Illegal: a true story of love, revolution and crossing borders [Ch.34]

I'm a journalist for publications such as The Guardian, Vice, The Diplomat and Narratively and my first book, a memoir, came out just over a year ago [Amazon link]. It's won numerous awards and sold thousands of copies. And now I want to give it away. This is the thirtieth installment [Prologue | Ch 1 | Ch 2 | Ch 3 | Ch 4 | Ch 5 | Ch 6 | Ch 7 | Ch 8 | Ch 9 | Ch 10 | Ch 11 | Ch 12 | Ch 13 | Ch 14 | Ch 15 | Ch 16 | Ch 17 | Ch 18 | Ch 19 | Ch 20 | Ch 21 | Ch 22 | Ch 23 | Ch 24 | Ch 25 | Ch 26 | Ch 27 | Ch 28 | Ch 29 | Ch 30 | Ch 31 | Ch 32 | Ch 33] and every few days I'll post another chapter. From the back cover:

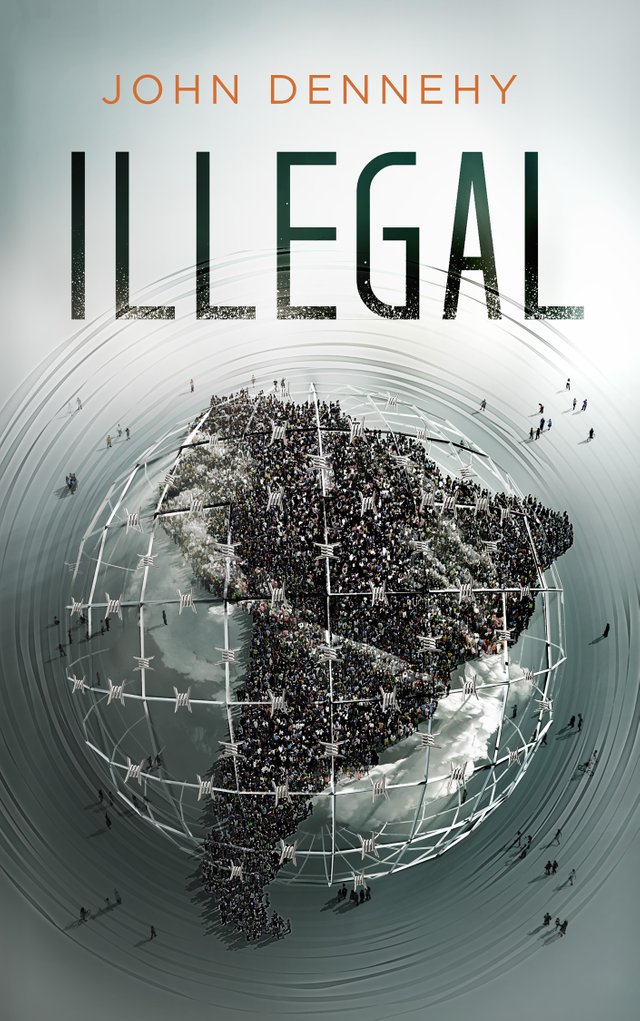

A raw account of a young American abroad grasping for meaning, this pulsating story of violent protests, illegal border crossings and loss of innocence raises questions about the futility of borders and the irresistible power of nationalism.

--

Epilogue: Ecuador 2017 (3) [Chapter Thirty-Four]

After a week with Ana I found a new place to live at the northern edge of the city. Next door iron rebar rises out of cement columns and reaches toward the sky. There is a cement foundation beneath the columns but nothing more; the house was abandoned amid its construction. Across the street is a massive vacant lot of overgrown grass and weeds. Cows munch on the grass and feral dogs patrol the edges. In one lot, the owners built a wall around their property and then abandoned the project, so now their lot of weeds and grass is more exclusive than the rest. Behind my small house concrete boxes are stacked on top of each other on what would have been a two-story building. There are no windows or doors, just holes in the grey concrete.

This neighborhood was abandoned after Cotopaxi erupted in 2015. It is now considered a ‘Risk Zone’ and no new construction is allowed, though even if it were it’s doubtful many would want to live here. My house is one of a handful that were completed before the construction freeze. The eruption, the first in over 100 years, was a surprise but was also minor—little more than a puff of steam and some ash. However, it signaled that the ‘throat of fire’ is likely gearing up for a major event, the kind that will probably destroy Latacunga. My current neighborhood, Campo Verde—Green Country, will be the first to go. It’s located at the northern edge of Latacunga, facing Cotopaxi and on the banks of Río Cutuchi.

Inside the city center there are blue signs with arrows on nearly every street pointing toward ‘Evacuation Routes.’ Inside all the parks there are maps of the city and lists of neighborhoods that are considered risk zones. Large maps of the city have been printed out and taped to walls inside pharmacies and restaurants. The predicted path of mud flows—the flow that will be created when the ice cap melts and the flash flood mixes with ash and gravel to form a tidal wave of wet cement barreling down the valley carved by Río Cutuchi, the valley Latacunga is built in—is colored red. Almost the entire city is colored red.

The Pan-American highway, once just one lane in each direction, is now up to three. And another brand-new highway, sometimes as much as four lanes in each direction, has been built parallel to it. Surprisingly, this has not reduced traffic. Just as the government has taken out large loans, so have Ecuador’s citizens. Personal debt, once rare here, has ballooned and much of that newfound, if illusionary, wealth has gone into automobiles. The new roads avoid population centers. The buses no longer give you a glimpse of each town as you roll through it and fewer vendors come onboard to sell their wares.

The beautifully chaotic market I saw that first day in Latacunga, El Salto, has been covered over and replaced by a three-story concrete structure where vendors must rent small stores from the government. A metal gate closes off each tiny box when the vendor goes home at night. It looks and feels like a strip mall. Since I arrived that first day in 2005 the city has moved away from the open-air markets that filled all the plazas and dominated commerce. Chain supermarkets have sprouted around the city. And just across the highway from El Salto, across one of the dozen new or expanded bridges the government has built over Río Cutuchi, is Latacunga’s first mall. It looks exactly like all the malls I grew up with on Long Island.

I came here twelve years ago when the nation was on the cusp of dramatic change, and it seems I am witnessing the death of that era now. After a decade of growth, the economy, heavily dependent on exporting oil and now burdened by paying back a decade of debt, is contracting.

My perspective is also vastly different. Young and naïve, I idealized la Revolución Ciudadana at its birth. When it didn’t meet my, probably always unrealistic, expectations I became bitter in my disappointment. For a while I think that bitterness made me swing too far in the other direction. I’d like to think that I’ve since found a balance between those two extremes, and while recognizing that some positive things have happened, I still oppose Correa and his government based on repressive policies directed toward the press and social movements, two areas of particular concern to me. Though, surely some of that bias of my personal experience of wild hope then crushing disappointment still exists and informs my view.

Rafael Correa, once one of the world’s most popular presidents and still a darling of many in the U.S. left, is now hated as a dictator not just by me but also by nearly half the nation of Ecuador. In the ten years preceding Correa, Ecuador had seven presidents. The constitution stated that no president could serve consecutive terms, which are four years each, though most were overthrown long before that. Yet, Correa ruled the nation for over ten years—an impressive feat. He twice rewrote the constitution and dramatically shifted power toward the executive branch while also growing the government. When protests broke out after he announced he would allow indefinite reelection he compromised by having the change take effect after the 2017 election which he would sit out.

Lenín Moreno, the ruling party candidate and Correa’s former vice president, won a narrow victory, 51% to 49%. However, some early exit polls showed a victory for the opposition candidate, Guillermo Lasso, which fueled claims of fraud.

Here in Latacunga, police broke up crowds with tear gas. In what was a dramatically close election, the government lost Latacunga in a landslide: 61% to 39%. Few people I know who voted for Lasso liked him; most were voting against the government. Latacunga, one of the nation’s radical centers, had been one of Correa’s strongest bases when his government began, but the city has slowly transformed into a center of resistance against his government.

Correa has been mostly successful in co-opting or crushing the social movements that elected him but UTC has become notable for being the only university in the nation that resisted co-option by la Revolución Ciudadana for Correa’s entire term. MPD, that small Marxist party that was the only recognized party to support Correa during his first campaign, has become his bitter rival and still holds onto power at UTC.

The election protests fizzled out after a week. The spirit of resistance, the idea that the people could overpower their own government when it stopped serving their interests, is gone. The irony is that Correa, the firebrand anti-American populist, has transformed Ecuador into a place that resembles my own nation more than anyone else ever has—from malls and consumerism to political apathy and fear.

When Ana and I visited the highway blockade north of Latacunga in 2006, the one that sparked a nationwide revolt and put Correa in the spotlight as a champion of the social movements, I had never felt so inspired. In that exact spot, the government has built a mega jail which now holds five thousand prisoners.

--

visit http://illegalbook.com/

I hope you can write more wonderful articles.

Thanks! Glad you enjoyed it.

Saludos @johndennehy, excelente capítulo, trata sobre los problemas superados de infraestructura, así cómo los problemas politicos qué se desarrollan en los países latinos, en estos capítulos planteas un análisis social del "dónde venimos y, a donde vamos como pueblo latino "

Gracias! me alegra que te gusta

looking forward for the next chapter.

thanks!

I enjoyed reading your article . hoping to see more of your works.

The next (and last for this book) chapter should be up in another day or two.

looking forward to the next chapter! share more of your talent in your future artices.. please.

Thanks! I will!

oh my! have to read back.. have not been so active lately..

:)

Gteat words thank you

Thank you!

is it ok to print this for my personal reading? i am just more comfortable that way.

true.. it's more convenient. it will be great if the pages are bound. happy reading!

I agree. I'm old-school and prefer paper as well. It's also on sale in paperback on Amazon (or for crypto from me).

of course! enjoy.

wonderful! thank you!

what I know about Correa, is very developed for now, maybe your trip a few years ago, it looks a lot of changes compared to now

well, it's a controversial topic. I think everyone would agree that Ecuador is more 'developed' now in the sense of more roads, bridges, etc. I don't like the other stuff and am wary of other things like increased personal and national debt, but much of that can be a matter of perspective or opinion. When were you there? Where did you go?

This is the penultimate chapter. The next chapter [35] will be the last. Thanks for joining me! Hope you've enjoyed.