The Tonga Volcano Eruption! Said to be Record SMASHING! New Light shed on how the underwater volcanoes blow? You decide!

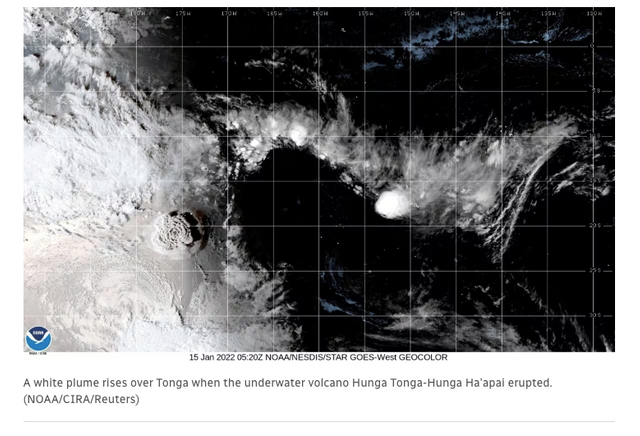

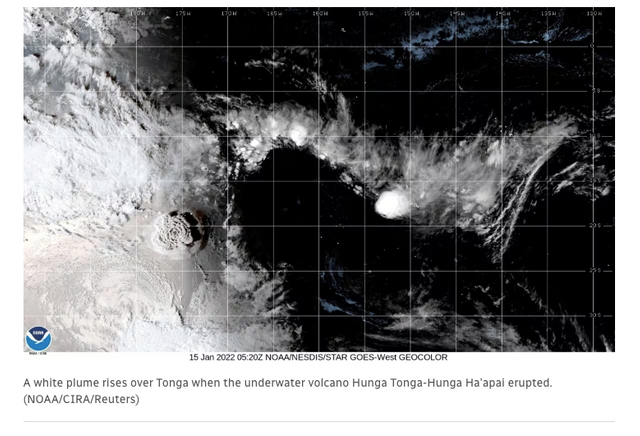

On January 15, 2022 thethe Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano erupted.

off the coast of the tiny island nation of Tonga in the Pacific Ocean, about 2,000 kilometres from New Zealand.

"60-million Olympic-sized swimming pools of saltwater shot upward!"

The volcano — familiar to locals but unknown to most outside of the remote island kingdom — is called Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai. The name refers to two islands that rise about 100 metres above the surface of the Pacific, roughly 65 kilometres north of Tonga's capital, Nuku'alofa.

The volcano has shown on-and-off activity over the years and even centuries with major eruptions recorded as far back as the twelfth century. In December 2021, it began rumbling once again, volcanologist and science writer Robin Andrews told Bob McDonald, host of CBC Radio's Quirks & Quarks.

There were "very gas-rich plumes, but without much material coming up," Andrews said, comparing it to "burping" or "volcanic indigestion." At that time, however, "it wasn't doing anything out of the ordinary."

Then, on January 15, it blew up. The energy released by the blast has been estimated as equivalent of 10 megatons of TNT. That makes it 25,000 times more powerful than the explosion that shook the port of Beirut, Lebanon, in August 2020, Andrews said. The Tonga explosion "was pretty cataclysmic. Even volcanologists who have studied all kinds of eruptions — their jaws dropped."

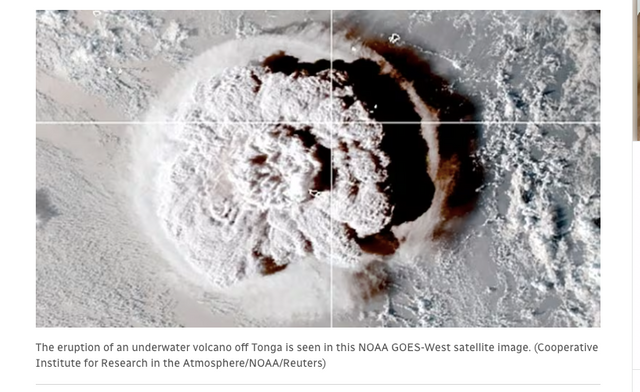

It is said to have produced the largest underwater explosion ever recorded by modern scientific instruments, blasting an enormous amount of water and volcanic gases higher than any other eruption in the satellite era!

According to NOAA, the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration,

Two research papers have now detailed how that water vapor rapidly affected the Earth’s stratosphere between 10 and 31 miles above the surface, causing an unexpectedly large loss of ozone and an unexpectedly rapid formation of aerosols.

“Up until now, sulfur has been the primary focus of research on eruptions,” said Elizabeth Asher, a CIRES research scientist now working at NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory. Asher led one of the two recent studies while at the NOAA’s Chemical Sciences Laboratory. “Studying Hunga Tonga showed that other gases, like water vapor, can have a profound impact on these outcomes.”

Hunga Tonga offered a unique opportunity to observe the immediate atmospheric impacts of a massive volcanic eruption. When news broke of the eruption, Karen Rosenlof, a senior climate scientist at the Chemical Sciences Laboratory, immediately contacted colleagues on the island of La Réunion, which sits in the Indian Ocean 8,000 miles away from Hunga-Tonga but lay directly in the path of the dispersing eruptive plume. Only days later, Asher and several colleagues from CIRES, the University of Houston, and St. Edward’s University were on flights bound for La Réunion carrying miniaturized atmospheric instruments in their baggage.

According to CBC

Kevin Mackay, a marine geologist with New Zealand's National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, spoke with Quirks & Quarks' host, Bob McDonald, about this record-blasting volcano.

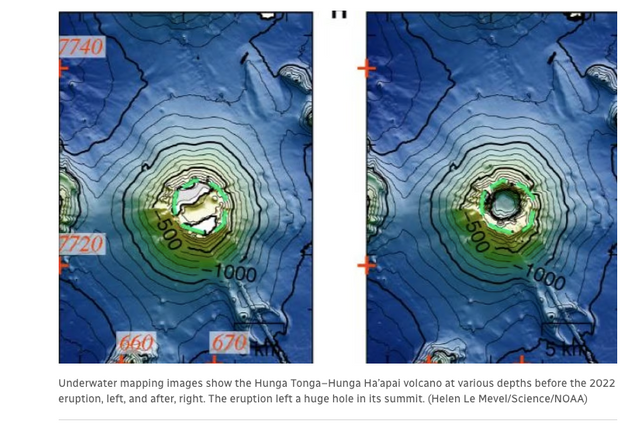

What did the volcano look like in the "before" picture?

It's 2½ kilometres high, about 30 kilometres across. It would be very impressive if you saw it on land, but underwater it's just one of many tens of thousands of very similar features underwater. It's a classic volcanic cone with a very flat top about four kilometres wide and a slight crater on the summit.

Take me back now to that day in 2022 when the volcano erupted. What was it like for you in New Zealand?

It was about 6 p.m. on a summer evening. I was mowing the lawn and I heard what I thought was artillery fire. I thought, "that's odd," because it's not the Queen's birthday or anything special.

It wasn't until I went to the media that I realized what I'd actually heard was the sonic boom of this massive explosion. It actually turned out this volcano produced the largest sound ever recorded in human existence.

Our original assumption was this volcano erupted like a terrestrial volcano. When a volcano blows up, like Mount Saint Helen's, it literally shatters itself.

So when we were mapping this mountain after the eruption, we were expecting to see a large part of the mountain had gone.

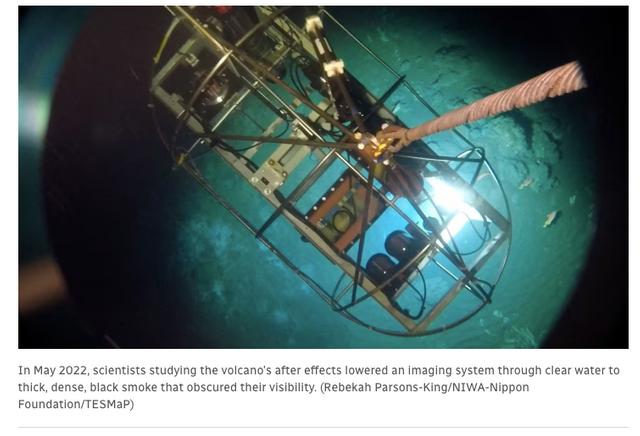

The first thing that we saw, which surprised us, was the mountain still intact. The difference is, now it has a massive hole in the very, very top, nearly a kilometre deep.

When we put the cameras down, we just saw devastation — not a bit of life to be seen. This is the most biologically productive part of the planet and we were seeing hour after hour, kilometre after kilometre, of zero life.

How much actual material came out of the volcano?

We estimate about six cubic kilometres. That's a vast amount of material. When Mount Saint Helen's erupted in 1980, there was about one cubic kilometre of material.

This was six that went to the atmosphere, and then what goes up must come down, so that's six cubic kilometres that came crashing back through the water onto the sea floor. It then removed another four cubic kilometres of material.

So suddenly you now have 10 cubic kilometres of material mobilized. And as it moved through the water, it just smothered the ocean floor in every direction.

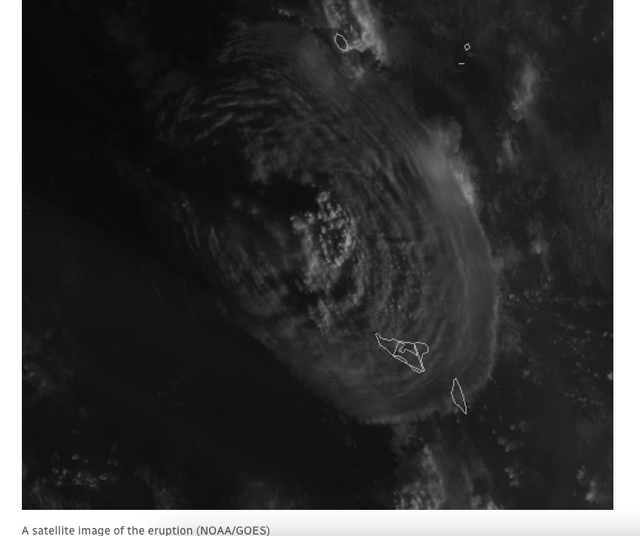

The eruption itself broke so many records about our understanding about science. When a very large volcano erupts, they usually have clouds that go up to about 25 kilometres high, and when the ash hits the bottom of the stratosphere, the jet stream streaks that material away and kind of wraps it around the world.

This particular eruption was so powerful, NASA actually detected the cloud rising to 57 kilometres high. That's twice as high as the previous known limit of a volcanic eruption. That meant that it had so much power, and so much velocity, it punched through the jet stream of the stratosphere and it pushed ash and basically salt water into the mesosphere.

NASA detected Pacific Ocean water in outer space. No one even thought it was even possible to do because of gravity.

[Do you find that interesting?]

What could have triggered this?

This sort of eruption would never happen on land. The atmosphere air is not dense enough to create that level of explosion.

This explosion can only happen in an underwater setting because when water meets magma, it instantaneously turns to steam.

And the steam will be 1,000 times the volume of what it was in water.

So you have cubic kilometres of ocean water hitting a magma chamber that flashes it instantaneously to 1,000 times its volume.

That's the bang!

This particular eruption is sort of like a "Goldilocks" eruption." If a volcano had been any shallower, there would not be enough volume of salt water to create that level of explosion. But if the volcano had been any deeper, then the water pressure would be too great to let that explosion happen. The water pressure would have suppressed that explosion.

Boy. So it was a steam explosion basically that gave it the violence, but what was the original trigger?

There was a pool of magma in the magma chamber that had been sitting there for about five years.

It had a fresh pulse of volatile rich magma that was pushed into the magma chamber. And this volatile, rich magma effectively [was like] shaking a champagne bottle.

And that's what drove that explosion.

There was an explosion that removed part of the lid of the magma chamber that let a little bit more water in.

That exploded.

That released a bit more the roof of the magma chamber to let more water in.

And it got into this chain reaction that each little eruption let a little bit more water in.

Eventually the whole magma chamber was exposed to all the sea water, and that was the bang.

Find more here,

Quirks and Quarks

Tonga volcano triggered record-breaking lightning and a never-before-seen tsunami

One of the most violent explosions in the South Pacific in centuries will be studied for years

The eruption of a large volcano in the South Pacific on January 15 has done significant damage to the island nation of Tonga. It also resulted in a number of exotic phenomena like super-intense lightning strikes and a rare "meteotsunami."

#TongaVolcano, #Tonga, #HungaTongaHungaHaapai, #Volcanoes, #UndergroundVolcanoes, #Magma, #SonicBoom, #underthesea, #Bang, #Volatile, #eruption

SOURCES:

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/quirks/record-smashing-tonga-volcano-1.7096003