just the mechanical part since it seems like that’s what “really matters”. These ideas were the beginning of the “fiction first” movement[2] in the Story Games scene, a desire to make sure that mechanics were interfacing with things in the fiction, not just other mechanical bits.

This drifting from nuanced particulars to easily-communicated, quantified, explicit factors struck me as similar to the phenomenon discussed in the paper, with the “values capture” of the paper perhaps being the more generalized phenomenon of which the “box to box” problem is a specific example: Even if you start out valuing a richly imagined situation in the game, an easy-to-engage-with shared language of mechanics can pull you toward thinking only in those terms.

I think we can also see values capture manifesting in TTRPG culture, for example in the Story Games scene there was a drift from playing and talking about the nuances of a broad array of different games toward everyone wanting to play The New Hotness™[3]. Or the phenomenon of people who are theoretically in the indie games space going on and on about D&D on social media since that’s what “gets engagement”. The desire for crisp externalization could also be related to the phenomenon of people wanting to treat a drifted, house-ruled, or idiosyncratically-interpreted version of a game as “the same game” as other people are playing rather than as a different game, and why “supported product lines” tend to be a thing people care about even if the existence of hypothetical new products (or lack thereof) can’t materially influence the game you’re playing today.

Can we use it?

Since I’m mostly on board with the idea that the paper’s topic is worthwhile to consider, at least at the broad outline level, my game designer mind also turns to the question of whether or not we can leverage it rather than being passive subjects of it. And I think we may already be doing it to some extent. For example, one of the things that a game like Apocalypse World needs to do to function properly is prevent people from imposing “a story” onto the game – something that many other games tell GMs is a core part of their role and that they therefore may be bringing into the game with them as an inchoate value of what it means to be a “good GM”. AW partly tries to avoid this by explicitly saying “don’t do that”. But it also has procedures like Threat Maps that could be “intercepting” some of the things that tend to feed into “story” sensibilities and thus ameliorate that tendency. I also wonder if games that give a GM an explicit budget for things like rerolls have a tendency to undermine the cultural practice of fudging die rolls.

Avenues to explore

The paper is focusing on this phenomenon as a whole, but my instinct is to think that it’s worthwhile to try to tease things apart in a little more depth. How much does the inside/outside distinction matter? What does it mean for values to be “simpler”? Is that analogous to having only a single dimension vs having multiple dimensions?[4] Is the fuzziness of more “organic” values beneficial in and of itself, or is that just a common association? Can you mix and match? If you focus an a simple, quantified personal value will that tend to “capture” your values-set away from your local culture or community, even if that’s “bigger”? Are there ways to do “simple” org-level values that don’t squash nuanced particulars (for example, it seems to me that we can use things like the RGB color space without squeezing the nuance or particular qualities out of color)? Is it impossible the communicate the nuanced values embedded in a play culture via a game’s rules, or is it just tricky to do it right? What are the actual mechanisms we could use to sustain the “values federalism” the paper advocates?

I also wonder if the concept as presented is too one-directional. It seems to me that we might view a micromanaging boss as someone with particularized, nuanced, unexpressed values who usually resists management via goals and objectives. If clear, org-level values are so seductive why do so many managers end up reverting to micromanaging when left to their own devices?

Conclusion

I think the paper raises some interesting ideas to think about, both with respect to broader society and also in the more narrow world of TTRPG design and RPG Theory.

[1] My take on it is that because Vincent was talking in a complicated way people assumed he must be talking about a complicated concept, and his attempt to reference simple examples were often taken as metaphors for something grander that people couldn’t yet grasp rather than things that were actually supposed to be simple.

[2] As sometimes happens in politics, the popularity of “fiction first” as a rallying phrase outpaced the more complex and nuanced body of ideas behind it such that it’s now pretty unclear what people mean if they say something is “fiction first”.

[3] The Story Games community had a tendency to notice problems in the social dynamic and talk about them in a collectively-self-deprecating way while also not doing anything about them.

[4] I have a post that I’ve been trying to figure out how to write that I’ve been mentally expressing in terms of values as dimensions and what happens when one of those values collapses. Since this paper is talking about values changing in a way that tends toward simplicity I’m not completely sure whether it’s a similar thing to what I’ve been thinking about or a different thing.

@tipu curate

;) Holisss...

--

This is a manual curation from the @tipU Curation Project.

Upvoted 👌 (Mana: 4/8) Get profit votes with @tipU :)