Lesson sequencing for teaching science (Part 3 - Guided application and linking knowledge)

Click here to see other posts in this series:

The background context

Part 1 of how I sequence my lessons (time and interleaving)

Part 2 of how I sequence my lessons (lesson types in the sequence)

Part 3 (this page)

Part 4 of how I sequence my lessons (Application of knowledge)

What happens in my guided application lessons?

First of all, I like to exploit the process of elaboration. In my classes, I tend to want students to draw out what they know of a specific topic on A3 paper. The can start with core content and then start adding peripheral details. They can use arrows to link concepts and draw simple images. Importantly, we can find gaps in knowledge as students talk to each other and discover links that others have, but they don't, on their paper. I often do this when I think it is necessary, maybe we have covered a lot of new content, or maybe I feel that the students have some gaps in their knowledge that aren't allowing them to make the necessary links. I plan to do it at least once per topic.

But I still want more, elaboration is good for practice and is a beginning point for practising linking their knowledge.

Guided application questions

Craig Barton @mrbartonmaths argues that we cannot kill students with core questions repeatedly over many weeks (or even years if future teachers want to practice content that was covered by an earlier teacher); they need new practice material that focuses their attention on what needs to be practiced, but in new and rich ways.

Craig introduced me to Colin Foster’s “mathematical études” when I listened to their interview podcast, Craig says that it is similar to what he calls "Purposeful Practice". These offer a solution to this problem in teaching maths. But I wanted something for science, and I wanted it to be defined and clear in my mind so that I could produce lots of practice material for each topic.

I also liked Dr Tony Sherborne’s new “Mastery Practice Book” which has many worked examples of how to approach an application of knowledge question. These worked examples show students how they must first think of what knowledge they have that can be used to answer the specific application of knowledge question. It then has questions for following the same format of

- Identify what the question is asking you to think about

- Recall the knowledge you have on this topic

- Write your answer

But I still think that students struggle to relate their knowledge to new contexts and in low-working-memory-load manner. In other words, its a good idea asking students to think about what they know on a topic before answering, and I encourage it, but I think we can add another step before this, because I think students struggle to recognise that they have knowledge on a topic; they don't realise that the knowledge they have can be applied to this context, there is a missing link, so they just go blank and think they don't know anything.

I have started developing question sets which I call “guided application”. This isn’t perfect, as I’m still not sure how much it really helps the students recognise the links between the knowledge they have and the problem at hand.

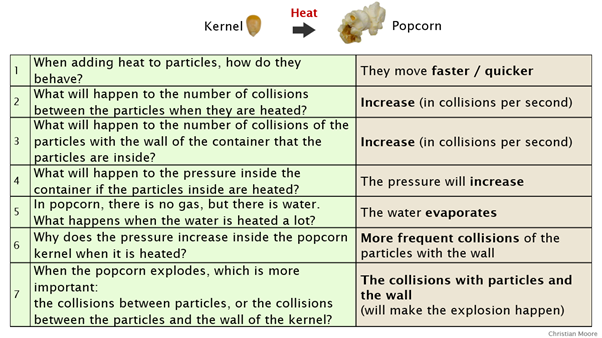

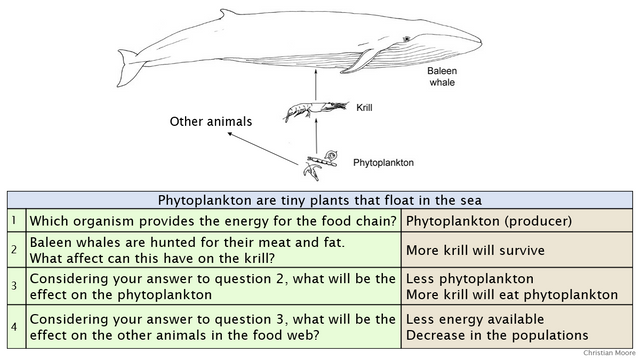

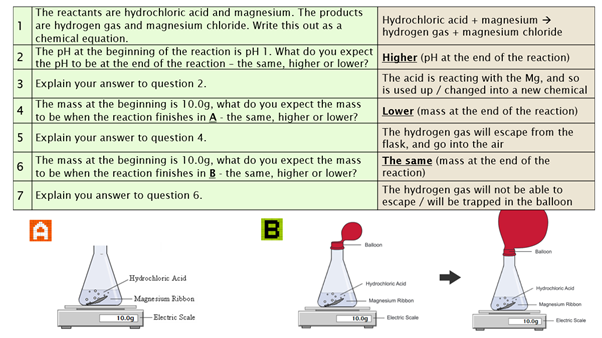

My guided application questions are on a specific context, maybe something that could easily be an extended answer question for application of knowledge (as it wasn’t the context in which we learnt the knowledge), but here, my job is to scaffold their answers and focus their working memory on retrieving the appropriate knowledge for this context. So, I could break down the extended answer into individual short-answer questions. In other words, the individual short questions pull out the knowledge required to answer a full extended-answer application question, in a step-by-step fashion. The questions are in table format to reduce extraneous load.

I hope this extra practice will cover three problems:

- I can continually give students retrieval practice without excessively and repeatedly showing the same "core questions".

- The students can get practice with recognising that these schemas of knowledge can be linked to other contexts.

- The practice is "richer" than just carrying out "core questions" and so students should have to think a little more (desirable difficulties)

Here’s some examples of the question and answers slides from my Year 7 course (11-12 years old):

These guided application questions are not too hard to create when you get used to them. They are fantastic in making the teacher think about the core knowledge required to answer certain application questions and therefore help with planning. Once you have a bank of them, you can through in a random practice lesson (type B lesson) some time after finishing the topic where you think students might need some good practice without going back to the core questions (which they have undoubtedly used a lot at home anyway (on top of the retrieval practice they do at the beginning of a lesson).

Click here to see other posts in this series:

The background context

Part 1 of how I sequence my lessons (time and interleaving)

Part 2 of how I sequence my lessons (lesson types in the sequence)

Part 3 (this page)

Part 4 of how I sequence my lessons (Application of knowledge)