How Sarawakians mitigated Covid-19 using rural ideals

Ever since the Covid-19 pandemic first reared its ugly head last March, Sarawak has been placed under various forms of movement control order (MCO) to mitigate the deadly virus from spreading further.

One of the greatest concerns is to ensure that the rural areas are free from the virus, said Institute of Borneo Studies director Associate Prof Dr Pauline Bala.

She explained that the concern was due to poor healthcare facilities and limited access to remote rural communities.

“If you look at all the policies clearly, it has always been urban bias, whether it's social or economic policies and in terms of technological development; it’s always been urban bias.

“There are gaps that exist between rural and urban including in health dimension. The lack of basic facilities, high poverty rate, huge geographical diversity and environment condition and high illiteracy rate are among big issues that divides the rural from urban areas,” she said in a webinar session entitled ‘Health and Development Issue in Asean’ hosted by Ateneo de Manila University and Institute of Philippine Culture on Tuesday.

Covid-19 in Sarawak

After Sarawak recorded its first three cases on March 13, a few days later, the state reported the first death case in the country on March 17, just one day before the movement control order was enforced.

Throughout the pandemic, cities like Kuching, Miri and Bintulu were profound in accumulating infection case.

This is due to rapid movement among its population.

Fast forward, on Nov 1, Sarawak recorded one new positive case and had accumulated 1,065 cases, with a recovery rate at 96.07 percent.

And to date, there is no case in any of the rural areas in Sarawak.

Looking back, it appears that the strategy taken by Sarawak government to contain the virus from entering into rural areas seems to be successful.

So, what did Sarawak government do that has made this possible whereby the rural areas are almost free from the pandemic?

Pauline, who is a social anthropologist at Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (Unimas) described the good response from the rural community to be in solidarity with the government has contributed in strengthening the force to battling the virus.

She pointed out the collective measures initiated by the rural community deserves the credit.

“Firstly, how the community responds to the measures that have been introduced by the government.

“Secondly, how the government communicates its concern to the people; and thirdly, how the measures are adjusted by the community in response to the government’s initiatives.”

Like other places, Sarawak too had gone through hiccups along the way in learning to handle the pandemic.

Pauline said the implementation of the movement control order was quite messy during the early phase.

“The MCO measure is quite urban bias to a certain degree. And because of that, the local communities themselves have to adjust their own and had come up with their own mechanism on how to adjust two main policy measures within their own cultural setting.

She noted that two issues cropped up – first, on the notion of social distancing and second, the notion of stay at home order.

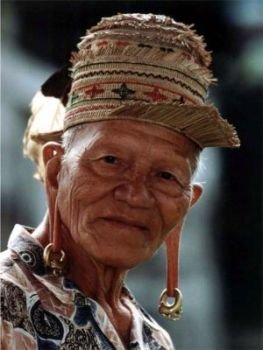

“First is the notion of social distancing. The rural areas in Sarawak are quite different from other places where most of the community are living in longhouses.

“So, when MCO was introduced, the people were required to practise one metre social distancing, which means that you must make sure that one metre distance is kept between persons.

“Basically this is the mechanism to stop the spread of the disease.

“However, in the longhouse, there are multi-generational people living as a community.

“So how do you keep the social distancing and how do you communicate and translate that one metre to the people?

“Some may ask what does one metre means? What kind of measurement they should use?

“In the longhouse, most of them are family members or relatives. For them to impose physical distancing is quite culturally inappropriate.

“This had raised some debates when the measurement was introduced while the communities were trying to make sense within their own setting,” she elaborated.

“Now another one is the stay at home. The notion of home itself is different.

“In urban area, the house is your home. But for many people in rural areas, the mountain, the forest, the river, and even the open space can be their home.

“So, the idea of staying at home also has a different notion in different situation,” she added.

Another measure, she pointed out was the gendered curfew policy where the government only allowed father as the head of household to go out to buy food from the supermarket.

“The initial part of the MCO was the measure that imposed gendered curfew policy where only men were allowed to go to supermarket to buy food for the family.

“And it was a big debate in the media when they found most men didn't quite know what exactly the kitchen stuff that they need to buy.

“The same thing happened in the rural areas. Because there was no supermarket, for them, buying food means that the men will go into the forest to search food and bring back meat for the family.

“Well, for them, the forest is their supermarket. That ‘supermarket’ is quite big, and it might take one day to walk in that ‘supermarket’.

“And that means, men are not expected to come home and bring vegetables from the forest because it is culturally inappropriate as the job is usually carried out by the women, to go to the riverbank, to collect mushroom, vegetables and bamboo shoots to bring home for dinner,” she added.

Pauline further noted that because of this measurement, the local community had come up by themselves to adjust the measure that is applicable within their context.

“The good thing is the communities sit down and try to negotiate the appropriate interpretation of such orders in their situations – in other words, contextualising the measures within the particular community,” she said.”

The power of cultural communication

Communicating effectively to the public, especially to the rural people requires local people who can explain the science of the disease from the community’s perspective.

“They know that Covid-19 is a disease in general. But they have little understanding on the virus itself where some may have no idea how the virus is transmitted.

“Thus, it has led them to equate the virus as ghost, because the virus is something that human cannot see, like ghost too.

“For instance, the Kelabit, they call it ‘adak corona’ which means the corona ghost. Some also have called it as red eye ghost and water ghost.” she highlighted.

The misinterpretation of the virus, Pauline explained could further disrupt the mitigation plan

“For example, understanding the importance of practising good hygiene – there is disconnection in the science of washing hands. They may wonder why they should wash their hands if these are not dirty.

“This requires a lot of professionalism to ensure thatthe rural people have a better understanding of the virus,” she said.

Thus, where is the line between comparative intellectual capacity and relative cultural instinct?

Regardless of the current pandemic that has devoured government systems and countries from almost all parts of the world, humble-little highlanders remain free from the coronavirus