Illegal: a true story of love, revolution and crossing borders [Ch.25]

I'm a journalist for publications such as The Guardian, Vice, The Diplomat and Narratively and my first book, a memoir, came out just over a year ago [Amazon link]. It's won numerous awards and sold thousands of copies. And now I want to give it away. This is the twenty-sixth installment [Prologue | Ch 1 | Ch 2 | Ch 3 | Ch 4 | Ch 5 | Ch 6 | Ch 7 | Ch 8 | Ch 9 | Ch 10 | Ch 11 | Ch 12 | Ch 13 | Ch 14 | Ch 15 | Ch 16 | Ch 17 | Ch 18 | Ch 19 | Ch 20 | Ch 21 | Ch 22 | Ch 23 | Ch 24] and every few days I'll post another chapter. From the back cover:

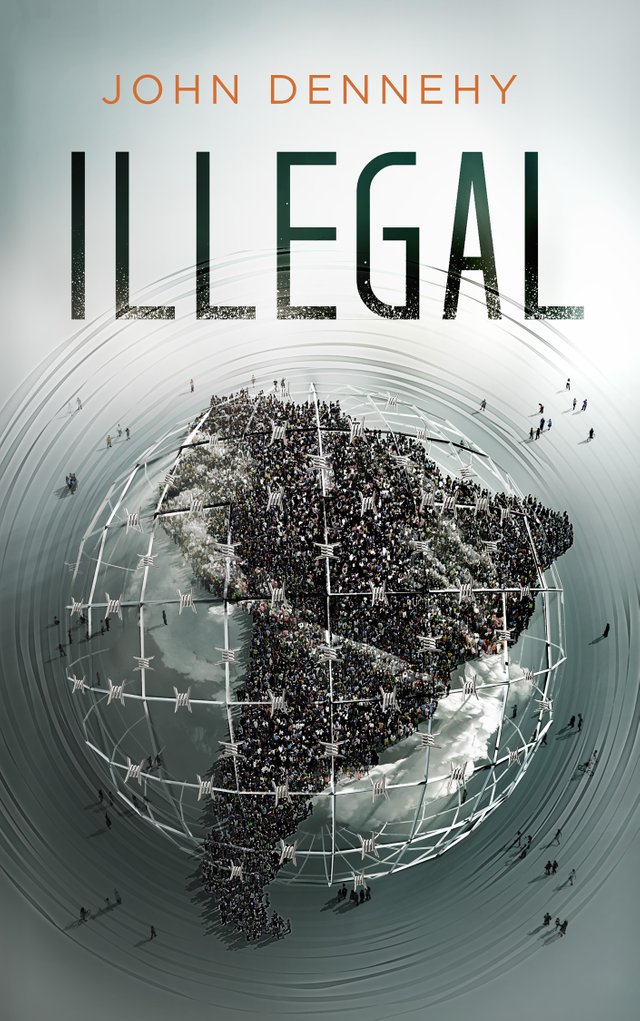

A raw account of a young American abroad grasping for meaning, this pulsating story of violent protests, illegal border crossings and loss of innocence raises questions about the futility of borders and the irresistible power of nationalism.

--

The Agony of Borders (2) [Chapter Twenty-Five]

Lucía woke me up from a nightmare at 6:40 a.m. We were already behind schedule. It was the 25th of January and my Colombian visa was set to expire the following day. I wanted to be at the border by lunch; and Lucía was late for work. I started getting ready as quickly as I could. Our shower was broken, so I used the one downstairs. Normally I would just skip it, but before setting off on a trip of this nature, where anything seems possible, it’s good to be clean. Our landlord yelled at me for using his shower, then I returned to our apartment and Lucía yelled at me because she was going to be late for work. The day was off to a rough start.

Lucía and I had done our best to recover from the terrible fight we had before my deportation, but it was a bumpy road. A couple of weeks earlier we had been out drinking and got into another fight. This time it was because a woman asked me to dance twice—I declined both times but that was enough of a spark. Lucía stormed off, taking my keys, and I followed a minute behind. She locked the door, laid down on the floor of our living room and cut her wrists, all of which I could see through the window. I tiptoed on a ledge that ran alongside the house and climbed into our open bedroom window. We quickly made up, but the next day I broke a little bit. The veneer of my fantasy began to crack.

I wasn’t the first person she had dated after her marriage; she had also had an affair with a man from Argentina. That relationship never got very serious but she told me she thought about suicide when that ended.

“You need to call your mom,” I told her. “You need to tell her everything.”

“No.”

“Baby, I love you, but I can’t do this anymore.”

“What are you talking about?”

“You really scared me last night. I don’t want anything bad to happen to you.”

“I was fine.”

“You need to have someone to talk to when you’re angry with me. I need help, baby. I need this. Please. For me?”

Looking back, that was probably the beginning of the end. It was the first time I ever had even an inkling of a thought that I wasn’t helping Lucía. It was the first time I wanted someone else to step in.

As Lucía and I headed to the bus station, walking silently and standing apart, I was thinking about hitmen hunting me down and Lucía bleeding from her wrists. I was not okay. Somewhere along the way I began to lose my patience and ability to always see the bright side of things. Part of me wanted to blame Lucía because it’s easier to not take responsibility, but honestly I was more prone to fighting and less likely to forgive than I had been just a few months before. I was trying to cope with a lot; and so was she.

We boarded a bus for Lasso, the small industrial town on the way to Quito where Lucía had recently started an unpaid internship.

“I’m sorry baby, I just hate these trips,” I told her.

“I know. And I’m still upset with Veronica. I’m sorry too,” she said.

That week Lucía had interviewed for a high-paying job and was told that the position was hers pending approval from the company board. After hearing her good news, Veronica used a family contact to land the job for herself instead.

“She is a dog,” I said. And we both laughed. Calling her a perra, a dog, was a strong insult and had become my unofficial nickname for Veronica since she and Lucía had their falling out.

Just as I had deflected all the blame away from Lucía and toward her husband, we had collectively begun to blame Veronica for further troubles. Sure, some of that ire was deserved, but in hindsight it seems clear that we were also avoiding taking responsibility for ourselves. It would eventually all catch up to us.

While the bus sped away from Latacunga, Lucía leaned against me and buried her head into my shoulder. I moved my hand across her body and over her shoulder and squeezed into a hug, then left my arm draped over her. We kissed as she got off at the rose plantation where she was interning; and I was alone.

I got off a few minutes later and transferred to a new bus headed to Quito. Every few minutes the bus would slow down just enough to allow someone to jump on or off, occasionally coming to a full stop for larger groups or for farmers transporting sacks of food to some distant marketplace. The sacks were quickly thrown into the bus, or more often, thrown on top of it. A young man carrying a chicken upside down by its tied feet sat down next to me, and the bus began to fill. As we approached the modern capital, the stops became more frequent, and university students, backpacks slung over their shoulder, stood in the aisle as the empty seats disappeared. Once into the sprawl that stretched endlessly south from the city’s center, new vendors jumped on each time the bus slowed. Over the drone of the diesel engine and conversation they squeezed themselves through the crowded aisle and back again, calling out whatever product they happened to be selling. When I heard the familiar cry of “¡Papas!¡Papas!” I bought my meager breakfast in exchange for fifty cents.

By now this scene was familiar, but when I first arrived in South America, both the chaos and extreme utility of the region’s buses had amazed me. Shortly after I finished my oversized bag of homemade potato chips the bus pulled into the capital’s main bus station. Amid hundreds of these old machines that kept the country moving, I tried to plan my return from the border and asked around when buses would stop running to Latacunga that night. Whenever asking for a bus schedule, directions or anything of that nature, everyone had their own answer, so it was best to get a few opinions and take the average. With this method I had a vague idea that buses would stop at eleven or twelve and start again around four or five. Satisfied, I gave a small girl ten cents in exchange for a wad of cheap toilet paper and use of the dirty public bathroom she sat in front of. Unless it was an emergency, I avoided doing anything that would necessitate the use of that complimentary, but always insufficient, wad of paper. Plumbing was not one of the nation’s strong points and flushing usually meant dipping a bucket into some giant container of dirty water. Even with the soiled paper thrown into its own bucket in the stall, the toilets were still prone to clogging. Sometimes there were urinals, and other times just a trough, but either way, taking a piss seemed far more sanitary.

With my bladder emptied I was ready for a long and uncertain bus journey. I walked back onto the road where I knew I could hop onto a bus heading north. About halfway there, in the city of Ibarra, for a reason that was never explained, we were all made to switch buses. That is where my real journey began. The other side of Ibarra was where the police checkpoints were located and the dangers of my situation were exposed.

All week I had traded sleep for anxiety, lying in bed thinking of stories I could tell and roles I could play if questioned by police. This was undoubtedly the cause of the nightmares that haunted me when I was able to drift into an awkward unconsciousness. Each day I devised new plans and held them against the older ones. On the bus, I put them all together and debated, in long drawn-out internal dialogue, which story I would use.

Most versions of the character I played were not able to speak Spanish, and I had to keep that consistent. The bus rides were solitary adventures where I had nowhere to turn but inside, so I poured over my recent life and the dangers I was in. I lost my mind but kept a dumb smile on my face.

We all wear masks, but if you wear the same one for too long for too many people, it can begin to consume the face behind it. Somewhere in the last few months I had forgotten who I was.

It was difficult to dig myself out of the financial hole I found myself in after my deportation—more difficult than I thought it would have been. Besides the occasional work in Ana’s shop, la Señora took me on long bus rides toward the Amazon where we would pick orchids and other flowers to sell in Latacunga.

The ‘tutoring’ work Kleaber helped me find quickly mutated into something far less noble: I began just doing students homework, which paid better. Not long before, I would have considered this work immoral, but after a while I barely hesitated when new clients came my way. In a short time, I went from someone who helped others learn to someone who helped them cheat. I also made deals with local travel agencies to steer clients their way and started selling marijuana to these same tourists. I gradually reduced my volunteering at INNFA until I stopped going altogether to have more time to make money in whatever way I could. But it wasn’t just about freeing time. In the beginning at INNFA I tried my best to be understanding and kind, someone the children might learn from, and I didn’t want them to see what I was turning into.

I stopped doing what I believed in and replaced that void with things that made me feel guilty and wicked. I did whatever I could to keep the dream alive. I was paranoid, scared and desperate, and somehow, amidst that, I reasoned that the best way to get back to the values that had made my life so fulfilling was to completely abandon them.

I hated it. I hated all of it, but I told myself it was necessary and only temporary.

As a journalist you must be use to having to promote your work. I see you are buying votes for your posts, but it doesn't seem to get you many comments. Is that what you want? I've no idea if you make profit this way. Do you comment much on other posts? I've found that's the best way to gain engaged followers. Steemit has some good community, but you have to go and find it. There are lots of writers here who would appreciate some feedback.

You may be right. I don't comment much at all on other posts and I'm sure that would be very helpful. I actually try to severely limit my time on any social media, though I'm also a huge advocate of crypto. I do appreciate good writing though so I think I may take your advice. Cheers!

You may find that just being on Trending doesn't get the best engagement as a lot of people don't look at it. Quality can be found elsewhere generally :)

Cheers!

This Advise Is Quite Necessary; but I Think Some Folk Indulge In This Because It Could Be Very Demoralizing To Notice That None or Few Appreciated Your Well Thought Out Content.Nevertheless, Engagement By Comment Interactions Would Level Off This Phobia As Others Would React By Upvote Or Comment Appreciation.

Nice book! Happy to read

Thanks!

Extraordinary story & good writing!!!

Emmm interesting 😏

Posted using Partiko Android

Hello, I read your book is very interesting. Greetings

Your efforts in creating this blog are clearly visible. keep the amazing work on.

Cheers!

I'll be reading and upoting what I can. It's the big disadvantage of this platform that older stuff doesn't get benefits for the author.

Cheers! I love gardening and sustainable living so I'll be following you as well now.

This book is great! Since I recieved it via email from you I'm reading it every day chapter by chapter! Thank you for this book!

happy to hear!

a lot of talent...

Cheers!

You got a 62.62% upvote from @upmewhale courtesy of @johndennehy!

Earn 100% earning payout by delegating SP to @upmewhale. Visit http://www.upmewhale.com for details!