["My Life in Focus"] I. Living "La Dolce Vita"

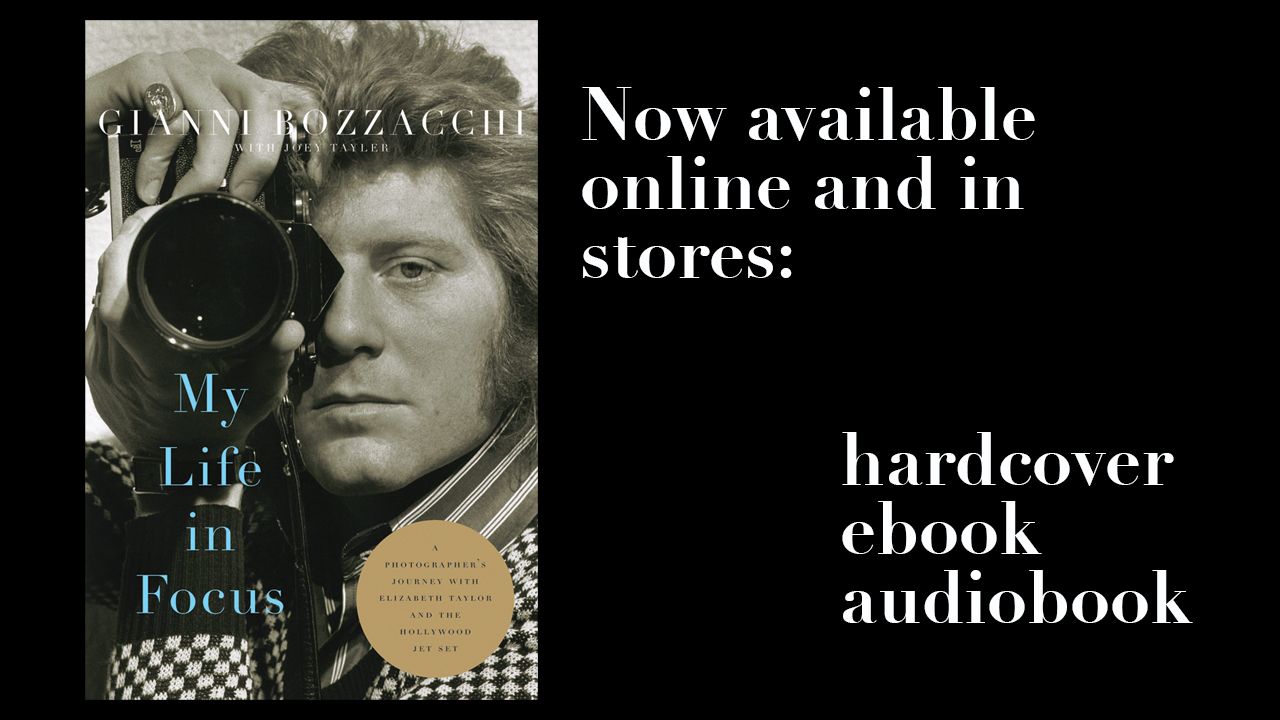

The following is an excerpt from Gianni Bozzacchi's autobiography, "My Life in Focus: A Photographer's Journey with Elizabeth Taylor and the Hollywood Jet Set," which I co-wrote.

An Introduction to the Life and Work of Gianni Bozzachi

I. Living “La Dolce Vita”

I’d watched Fellini shoot his masterpiece in 1959. Now, in 1963, it felt as if I’d punched a hole in the big screen and stepped right into the movie itself, wandering through the streets of the same glorious Rome anticipated by “La Dolce Vita.”

The epicenter of this Roman renaissance was Via Margutta, a street of artists just around the corner from Piazza di Spagna. Imagine the interminable concentration of Hollywood glamor offered by Sunset Boulevard, all compressed into just a few short blocks, and you’ll get an idea of what Via Margutta felt like in those days. It was the place to go to see Rome’s beautiful people, where to be seen in if you were one of them. Or – as in my case – were trying to be.

I read an article about the photographer Pierluigi Praturlon, who had a private studio in Rome and an international advertising agency. He’d been responsible for taking the set photos of “La Dolce Vita,” photos that had proved fundamental in promoting the wonders of Rome, Fellini and the movie itself, in America and abroad. In fact, the famous scene of Anita Ekberg in the Trevi Fountain was based on a photo that Pierluigi had taken himself, some years before the movie. That story goes that he and Ekberg had been walking back from a restaurant to Ekberg’s home when she stopped to bathe her aching feet in the fountain. Pierluigi quickly got a car owner to shine his headlights on the scene and, with that as lighting, took a series of photos. Fellini saw them in a magazine and used the idea in his movie.

I called Pierluigi’s office to ask if they needed anyone. They said they already had a lot of photographers, but needed someone who knew how to do retouching. They gave me a photo of Elizabeth Taylor to retouch. Nobody could tell where I’d intervened. When Pierluigi got back from Spain, he called, asked me to come in to see him and gave me the same photo of Elizabeth to retouch. He wanted to see if I was capable of doing it again. When I’d finished, he examined both retouched photos and couldn’t find any difference between them. “You’re hot shit,” he said, unable to believe I was so good so young. I got the job.

I’d begun as a retoucher, but slowly began taking photos. Pierluigi worked for a lot of production companies: MGM, Paramount, Warner Bros. He handled photo shoots and layouts for big stars. He wasn’t managing a mere photography studio, but a major enterprise with as many as ten apprentice photographers working under him, plus correspondents in major cities throughout the world, just like a newspaper. But whoever bought celebrity magazines, or 18x24 photos of stars, never heard anyone talk about other photographers – guys like me – because the only name to appear on photos coming out of Pierluigi’s studio was Pierluigi’s. He took all the credit and the copyrights, regardless of who’d taken the photo.

One day Audrey Hepburn came into the studio for a shoot. She was a little early, and Pierluigi was busy on the phone. I set up the lights while she went to the dressing room with Alberto De Rossi. When she finally got on set, Pierluigi was still on the phone. She was dazzlingly beautiful and elegant and, given my sketchy English, I was too intimidated to strike up a conversation. So, instead of standing there like a mute, I started photographing her. I must have given the impression of being a professional photographer because, when I stopped, she hugged me goodbye and left, just as Pierluigi came into the room. He was furious. Until he saw the prints.

(Copyright Gianni Bozzacchi)

That photos I took of Audrey became so famous it was printed and sold as a poster. Pierluigi signed it, just like all the others.

The incident with Audrey made me realize just how jealous Pierluigi was, and how distrustful he was of his collaborators. I got the impression that he kept an even closer eye on me after that, like he was trying to catch me stealing something.

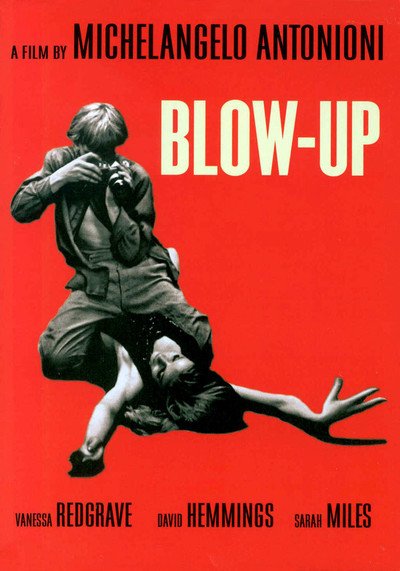

Not long after, I was busy photographing one of the many models and actresses who constantly hung around the studio, each hoping to get into a shot that might end up in a commercial, or get movie work. For this particular shoot, I had the girl stretch out on the floor while I stood taking photos of her from above. I then got down on my knees, straddling her, while I kept shooting. I liked the sexual tension that developed between a subject and myself. It was a technique I used often throughout my career, sometimes clothed, sometimes not. Pierluigi was standing off to one side with a man I didn’t know, who watching me closely. From the way Pierluigi was talking to the guy, I could tell he was someone important. When I was through with the shoot, Pierluigi called me over and introduced me. Michelangelo Antonioni. From the expression on Pierluigi’s face, it seemed I’d done something wrong. I figured I was in trouble. When Antonioni asked if I’d like to go to London to work on his next movie, “Blow-Up,” I realized why Pierluigi was so put out. It was possibly the first time someone had come to his studio and asked for one of his employees. It wouldn’t be the last.

Michelangelo didn’t want me to take photos, but to work with the star of the movie, David Hemmings. My job, in secret, was to teach him my “body language.” I showed David how to hold a camera, how I’d move in order to get the right angle, how and why I made models lie on the floor. Michelangelo liked the angle so much he got Hemmings to repeat it with the model Veruschka. In the scene, while Hemmings is photographing Veruschka, his shutter starts opening faster and faster, in time with her growing excitement, until in the end she almost seems to have an orgasm. The scene, however, is as emotionally empty as it’s sexually charged. Hemmings and Veruschka are on top of one another, but couldn’t be farther apart, which was Michelangelo’s genius: his portrayal of the sad poetry that he sensed within our inability to relate to others.

On my return from London, Pierluigi figured he’d concocted the perfect punishment for me. I was to be sent to Dahomey (Benin), where Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton were filming “The Comedians.” Nobody in the studio wanted to go to Africa, me included. But Pierluigi persuaded me that it would be good experience. He said I’d handle every aspect of the job: I’d photograph Elizabeth and Richard, co-stars Alec Guinness, Peter Ustinov, and James Earl Jones, and retouch and print all the photos on location.

So, at the end of November 1966, I packed a full darkroom kit, and flew to Paris, along with one of Pierluigi’s printers, Franco. I didn’t know how, when I eventually returned to Rome, Pierluigi would have even more reason to get annoyed. And how I would then soar clear out of my basement life forever.

Come back on Friday for Part II, in which Gianni shoots unauthorized photos of Elizabeth Taylor and nearly shoots Marlon Brando with a gun. For real.