How Terrorists Are Creating A New Language

I have been stalking members of the terrorist group Tawheed Network (formerly al-Muhajiroun). I have spied on them over the Internet, and heard much gossip about them in my neighbourhood of Bury Park, Luton.

Unfortunately, I have uncovered something disturbing.

The local jihadis have been cautious since December 2015, when their leader Mohammed Istiak Alamgir was arrested. They no longer run dawah (proselytisation) street-stalls, and they no longer rant at passers-by through megaphones.

But their recalcitrance hasn’t abated. They now consider themselves agents of the Islamic State, or Isis, and have formed online communication channels with foreign jihadis all over the world.

What I have discovered is that the way they communicate is changing, and if we are going to stop them, we must understand how it is changing.

The vast majority of Tawheed Network members originate from the Mirapur region of Kashmir. As a result, they have a particular hatred of the British Empire, whom they ultimately blame for the region’s problems. They despise the fact that they speak the same words as their kuffar (infidel) hosts, seeing it as a sign of colonial domestication. But, unfortunately for them, their parents raised them to speak English as a first language, and they are thus inept at their native “Islamic” languages of Urdu and Arabic.

Their solution has been to mutate the English language into a form more pleasing to them, by combining ordinary Muslim street-slang with scriptural allusions to form an argot that can barely be understood by normal English-speakers — a kind of jihadi Polari. It serves as both a revolt against Britishness and a way to communicate in code, so that more visceral rebellions can be planned with impunity.

The origins of this renegade language, which I will call “Jihadese”, are roughly coeval with the origins of al-Muhajiroun. The group’s founder, Omar Bakri, was known for his playfulness with language. He used to refer to moderate Muslims as “chocolate Muslims” or simply “chocolates”. Counter-extremist and former al-Muhajiroun member Adam Deen told me this term was due to moderate Muslims being perceived as overly sweet toward the kuffar, and “melting in their mouths”.

The term “chocolate” soon evolved into more cutting putdowns like “choc-ice” and “coconut”. These terms are sometimes used by British-Pakistani Islamists to describe Muslims who are “brown on the outside, white on the inside”. It’s a way to evoke memories of colonialism, where whites were the “evil empire” and browns the “righteous resistance”.

Since the nineties, many white people have become jihadis, so the words “coconut” and “choc-ice” have generally fallen out of favour, and been replaced with race-neutral words. The most common Jihadese term for moderate Muslim is now “munafiq”, sometimes abbreviated to “moony”.

The transition from “chocolate” to “moony” within less than a decade illustrates an important point: Jihadese is rapidly evolving, and therefore actively resists efforts by normal English speakers to comprehend it.

Over the years, jihadis have added more and more obscure terms to their vocabulary, deviating further and further from standard English. At the same time, technological innovations have increasingly enabled them to spread their argot across the world, so that it now threatens to become a universal terrorist language.

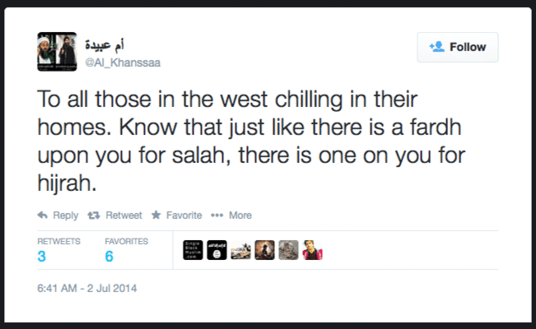

Here is a simple example of how Jihadese is used on Twitter:

The above tweet is a very basic use of Jihadese, mostly composed of standard English. It makes use of the common slang word “chilling” (relaxing), and uses only three Arabic words, “fardh” (obligation), “salah” (prayer), and “hijrah” (migration). However, there is another layer to this last word. While in standard Arabic, “hijrah” refers to migration in general, and the journey Muhammad took from Mecca to Medina in particular, in Jihadese the word means “joining Isis”.

But it’s not just slang and foreign words that set Jihadese apart from common English. The argot also uses unique euphemisms, such as “cake-baking” to refer to bomb-making:

Message sent by Junaid Hussain (aka “TriCk”) using the Jihadese word for bomb-making, “cake-baking”. Curiously, MI6 and GCHQ once hacked into an online al-Qaeda magazine and replaced bomb-making instructions with cake-baking ones.

What makes Jihadese such a slippery language is the diversity of its roots. Someone wishing to understand it needs to be fluent in several different vernaculars, from underworld slang to Quranic metaphor.

Here’s another tweet, showing a more evolved and complex use of Jihadese:

A normal English speaker will have trouble with this sentence, due to its use of Arabic, Internet slang, and oblique terms like “Dream I as a greenbird flying”. Let’s go through it:

“Jihad fard ‘ayn” is Arabic for “combat is compulsory”. “Irja” is a word used for the “quietist” Salafi belief that one can go to paradise without doing what the Qur’an says, as long as one believes in its basic message. “AK” is an abbreviation of “AK-47 machine gun”. “Shahada” means “martyrdom”.

The term “Greenbird” is an interesting scriptural allusion. It refers to an obscure and poetic hadith that says the souls of martyrs enter the hearts of green birds which nest in the chandeliers of paradise.

Ever since Luton jihadi Abu Abdullah al-Britani was killed in a drone strike, jihadis have been referring to their dead fighters as “green birds”.

The term replaced the original Jihadese term for martyr, “72”— a reference to the belief that martyrs are awarded 72 virgins in paradise.

According to a local ex-jihadi who didn’t want to be named, the Jihadese term for being martyred — “getting 72ed” — was eventually regarded as too obvious, and thus forsaken. It was soon replaced with “getting green-birded” and variants thereof, as it was believed non-Muslims would not be well-acquainted with esoteric ahadith.

So with all the terms translated, we can render @JustMuhajirah’s tweet as:

“They keep denying that combat is compulsory

They keep lying

We won’t listen to the Salafi quietists

AK-47 by my side, I will become a martyr or keep trying

I dream of dying in combat and soaring to paradise”

Clearly, statements in Jihadese tend to be more succinct than their English counterparts. This concision lends itself well to social media, particularly Twitter. Not only can a lot be said with it in 140 characters, but its abstract nature means it can be said without triggering word filters or flagging.

To offer an example, this tweet has remained online for nearly a year, even though if interpreted correctly it glorifies martyrdom, a clear breach of Twitter’s terms and conditions:

https://twitter.com/advo_adnan/status/773922454481858560

But Jihadese is not just dangerous because it can disguise its meaning or say a lot with a little; it is also a threat because, as more and more words in its vocabulary mutate, it could change the way its speakers think. As we all know, thoughts are mostly made of language. And so, by simplifying a language, one limits the complexity of one’s thoughts, diminishing the ability to parse nuance, and thereby becoming more susceptible to the simplistic fairy-tale narratives that form the core of jihadi ideology. (This is a concept known as linguistic relativity.)

What makes Jihadese so toxic to consciousness is that it is composed mainly of labels, all of which have positive or negative connotations, giving it a moral absolutism that, like Orwellian Newspeak, splits reality into black and white, good and evil.

An example is the word “rafidah” (“rejecter”). This is a derogation, with strong connotations of treachery. It is also the word that UK terror groups like the Tawheed Network use for “Shia”. Therefore, it is impossible in Jihadese to refer to Shia without implying that they are treacherous.

This weaponised vocabulary is the medium by which many extremists now contemplate and communicate. Its purpose is deception and indoctrination. It is constantly growing, mutating in meaning, becoming ever more alien.

If we are going to defeat the jihadis, we must understand how their language is diverging from ours on social media and on the streets of places like Luton.

If we don’t, then soon enough, we will hear them speak another language, one that everyone in the world understands all too well.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.quilliaminternational.com/how-terrorists-are-creating-a-new-language/