Why discussing taste is more forbidden than sex or cash

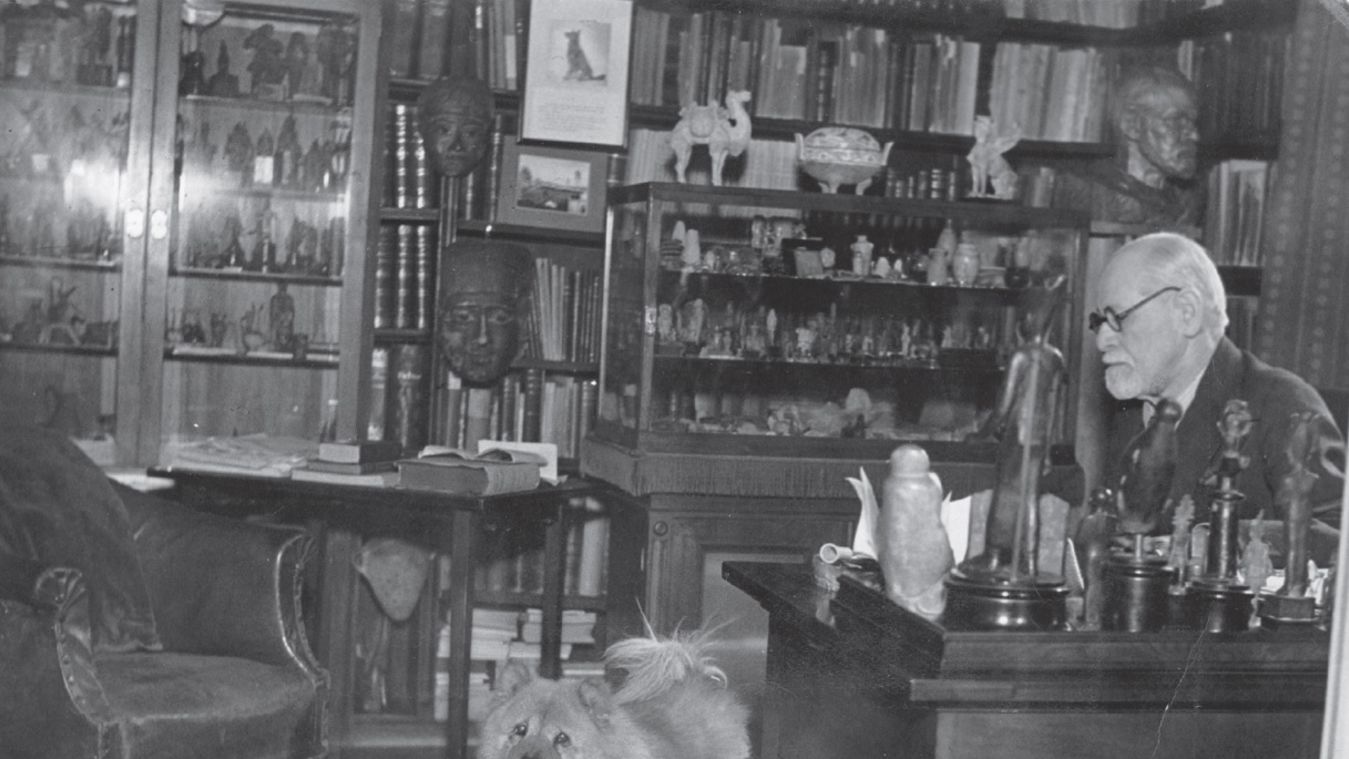

Look above at Dr Freud's counseling room. The colossal man is sitting in a solemn Viennese inside, presumably satisfied with the well known gathering of The Interpretation of Dreams. You can see the craquelure, notice the calfskin and the clean, sense the aspidistra, sniff the tidy.

Despite the fact that it is a highly contrasting photo, you can tell the predominant shading is dark colored. Tomes of horrid, insightful Mitteilungen recommend that analysis has the endorse of the past, that it is an antiquated and regarded scholarly restorative practice.

A few things would be unique if Dr Freud were rehearsing in New York or London today as opposed to in the unstable Vienna of Loos, Schiele, Klimt and Werfel.

One is that his counseling rooms would not appear to be identical: these days pioneers of the therapeutic calling don't present their reality regarding grave middle class inside outline. Rather, well off medicinal demonstrable skill is recommended by dark calfskin and chrome furniture, middlebrow garbage workmanship and glass tables heaped high with photograph monographs beside the water-cooler.

The other is that the dim corners of patients' psyches would, on assessment, be observed to be consumed not by Freud's own tensions about sex, passing and mother (for these days these things are ordinary), yet by ... taste. This word, which some time ago connoted close to "separation," was commandeered and its significance swelled by a powerful tip top who utilize the articulation 'great taste' essentially to approve their own stylish inclinations while exhibiting their profane assumption of social and social prevalence.

The general thought of good taste is guileful. While I hold back before trusting that every human issue are close to a wilderness of moral and social relativity, the recommendation that the boundless assortment and immense breadth of the brain ought to be constrained by some well mannered component of "good shape" is crazy.

Everybody has taste, yet it is to a greater extent an unthinkable than sex or cash. The explanation behind this is straightforward: guarantees about your dispositions to or accomplishments in the fleshly and budgetary fields can be debated just by your darling and your monetary guides, though by influencing proclamations about your taste you to uncover body and soul to loathsome open investigation. Taste is a brutal deceiver of social and social demeanors. In this manner, while anyone will let you know as much as (and maybe more than) you need to think about their triumphs in overnight boardinghouse the bank, it is taste that gets individuals' nerves shivering.

Nancy Mitford noted in her intense discourse of the expression "normal" (as in "He's a typical little man") that it is regular even to utilize "normal," which gives twofold bluffers rich chasing grounds among the ungainly and unreliable. Express social class, unequivocal material taste, social rivalry and social displaying are a piece of the post-mechanical re-requesting of the world and as Nick Furbank cleverly called attention to in his book about highbrow character, Unholy Pleasures (1985), "in classing somebody socially, one is at the same time classing oneself". He may very well as effectively have said "in censuring another person's taste, one is at the same time reprimanding oneself".

The one certain thing about taste is that it changes.

Taste started to be an issue when we lost the inclination for coherent normal magnificence controlled by the Neoplatonists and medieval craftsmen and authors. Nature and workmanship are, it could be said, alternate extremes, and craftsmanship has been the most dependable indicator of dispositions to excellence. As Andre Malraux noted toward the finish of the 1940s, in the cutting edge world, craftsmanship, even religious specialty of the past, is separated from its religious purposes and has turned into a debatable item for utilization by rich people or by exhibition halls.

Workmanship was the principal 'originator' stock and there is no surer exhibit of fluctuating taste than the notorieties of the colossal specialists and the photos they made. Found the middle value of crosswise over hundreds of years of first lionization and afterward disregard, unmistakably these notorieties have no lasting worth: the estimation of the estimation of craftsmanship depends as much on the social and social states of a specific watcher as on qualities encapsulated in the work itself.

We find in the past what we need to see. Business analysts call the impacts of this "survival predisposition", we call it taste. In the sixties Gaudi's design was rediscovered, in spite of the fact that it had never extremely left, since it had illusory qualities which the hallucinogenic age perceived. In the seventies, "Workmanship Deco" ended up noticeably settled as a respectable craftsmanship authentic name, despite the fact that Alfred H. Barr and Philip Johnson had prohibited it from the new Museum of Modern Art in New York on grounds of it being trivial and simply brightening.

At some point, obviously, the just improving is precisely what's required.